The Council of Nicæa, as church historians well know, was convened to address the errors of Arianism. Early in the 4th century, Alexander of Alexandria, sent a letter to Constantinople warning of the spreading error (Alexander of Alexandria, To Alexander, Bishop of the City of Constantinople, paragraph 1 (320 A.D.)). Within four years the dispute had captured the attention of the emperor, who sent his emissary, Bishop Hosius of Cordoba, to Alexandria to lend his prestige to the resolution of the matter (Socrates Scholasticus, Ecclesiastical History, Book I, Chapter 7). Finally, in 325 A.D., a general council was convened in Nicæa to address the matter and put it to rest. Because of its significance to the doctrinal health of the church, the Arian heresy typically receives first billing whenever the Council of Nicæa is described. But there was another significant matter, another dispute, that threatened the administrative health of the church. The way that dispute was addressed at Nicæa puzzled Patristic writers and church historians for the next twelve hundred years and led to one of the most pervasive myths in the history of ecclesiology. That dispute was the matter of Metropolitan jurisdiction and the boundaries within which a Metropolitan bishop was authorized to act. The myth that resulted from Nicæa’s solution was the false belief that the Council had acknowledged the primacy of the Bishop of Rome.

The canon in question is the 6th which reads as follows:

“The ancient customs (εθη ) of Egypt, Libya and Pentapolis shall be maintained, according to which the bishop of Alexandria has authority over all these places since a similar custom (συνηθες) exists with reference to the bishop of Rome. Similarly in Antioch and the other provinces the prerogatives of the churches are to be preserved…” (Council of Nicæa, Canon 6 (325 A.D.))

We hasten to point out that the original canon used two different words for what we now render in English as “custom.” The former term, εθη, refers to something that is authoritative for its antiquity, whereas the latter term, συνηθες, refers to something that is currently practiced, and has lately become ordinary. The appeal to the Roman custom, συνηθες, therefore was not an appeal to antiquity, but to a recent development in Rome. There was a recent practice “with reference to the Bishop of Rome” that informed Nicæa’s solution regarding Alexandria’s ancient Metropolitan authority. But what was that recent practice? What was that “similar custom”?

Roman Catholics insist that the “similar custom” was the “ancient” understanding of Roman Primacy. A typical Roman Catholic interpretation of the 6th of Nicæa reads as follows:

“Let the Bishop of Alexandria continue to govern Egypt, Libya, and Pentapolis, since assigning this jurisdiction is an ancient custom established by the Bishop of Rome and reiterated now by this Nicene Council.” (Nicæa Canon 6 according to lay apologetics ministry, Unam Sanctam Catholicam, Papal Primacy in the First Councils)

When understood this way, “all of the sudden, this Canon has some ‘teeth,'” they say. “The appeal of the Council is to an ancient custom, which surely must have originated on some solid basis …, and this basis is none other than the delegation of the Bishop of Rome” (Unam Sanctam Catholicam, Papal Primacy in the First Councils). Thus, in the mind of the Roman Catholic, the canon is plainly a matter of the antiquity of Roman Primacy.

Of course, in the absence of any historical context—civil or ecclesiastical—such a reading may be plausible, although the two different Greek terms for “custom” in the original do not lend themselves to that interpretation. In any case, we do not have the luxury or the prerogative of simply extracting Nicæa from its historical context. Such extractions provide a notoriously unreliable basis for understanding history, and that is certainly the case here. An examination of the civil and ecclesiastical context of Canon 6 actually yields the very opposite of Roman Catholic claims. What was being “reiterated now by this Nicene Council,” was the fact that the jurisdiction of the bishop of Rome was quite limited indeed.

The Ecclesiastical Context

Leading up to the Council of Nicæa, one Meletius of Lycopolis had presumed to ordain bishops outside of his jurisdiction, causing no small scandal within the church. What he had done was contrary to the norms that had been established and honored in the Church for centuries. Upon receiving the news of his intrusion, bishops Hesychius, Pachomius, Theodorus, and Phileas wrote to Meletius of Lycopolis (c. 307 A.D.) to inquire after his unlawful behavior, and importantly, “to prove your practice wrong”:

“Some reports having reached us concerning thee, which, on the testimony of certain individuals who came to us, spake of certain things foreign to divine order and ecclesiastical rule which are being attempted, yea, rather which are being done by thee … . [W]hat agitation and sadness have been caused to us all in common and to each of us individually by (the report of) the ordination carried through by thee in parishes having no manner of connection with thee, we are unable sufficiently to express. We have not delayed, however, by a short statement to prove your practice wrong.” (Epistle of Hesychius, Pachomius, Theodorus, and Phileas, to Meletius).

As the four continued to explain, “it is not lawful for any bishop to celebrate ordinations in other parishes than his own.” What was worse, all of this had taken place while bishop Peter I of Alexandria occupied the Metropolitan seat. Meletius’ actions could hardly be understood in any other way than malicious ambition. “[L]ooking with an evil eye on the episcopal authority of the blessed Peter,” Meletius had threatened and undermined the authority of the Metropolitan, and these four bishops could not stand by and watch it happen.

The significance of this issue to the church may be understood from the Synodical Letter to Alexandria immediately after the council of Nicæa. The matter of Arius had been resolved, of course, but so too had the matter of “the presumption of Meletius” who had ordained bishops in the Metropolitan’s province:

“But since, when the grace of God had freed Egypt from this evil and blasphemous opinion, and from the persons who had dared to create a schism and a separation in a people which up to now had lived in peace, there remained the question of the presumption of Meletius and the men whom he had ordained, we shall explain to you, beloved brethren, the synod’s decisions on this subject too.” (Synodical Letter of the Council of Nicæa, To the Egyptians)

Thus, Nicæa had been convened to address two controversies of relevance to Egypt, one of which was the matter of Metropolitan jurisdiction. Canon 6 of Nicæa is explicit when addressing this matter. After defining the jurisdictional boundaries of the Metropolitan bishops of Alexandria and Antioch, the council continued, emphasizing that extra-provincial episcopal ordinations would not be recognized: “In general the following principle is evident: if anyone is made bishop without the consent of the metropolitan, this great synod determines that such a one shall not be a bishop” (Council of Nicæa, Canon 6).

The importance of this jurisdictional issue is plainly evident not only from the context of Canon 6, but from the canons of the subsequent councils. The Council of Sardica (343 A.D.) restated the policy, namely that the bishop of one diocese may not “ordain to any order the minister of another from another diocese without the consent of his own bishop” (Council of Sardica, Canon 15).

The Council of Constantinople (381 A.D.) restated the policy that “Diocesan bishops are not to intrude in churches beyond their own boundaries nor are they to confuse the churches: but in accordance with the canons, the bishop of Alexandria is to administer affairs in Egypt only.” (Council of Constantinople, Canon 2)

The Council of Ephesus (431 A.D.) restated the policy again, insisting that the bishop of one diocese was not to take possession of another man’s territory: “The same principle will be observed for other dioceses and provinces everywhere. None of the reverent bishops is to take possession of another province which has not been under his authority from the first or under that of his predecessors” (Council of Ephesus).

The matter of Metropolitan jurisdiction arose again at the Council of Chalcedon (451 A.D.). Canonically prohibited from aspiring to another man’s Metropolitan seat, some bishops were appealing to the civil authorities to create a new civil province, and with it, a new Metropolitan seat. But this practice was creating the problem of two separate civil provinces—and therefore two Metropolitan seats—within a single ecclesiastical province:

“It has come to our notice that, contrary to the ecclesiastical regulations, some have made approaches to the civil authorities and have divided one province into two by official mandate, with the result that there are two metropolitans in the same province.” (Council of Chalcedon, Canon 12)

Thus, from the Meletian schism in 307 A.D. to the Council of Chalcedon in 451 A.D., the matter of Metropolitan jurisdiction was at the forefront of conciliar polity, and Nicæa was always considered to be the authoritative standard. Nicæa had taken up the matter of Meletius’ presumptuous intrusion into a Metropolitan’s jurisdiction, and every council after Nicæa referred back to the way Nicæa had handled it. The issue of Metropolitan jurisdiction from Nicæa onward was nothing other than this: how shall we manage ecclesiastical boundaries when there are two or more Metropolitan bishops located within a single geographical unit?

What makes the matter problematic—and to some degree puzzling from an historiographical perspective—is that the very concept of a civil geographical unit itself was changing at the time of Meletius’ incursion. The Meletian schism occurred shortly after Emperor Diocletian had reorganized the Empire into civil dioceses, but before the church had formally begun to define ecclesiastical boundaries in diocesan terms. Eventually, the civil diocese would enter the conciliar vocabulary of the church. But not at Nicæa. Nevertheless, the council was keenly aware of Diocletian’s recent reorganization, as well as the new geographical unit—the diocese—that he had created. The history of Metropolitan jurisdiction and the meaning of Canon 6 of Nicæa, therefore, cannot be understood without considering the history of how the church adapted to the new term.

The Civil Context

Before the church adapted to Diocletian’s civil reforms, a bishop’s jurisdiction was described in provincial rather than diocesan terms. Thus the jurisdiction of the Metropolitan of Alexandria was defined at Nicæa by the civil provinces of Egypt, Libya and the Pentapolis. We might well ask why Nicæa did not simply accept the diocesan division of the empire and align the jurisdiction of the Metropolitans accordingly. Would that not have been a more practical solution? After all, it had been 32 years since Diocletian’s reorganization. Would it not have been simpler to accept the diocesan division of the empire and let each Metropolitan bishop preside over his own diocese? The answer to the question is as simple as it is obvious.

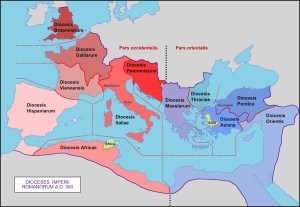

When Diocletian reorganized the empire, he created the Diocese of the East (the Diocese of Oriens), which spanned all the territory from Libya to Syria, as can be seen in the map at the head of this article. The Diocese of Oriens included within it the Metropolitan Sees of Alexandria, Jerusalem and Antioch. If the bishops assembled at Nicæa had aligned ecclesiastical boundaries to make them coterminous with the civil dioceses, they would have merely perpetuated the very problem they were trying to solve: the problem of multiple Metropolitans within a single geographical unit. Thus, the jurisdiction of the Metropolitans of Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem had to be defined in provincial rather than diocesan terms, and that is exactly what Nicæa did:

“The ancient customs of Egypt, Libya and Pentapolis shall be maintained, according to which the bishop of Alexandria has authority over all these places … Similarly in Antioch and the other provinces the prerogatives of the churches are to be preserved. … the bishop of Ælia [Jerusalem] is to be honoured, let him be granted everything consequent upon this honour, saving the dignity proper to the metropolitan.” (Council of Nicæa, Canons 6 & 7).

Notably absent from Nicæa is any mention of the civil diocese as an ecclesiastical unit. It simply was not an option.

Over the course of the fourth century, however, a partial solution presented itself, and when it did, the jurisdiction of Alexandria suddenly began to be described in diocesan rather than provincial terms. Sometime between the councils of Nicæa in 325 A.D. and Constantinople in 381 A.D., the Diocese of Oriens was split into two civil dioceses—the Diocese of the East, which encompassed Syria and Palestine, and the Diocese of Egypt, which encompassed the provinces previously assigned to Alexandria. It is at the council of Constantinople that we first begin to see the Diocese of Oriens distinguished from the Diocese of Egypt, both in the canons and in the Synodical Letter.

In canon 2, the provincial language of Nicæa was abandoned, and the jurisdiction of the Metropolitan of Alexandria was defined in terms of the Diocese of Egypt, which by then was a self-standing diocese in its own right. Likewise, the jurisdiction of the bishop of Antioch was defined in terms of the Diocese of the East:

“Diocesan bishops are not to intrude in churches beyond their own boundaries nor are they to confuse the churches: but in accordance with the canons, the bishop of Alexandria is to administer affairs in [the Diocese of] Egypt only; the bishops of [the Diocese of] the East are to manage the East alone (whilst safeguarding the privileges granted to the church of the Antiochenes in the Nicene canons).” (Council of Constantinople, Canon 2)

This was progress. Alexandria was now the Metropolitan See of the Diocese of Egypt, and the provincial terms of its jurisdiction could be discarded; and Antioch was the Metropolitan See of the Diocese of Oriens which now excluded the territory previously assigned to Alexandria. Of course, there still remained one minor problem in the Diocese of the East, as the clause suggests: “whilst safeguarding the privileges granted to the church of the Antiochenes.” The problem was that there yet remained two metropolitan bishops in a single civil diocese: in Antioch and in Jerusalem. Because that situation remained, the council needed to make it clear that the Metropolitan of the Diocese, the bishop of Antioch, retained the chief Metropolitan privileges. Thus, when the council announced the recent episcopal ordinations, the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Antioch was described in diocesan terms, but the jurisdiction of the bishop of Jerusalem was described in provincial terms:

“Over the most ancient and truly apostolic church at Antioch in Syria, where first the precious name of ‘Christians’ came into use, the provincial bishops and those of the diocese of the East came together and canonically ordained the most venerable and God-beloved Flavian as bishop with the consent of the whole church, as though it would give the man due honour with a single voice. … We wish to inform you that the most venerable and God-beloved Cyril is bishop of the church in Jerusalem … was canonically ordained some time ago by those of the province…” (Council of Constantinople, Synodical Letter)

This was the new status quo. Alexandria now presided over the whole Diocese of Egypt, Antioch presided over the whole Diocese of Oriens, while Jerusalem retained provincial jurisdiction within its own province. Over the course of the seventy years between Constantinople and Chalcedon, the canons of Nicæa were thus modified to reflect the change in the civil organization of the empire. At Chalcedon (451 A.D.) the Church formally and canonically accepted that change.

As we noted in Anatomy of a Deception, the Latins and the Greeks at Chalcedon disagreed on the recent editorial modification to the 6th canon of Nicæa regarding Roman primacy, but there was one editorial modification that both sides agreed on: the jurisdiction of the Metropolitan of Alexandria was no longer to be defined by the provinces of “Egypt, Libya and the Pentapolis,” but by the civil Diocese of Egypt. The Latin version now read:

“Egypt is therefore also to enjoy the right that the bishop of Alexandria has authority over everything, since this is the custom for the Roman bishop also.” (Richard Price & Michael Gaddis, The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon, vol 3, in Gillian Clark, Mark Humphries & Mary Whitby, Translated Texts for Historians, vol 45 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2005) 85)

The Greek version now read:

“Let the ancient customs in Egypt prevail, namely that the bishop of Alexandria has authority over everything, since this is customary for the bishop of Rome also.” (Price & Gaddis, vol 3, 86)

Whatever else they may have disagreed about, both parties plainly understood that there was no further value in carrying forward Nicæa’s provincial description of Alexandrian jurisdiction. The diocesan description would now suffice. That editorial modification was of no small significance, especially since the collective conviction of the assembled bishops was that the canons of Nicæa could not, and must not, be changed. Only a civil reorganization in Egypt could account for it.

Price & Gaddis, in their commentary on the acts of the council, overlooked the civil reorganization that precipitated the change in the canon, and reacted with surprise at the “omission of Libya and Pentapolis” in both versions—in the Greek and in the Latin. This, they assumed, was an error that was “perhaps to be attributed to copyists” (Price & Gaddis, vol 3, 86n). But there had been no error. The church had finally adapted to Diocletian’s reorganization into civil dioceses, and had also adapted to the late fourth century modifications that made Egypt a separate diocese from Oriens.

In any case, the formation of the Diocese of Egypt had solved the problem of defining jurisdiction of the Metropolitan of Alexandria. Regarding the jurisdiction of Jerusalem, however, it was still part of the Diocese of the East, and of course could participate in Diocesan affairs. Nevertheless, “the privileges granted to the church of the Antiochenes in the Nicene canons” were to be preserved (Council of Constantinople, Canon 2), which meant that Jerusalem’s metropolitan prerogatives remained provincially constrained.

In other words, Antioch was still the chief Metropolis of what was left of Oriens, and Jerusalem was still located within the diocese. And if two Metropolitans of necessity had to reside in a single civil diocese, their authority would still need to be defined provincially, but only one could be the Metropolitan of the Diocese. In the Diocese of Oriens, that one Metropolitan had always been the bishop of Antioch.

And, not insignificantly, in the Diocese of Italy, that one Metropolitan had always been the bishop of Milan.

The Roman Precedent

What then was the meaning of Nicæa’s clause about “a similar custom” regarding the Bishop of Rome? The answer to that question lies in the language of Nicæa. The issue at hand was that of Metropolitan jurisdiction, and the specific challenge before the council was to define the limits of Metropolitan prerogatives when two or more resided within a single civil diocese.

Remarkably, the Bishop of Rome had provided an exact counterpart to the situation in Alexandria. In the Diocese of Italy, Milan was the Metropolitan city, and yet the Bishop of Rome operated in that diocese by carving out a defined geographic boundary, within which he could exercise provincial metropolitan authority. When the council of Nicæa encountered a similar situation in Oriens, the Roman solution was the obvious choice, and the language of Nicæa reflected that: Antioch was the chief Metropolis of the Diocese of Oriens, and yet the bishop of Alexandria would operate in that diocese by carving out a defined geographic boundary within which he could exercise provincial metropolitan authority, “for a similar custom exists with reference to the bishop of Rome.”

It had worked for Rome. There was no reason it could not work for Alexandria. And for Jerusalem, as well. Nicæa’s appeal to the Roman precedent, that practice lately adopted since the creation of the dioceses, had not been an appeal to Roman Primacy at all, but instead had referred in diminutive terms to Rome’s limited, provincial metropolitan prerogatives within the Diocese of Italy. In the same way, the council would confer on Alexandria similarly limited prerogatives within Oriens. Nicæa’s language was not based on a common understanding of Roman Primacy, but on the universal understanding that the Bishop of Rome was not even the chief Metropolitan of the Diocese of Italy.

At least, not yet.

Rome’s Transition to the Metropolis of Italy

The history of Rome’s transition to Metropolis of the Diocese of Italy begins with the crisis of the third century (235 – 284 A.D.). During the crisis, internal strife had divided the Roman Empire into three competing states and left it on the verge of economic collapse. When Diocletian was proclaimed Emperor in 284 A.D., his first order of business was to decentralize power by means of the Tetrarchy. Removing the administration of the empire from Rome to the cities of the Tetrarchs, prevented anyone from challenging the empire simply by invading Rome. Instead, such a challenge would require the invasion of four separate capital cities, which was well nigh impossible. With the power removed from Rome, the Tetrarchs ruled from their four capitals of Nicomedia (modern Izmit, Turkey), Sirmium (modern Sremska Mitrovica, Serbia), Mediolanum (modern Milan, Italy) and Augusta Treverorum (modern Trier, Germany). Diocletian then established each Tetrarch over three of the twelve dioceses:

Nicomedia was over the Dioceses of Oriens (the East), Pontus and Asia.

Sirmium was over the Dioceses of Thrace, Moesia and Pannonia.

Augusta Treverorum was over the Dioceses of Britain, Gaul and Vienne.

Mediolanum (Milan) was over the Dioceses of Italy, Spain and Africa

In the process of this decentralization, Rome was reduced in power, prestige and prominence, having received neither the seat of a Tetrarch, nor the authority over one of the twelve dioceses. That made Milan, not Rome, the chief Metropolis of the Diocese of Italy. To this fact Athanasius was still plainly testifying as late as 358 A.D. in his History of the Arians. When describing the various bishops who had suffered under the persecution, Athanasius included bishop “Dionysius of Milan, which is the Metropolis of Italy” (Athanasius, History of the Arians, Part IV, chapter 33). Elsewhere, Athanasius identified the various bishops who were banished under the persecution, and he included in the list Liberius, bishop of Rome, Eusebius, bishop of Vercelli, Italy, and Dionysius, the Metropolitan of Italy:

“Even very lately, while the Churches were at peace, and the people worshipping in their congregations, Liberius, Bishop of Rome, Paulinus , Metropolitan of Gaul, Dionysius , Metropolitan of Italy, Lucifer, Metropolitan of the Sardinian islands, and Eusebius of Italy, all of them good Bishops and preachers of the truth, were seized and banished , on no pretence whatever, except that they would not unite themselves to the Arian heresy, nor subscribe to the false accusations and calumnies which they had invented against me.” (Athanasius of Alexandria, Apologia de Fuga, chapter 4)

Thus, up to the latter part of the fourth century, it was Milan, not Rome, that was still considered the chief metropolis of the Diocese of Italy. Eventually, the Metropolitan of Rome would supersede the Metropolitan of Milan and usurp from him the authority over the Diocese. But it had not always been this way.

Cyprian of Carthage provides an excellent perspective on Rome as a lesser metropolitan leading up to Diocletian’s reorganization. In Epistle 39 (251 A.D.), Cyprian was writing to his flock about a joint council with Rome on the matter of “the Lapsed” (see Treatise 3, “On the Lapsed”). In that letter to the church in Africa about that council with Rome, Cyprian referred to the Roman delegation as “the city clergy”:

“And although it was once arranged as well by us as by the confessors and the city clergy [clericis urbicis], and moreover by all the bishops appointed either in our province or beyond the sea, that no novelty should be introduced in respect of the case of the lapsed unless we all assembled into one place…” (Cyprian of Carthage, Epistle 39, paragraph 3).

That reference to “the city clergy” arises again in Letter 44, this time as Cyprian compares the vast expanse of his episcopate to the rather small domain of “the city,” Rome, in which a recent schism had occurred. There had been a division in Rome regarding the election of bishop Novatian, who in turn had sent messengers to Cyprian’s African province with letters announcing his ordination. Cyprian did not want his flock to be “disturbed by the wickedness of an unlawful ordination” in Rome (Cyprian, Letter 40), but to be sure, he had sent emissaries to obtain “a greater authority for the proof of your [Cornelius’] ordination” (Cyprian of Carthage, Letter 44, paragraph 3). But something had gone wrong in the communications. To Cornelius’ indignation some of Cyprian’s bishops were no longer addressing their letters to Cornelius as bishop, but were instead addressing their communications to the clergy of Rome. No offense was intended, Cyprian assured him. It is just that information about “a schism made in the city” does not travel as rapidly in Africa, “since our province is wide-spread”:

“For we, who furnish every person who sails hence with a plan that they may sail without any offence, know that we have exhorted them to acknowledge and hold the root and matrix of the Catholic Church. But since our province is wide-spread, and has Numidia and Mauritania attached to it; lest a schism made in the city should confuse the minds of the absent with uncertain opinions, we decided… that letters should be sent you by all who were placed anywhere in the province” (Cyprian of Carthage, Epistle 44, paragraph 3)

This diminutive reference to Rome would not have been so significant had Cyprian not already identified the Roman delegation as “the city clergy.” This time, he seems to remind Cornelius that the letters of Novatian regarding the schism in his city of Rome are infecting the bishops of Africa with “uncertain opinions,” which were doubly difficult to correct because Cyprian’s province was so “wide-spread.”

Cyprian’s situation in Africa was hardly unique. It was not as if Carthage alone was “wide-spread” and all the other Metropolitans had smaller more manageable jurisdictions. They all had large provinces to manage. But Cyprian does not seem to think Cornelius and “the city clergy” are as sympathetic as they would be if they, too, had a large province to manage. Thus, they needed to be reminded occasionally that other Metropolitans’ jurisdictions were not so small—at least, not so small as the Bishop of Rome’s. This, of course, was prior to Diocletian’s division of the empire, but even after the division, the data indicates that the the status quo remained unchanged. In the eyes of Diocletian, Rome as a city remained a lesser, but independent metropolis within the greater Diocese of Italy, and that Diocese was governed from Milan.

As we discussed in Anatomy of a Deception, Constantine was concerned about the ability of certain powerful individuals—potentiores—to impose undue influence on his otherwise independent judiciary. He composed two communications to the leaders there, one to the Vicar of Italy in Milan, and another to the Prefect of the City of Rome. In both cases, he instructed the officials on how they personally should resolve matters involving potentiores. In both cases, Constantine instructed that potentiores within their respective territories were to be handled directly by them. Note that Constantine plainly addresses the Vicar of Italy and the Prefect of Rome as if they had two distinctly different jurisdictions, even though they were both located within the bounds of the Diocese of Italy:

Constantine Augustus to Silvius, Vicar of Italy (325 A.D.): “That Your Gravity, already intent on other business, not be burdened by heaps of rescripts of this sort, We have decreed to impose on Your Gravity only those cases in which a powerful person can oppress a weak or inferior judge.” (Theodosian Code, 1.15.1; Pharr, Clyde, The Theodosian Code and Novels, and the Sirmondian Constitutions (Princeton University Press, 1952) 25)

Constantine Augustus to Maximus Valerius, Prefect of the City of Rome (328 A.D.): “If any very powerful and arrogant person should arise, and the governors of the provinces are not able to punish him or to examine the case or to pronounce sentence, they must refer his name to Us, or at least to the knowledge of Your Gravity.” (Theodosian Code, 1.16.4; Pharr, 28)

Though located within the same civil diocese, the Vicar of Italy in Milan and the Prefect of the City of Rome, had defined geographic jurisdictions assigned to them within the diocese. Noteworthy, we think, is the fact that these letters were contemporary to Nicæa.

This same rubric appears to have been in effect leading up to the Council of Sardica in 343 A.D.. For some reason, bishop Julius of Rome refers to “these parts” in the city of Rome, as if they were a distinctly different entity from greater Italy:

“[T]he sentiments I expressed were not those of myself alone, but of all the Bishops throughout Italy and in these parts.” (Athanasius, Apologia Contra Arianos, Part I, chapter 2, Letter of Julius to the Eusebians at Antioch, paragraph 26)

Another writer, by way of example, uses similar terms again to distinguish between “the city of Rome” and “the parts of Italy”, noting that “Athanasius returned from the city of Rome and the parts of Italy” (Athanasius of Alexandria, Historia Acephala, chapter 2). It was normative to consider them as two separate entities.

In view of the historical differentiation between the City and the Diocese, we can understand why in the Canons of Sardica (343 A.D.), bishop Hosius would distinguish between the general rule of appealing to the Metropolitan “in any province,” and the special case of appealing to the Bishop of Rome if the appellant happened to lodge his appeal in that city. Rome was the Italian exception in this regard, in that its bishop exercised the prerogatives of a Metropolitan within a city in a diocese that was otherwise ruled from the metropolis of Milan:

“This also, I think, follows, that, if in any province whatever, bishops send petitions to one of their brothers and fellow bishops, he that is in the largest city, that is, the metropolis, should himself send his deacon and the petitions,… But those who come to Rome ought, as I said before, to deliver to our beloved brother and fellow bishop, Julius…” (Council of Sardica, Canon 9)

This was an acknowledgment of Rome’s unique position within the Diocese of Italy, and Hosius had simply codified Rome’s Metropolitan jurisdiction within its defined geographic boundaries. Outside the city of Rome, but within the bounds of Italy, an appeal could be lodged directly with the Metropolitan in Milan. But inside Rome’s jurisdiction, the appeal would have to be lodged with the Bishop of the city, rather than with the metropolitan of the Diocese.

That this was the common understanding was evidenced only a few years hence by Athanasius would explicitly distinguish between the Bishop of Rome, who presided in Rome, and the Metropolitan of Italy, who presided from Milan, as we noted above. In fact he did so repeatedly. In his Apology Against the Arians, Athanasius identifies the victims of banishment, and separates the Bishop of Rome from the Bishops of Italy in his list:

“But when they not only endeavoured to convince by argument, but also endured banishment, and one of them is Liberius, Bishop of Rome, …, and since there is also the great Hosius, together with the Bishops of Italy, and of Gaul, and others from Spain, and from Egypt, and Libya, and all those from Pentapolis … ” (Athanasius, Apologia Contra Arianos, Part II, chapter 6, paragraph 89).

In another work, Athanasius refers to Eustorgius, Bishop of Milan as “Eustorgius of Italy” in the same sentence that he describes Julius and Liberius as Bishops of Rome:

“Had these expositions of theirs proceeded from the orthodox, from such as the great Confessor Hosius… or Julius and Liberius of Rome, … or Eustorgius of Italy, …—there would then have been nothing to suspect in their statements, for the character of men is sincere and incapable of fraud.” (Athanasius of Alexandria, Ad Episcopus Aegypti et Libyae, paragraph 8)

And again, describing Bishops by region, Athanasius lists the Bishop of Rome as distinguished from the Bishops of Italy, Spain, Gaul, and Sardinia, noting that Dionysius of Milan and Eusebius of Vercelli were the Italian bishops:

“But when I had already entered upon my journey, and had passed through the desert , a report suddenly reached me , which at first I thought to be incredible, but which afterwards proved to be true. It was rumoured everywhere that Liberius, Bishop of Rome, the great Hosius of Spain, Paulinus of Gaul, Dionysius and Eusebius of Italy, Lucifer of Sardinia, and certain other Bishops and Presbyters and Deacons, had been banished because they refused to subscribe to my condemnation.” (Athanasius of Alexandria, Apologia ad Constantium, 27)

Clearly, in the mind of Athanasius, Milan was “the metropolis of Italy,” while the city of Rome enjoyed a limited jurisdiction within that diocese. It is Milan that is identified as the Metropolis of Italy, and its Bishop as the Metropolitan of Italy. The bishop of Rome is always identified with the city, and is never the Metropolitan of Italy.

Eventually, of course, Rome would usurp Milan as the Metropolis of the diocese. This can be seen clearly in Pope Leo’s fraudulent insistence that the Canons of Nicæa require disputes to be resolved by the apostolic See of Rome, which meant to him that a synod must be convened in Italy. As we noted in Anatomy of a Deception, Pope Leo fraudulently appealed to the Canons of Sardica (343 A.D.) as if they were from Nicæa (325 A.D.), claiming that Nicæa had recognized Rome’s “right of cognizance” in all disputes. Based on that erroneous appeal to Nicæa, Leo insisted that disputes were to be “transferred to our jurisdiction” (Pope Leo I, Letter 14, paragraph 8), and resolved by “the Apostolic See” (Pope Leo I, Letter 6, paragraph 5), which required “a general synod to be held in Italy” (Pope Leo I, Letter 44, paragraph 3). To Leo in 449 A.D., the Metropolis of Rome was co-identified with the Diocese of Italy, as if Rome had been Metropolis of the Diocese all along. But such language would have been unthinkable a hundred years earlier, when the City of Rome and the Diocese of Italy were two distinctly separate administrative entities, separately administered.

In fact, the transition had begun much sooner than Leo. At the Council of Carthage in 418 A.D., the African bishops awaited further information to determine if what was “directed to us from the Apostolic See” is really that which is “kept according to that order by you in Italy” (Canon 134, The Code of Canons of the African Church). The Roman delegate attending this council was not a member of “the city clergy,” as he had been in Cyprian’s day, but now was bishop “Faustinus of the Potentine Church, of the Italian province Picenum,” on the northern coast of Italy (An Ancient Introduction, The Code of Canons of the African Church). Italy, it appeared, was now being managed from Rome. Pope Damasus I had done his work well way back in 382 A.D., when he proclaimed at the Council of Rome that “the holy Roman church is given first place by the rest of the churches” (Council of Rome, III.1). But Rome had not always been given first place.

To the contrary, as late as 358 A.D., Milan enjoyed the distinction as the chief metropolis of Italy, and as late as 358 A.D., Rome was still considered to be a smaller geographic unit within the larger diocese, just as she had been since the first days of Diocletian’s reorganization, and just as she had been during the Council of Nicæa. That was the “similar custom” invoked in Canon 6, the practice lately adopted by Rome since Diocletian’s reorganization of the Empire.

Because of her limited authority within a broader diocese that was governed from Milan, Rome had presented to the bishops of Nicæa the exact solution they needed to solve the problem of Alexandrian jurisdiction within a broader diocese that was governed from Antioch. Although Antioch was the chief seat of the Diocese of Oriens, Alexandria would be treated as a Metropolitan See within it, exercising its ancient authority within the provincial confines of Egypt, Libya and the Pentapolis, “since a similar custom exists with reference to the bishop of Rome.”

As we noted above, when they analyze the historical data outside of the context of civil and ecclesiastical history, Rome’s apologists say that Canon 6 of Nicæa suddenly has teeth. But we know better. When Canon 6 is analyzed in its civil and ecclesiastical context, all the teeth of Roman Primacy are removed, and modern Rome is left making its fraudulent claims of primacy on the authority of her dentures alone.

Next week we will show how Rome’s misconception of Canon 6 of Nicæa has been perpetuated since the latter part of the 4th century. Misunderstanding the civil and ecclesiastical context of the canon has led to the application of a gross anachronism in order to maintain Rome’s fraudulent claims to primacy.

Follow

Follow

Tim wrote:

“That dispute was the matter of Metropolitan jurisdiction and the boundaries within which a Metropolitan bishop was authorized to act. The myth that resulted from Nicæa’s solution was the false belief that the Council had acknowledged the primacy of the Bishop of Rome.”

and:

“The importance of this jurisdictional issue is plainly evident not only from the context of Canon 6, but from the canons of the subsequent councils. The Council of Sardica (343 A.D.) restated the policy, namely that the bishop of one diocese may not “ordain to any order the minister of another from another diocese without the consent of his own bishop” (Council of Sardica, Canon 15).

The Council of Constantinople (381 A.D.) restated the policy that “Diocesan bishops are not to intrude in churches beyond their own boundaries nor are they to confuse the churches: but in accordance with the canons, the bishop of Alexandria is to administer affairs in Egypt only.” (Council of Constantinople, Canon 2)

The Council of Ephesus (431 A.D.) restated the policy again, insisting that the bishop of one diocese was not to take possession of another man’s territory: “The same principle will be observed for other dioceses and provinces everywhere. None of the reverent bishops is to take possession of another province which has not been under his authority from the first or under that of his predecessors” (Council of Ephesus).

The matter of Metropolitan jurisdiction arose again at the Council of Chalcedon (451 A.D.). Canonically prohibited from aspiring to another man’s Metropolitan seat, some bishops were appealing to the civil authorities to create a new civil province, and with it, a new Metropolitan seat. But this practice was creating the problem of two separate civil provinces—and therefore two Metropolitan seats—within a single ecclesiastical province:

“It has come to our notice that, contrary to the ecclesiastical regulations, some have made approaches to the civil authorities and have divided one province into two by official mandate, with the result that there are two metropolitans in the same province.” (Council of Chalcedon, Canon 12)

Thus, from the Meletian schism in 307 A.D. to the Council of Chalcedon in 451 A.D., the matter of Metropolitan jurisdiction was at the forefront of conciliar polity, and Nicæa was always considered to be the authoritative standard.”

Wow, this now is crystal clear. The idea that a Roman Bishop has central authority over the catholic, universal Church not only violates Scripture (who declares the Romish system Anti-christ) but it violates historical, faithful church court rulings forbidding such a central Romish head of multiple jurisdictions.

This is so clear, why does not every Roman Catholic denounce the Pope in Rome of violating both Scripture and faithful court decisions?

These national churches being formed sound a lot like Presbyterianism and nothing like Roman Catholicism. Finally, starting to see the true biblical Presbyterian church model with precedence in early Church history. Excellent.

It started in the early church, and then it reached its pinnacle height in Scotland:

“That Presbyterial Church Government and manner of worship are alone of divine right and unalterable; and that the most perfect model of these as yet attained, is exhibited in the Form of Government and Directory for Worship, adopted by the Church of Scotland in the Second Reformation.”

“It started in the early church, and then it reached its pinnacle height in Scotland:”

WALT! Enough already with the Scottish nonsense!

Tim wrote:

“Over the course of the fourth century, however, a partial solution presented itself, and when it did, the jurisdiction of Alexandria suddenly began to be described in diocesan rather than provincial terms. Sometime between the councils of Nicæa in 325 A.D. and Constantinople in 381 A.D., the Diocese of Oriens was split into two civil dioceses—the Diocese of the East, which encompassed Syria and Palestine, and the Diocese of Egypt, which encompassed the provinces previously assigned to Alexandria. It is at the council of Constantinople that we first begin to see the Diocese of Oriens distinguished from the Diocese of Egypt, both in the canons and in the Synodical Letter.”

Interesting….here starts the slippery slope toward antichrist.

“9. Constantine was in Britain in 306, when he was appointed Caesar at his father’s death. Acclaimed as Augustus in 307 and in 308, Constantine administered the West until 324, when he became sole sovereign.” (page 112, Roman State and Christian Church)

The fact that the Roman empire wanted everything under a sovereign control is timely with Constantine.

“The purest Churches under heaven are subject both to mixture and error: (k) and some have so degenerated, as to become no Churches of Christ, but synagogues of Satan.(l) Nevertheless, there shall be always a Church on earth, to worship God according to His will.(m) (k) I Cor. 13:12; Rev. 2 and 3; Matt. 13:24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 47. (l) Rev. 18:2; Rom. 11:18, 19, 20, 21, 22. (m) Matt. 16:18; Ps. 72:17; Ps. 102:28; Matt. 28:19, 20.” –The Westminster Confession of Faith, Chapter 25:5

“How the Scots Invented the Modern World: The True Story of How Western Europe’s Poorest Nation Created Our World and Everything in It”

“Mention of Scotland and the Scots usually conjures up images of kilts, bagpipes, Scotch whisky, and golf. But as historian and author Arthur Herman demonstrates, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries Scotland earned the respect of the rest of the world for its crucial contributions to science, philosophy, literature, education, medicine, commerce, and politics—contributions that have formed and nurtured the modern West ever since.

Arthur Herman has charted a fascinating journey across the centuries of Scottish history. He lucidly summarizes the ideas, discoveries, and achievements that made this small country facing on the North Atlantic an inspiration and driving force in world history. Here is the untold story of how John Knox and the Church of Scotland laid the foundation for our modern idea of democracy; how the Scottish Enlightenment helped to inspire both the American Revolution and the U.S. Constitution; and how thousands of Scottish immigrants left their homes to create the American frontier, the Australian outback, and the British Empire in India and Hong Kong.”How the Scots Invented the Modern World reveals how Scottish genius for creating the basic ideas and institutions of modern life stamped the lives of a series of remarkable historical figures, from James Watt and Adam Smith to Andrew Carnegie and Arthur Conan Doyle, and how Scottish heroes continue to inspire our contemporary culture, from William “Braveheart” Wallace to James Bond.

Victorian historian John Anthony Froude once proclaimed, “No people so few in number have scored so deep a mark in the world’s history as the Scots have done.” And no one who has taken this incredible historical trek, from the Highland glens and the factories and slums of Glasgow to the California Gold Rush and the search for the source of the Nile, will ever view Scotland and the Scots—or the modern West—in the same way again. For this is a story not just about Scotland: it is an exciting account of the origins of the modern world and its consequences.

“The point of this book is that being Scottish turns out to be more than just a matter of nationality or place of origin or clan or even culture. It is also a state of mind, a way of viewing the world and our place in it. . . . This is the story of how the Scots created the basic idea of modernity. It will show how that idea transformed their own culture and society in the eighteenth century, and how they carried it with them wherever they went. Obviously, the Scots did not do everything by themselves: other nations—Germans, French, English, Italians, Russians, and many others—have their place in the making of the modern world. But it is the Scots more than anyone else who have created the lens through which we see the final product. When we gaze out on a contemporary world shaped by technology, capitalism, and modern democracy, and struggle to find our place as individuals in it, we are in effect viewing the world as the Scots did. . . . The story of Scotland in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is one of hard-earned triumph and heart-rending tragedy, spilled blood and ruined lives, as well as of great achievement.”

—FROM THE PREFACE

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/how-the-scots-invented-the-modern-world-arthur-herman/1103378055?ean=9780307420954#productInfoTabs

“How the Scots Invented the Modern World: The True Story of How Western Europe’s Poorest Nation Created Our World and Everything in It”

“Mention of Scotland and the Scots usually conjures up images of kilts, bagpipes, Scotch whisky, and golf.”

It used to. But that was before you ruined it for me. Whenever I think of anything Scottish an image of a buffoon wearing a kilt sitting at his keyboard banging out anti-Catholic bile on this blog interjects itself into my imagination.

Jim wrote:

“It used to. But that was before you ruined it for me. Whenever I think of anything Scottish an image of a buffoon wearing a kilt sitting at his keyboard banging out anti-Catholic bile on this blog interjects itself into my imagination.”

Rutherford wrote:

“The Lord stirred up our nobles to attempt a reformation in the last age, through many difficulties, and against much opposition from those in supreme authority; he made bare his holy arm, and carried on the work gloriously, like himself, his right hand getting him the victory, until the idolatry of Rome, and her cursed mass, were dashed; a hopeful reformation was in some measure settled, and a sound Confession of Faith was agreed upon, by the Lords of the Congregation.”

Any independent mind and brain can see the incredible difference between truth and fiction in both statements.

Jim represents histories devilish mass that has enslaved more souls, minds and hearts toward the guarantee of hell than any other self-proclaimed religion in history.

Rutherford represents the true, biblical reformed Christian church in history that not only exposed Rome for what she was and now globally has become, but showed in history in the Scottish reformation how they removed Rome from their soil and prospered into the greatest country in the world bringing more inventions and blessing to the world than any other nation.

Rome has caused in history more death, blood and destruction to the world. Scotland has brought more blessing as a reformed and covenanted nation to Christ.

No POPE in Scotland, only the Lord Jesus Christ as the sole Prophet, Priest and King of His Christian Church.

You forgot about POPE WALT!

What about pope CK? How do you decide which regional synods you accept and which you reject? Which ecumenical councils you accept and which you reject? Which papal statements you accept and which you reject? Doesn’t it all come down to CK’s personal opinion?

Thanks,

Tim

“Beyond all question, the written word doth teach what is a right constituted court, and what not, Psal. 10. What is a right constituted house, and what not, Josh. 24:15. What is a true church, and what is a false one; what is a true church, and what is a synagogue of Satan, Rev. 2. What is a clean camp, and what is an unclean. We are not for an army of saints, and free of all mixture of ill affected men; but it seems a high prevarication, for churchmen to counsel and teach, that the weight and trust of the affairs of Christ, and his kingdom, should be laid upon the whole party of such as have been enemies to our cause, contrary to the word of God, and the declarations, remonstrances, solemn warnings, and serious exhortations of his church, whose public protestations the Lord did admirably bless, to the encouragement of the godly, and the terror of all the opposers of the work.

I mean not any visible reign of Christ on earth, as the Millenaries fancy; I believe (Lord, help my unbelief,) the doctrine of the holy prophets, and the apostles of our Lord Jesus Christ, contained in the books of the Old and New Testament. to be the undoubted truth of God, and a perfect rule of faith, and the only way of salvation. And I do acknowledge the sum of the Christian religion, exhibited in the Confessions and Catechisms of the reformed Protestant churches, and in the National Covenant, divers times sworn by the king’s majesty, the state, and Church of Scotland, and sealed by the testimony and subscription of the nobles, barons, gentlemen, citizens, ministers, and professors of all ranks. As also, in the Solemn League and Covenant of the three kingdoms of Scotland, England, and Ireland. And I do judge, and in conscience believe, that no power on earth can absolve, and liberate the people of God from the bonds and sacred ties of the oath of God.

The Church of Scotland had once as much of the presence of Christ, as to the power and purity of doctrine, worship, discipline, and government, as any we read of, since the Lord took his ancient people to be his covenanted church. The Lord stirred up our nobles to attempt a reformation in the last age, through many difficulties, and against much opposition from those in supreme authority; he made bare his holy arm, and carried on the work gloriously, like himself, his right hand getting him the victory, until the idolatry of Rome, and her cursed mass, were dashed; a hopeful reformation was in some measure settled, and a sound Confession of Faith was agreed upon, by the Lords of the Congregation. The people of God, according to the laudable custom of other ancient churches, the Protestants in France and Holland, and the renowned princes in Germany, did carry on the work in an innocent, self-defensive war, which the Lord did abundantly bless. When our land and church were thus contending for that begun reformation, those in authority did still oppose the work; and there was not then wanting men from among ourselves, men of prelatical spirits, who, with some other time-serving courtiers, did not a little undermine the building; and we, doating too much upon sound parliaments, and lawful general assemblies, fell from our first love, to self-seeking, secret banding, and little fearing the oath of God.”

AMEN.

http://www.covenanter.org/Rutherfurd/rutherfurdtestimony.htm

Subscribed at first by the King’s Majesty, and his Household, in the year 1580; thereafter by persons of all ranks in the year 1581, by ordinance of the Lords of secret council, and acts of the General Assembly; subscribed again by all sorts of persons in the year 1590, by a new ordinance of council, at the desire of the General Assembly: with a general bond for the maintaining of the true Christian religion, and the King’s person; and, together with a resolution and promise, for the causes after expressed, to maintain the true religion, and the King’s Majesty, according to the foresaid Confession and acts of Parliament, subscribed by Barons, Nobles, Gentlemen, Burgesses, Ministers, and Commons, in the year 1638: approven by the General Assembly 1638 and 1639; and subscribed again by persons of all ranks and qualities in the year 1639, by an ordinance of council, upon the supplication of the General Assembly, and act of the General Assembly, ratified by an act of Parliament 1640: and subscribed by King Charles II. at Spey, June 23, 1650, and Scoon, January 1. 1651.

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/National_Covenant_of_the_Church_of_Scotland

Tim,

You said Lucifer was the metropolitan of the Sardican islands.

Now you have really went and done it! Everybody with a brain knows Lucifer is metropolitan of hell!

Tim,

Correct me if I am wrong, it seems you are defining what the church is teaching from within those inside the church, however, there is a significant amount of influence from Constantine that is detailed in Roman State and Christian Church legal source documents. Have you considered to refute those legal documents written by Constantine which make claims to the Roman Church as I see some called him a “super-Pope” due to his promotion of the “Catholic Church”.

“Though the epistle is quite hortatory in its endeavour to compose this religious controversy, which rapidly was eviscerating eastern Christendom and would divide presently the Roman world for two generations and would require two general counsels (2) before its settlement, yet the letter can be considered as of some legal importance. …

But Constantine could not be kept long indifferent to this important question, for, after he had found that this epistolary effort was futile, he convoked the First Ecumenical Council of the Christian Church to assemble at Nicaea in 325, when and where he saw to it that “the faith once delivered unto the saints” (3) was defined.” (pg.114).

In your next article supporting your position, can you look closer at the legal authority of the civil government in the affairs of the council?

You said:

“As we noted above, when they analyze the historical data outside of the context of civil and ecclesiastical history, Rome’s apologists say that Canon 6 of Nicæa suddenly has teeth. But we know better. When Canon 6 is analyzed in its civil and ecclesiastical context, all the teeth of Roman Primacy are removed, and modern Rome is left making its fraudulent claims of primacy on the authority of her dentures alone.”

I see one reference on page 128:

“Here today has been given to you power over all the Church, over the priesthood and over the Empire, and over all the order(10) which are subjected to the priesthood and to the Empire. It is to you from whom the Lord will demand accounting for all the Church’s lost and recovered children.”

Perhaps this “super-pope” Constantine is the true line to the Roman Catholic religion, and indeed is the basis for which all other Pope’s claim their authority. Peter is not the true line at all for the Papal system, but Constantine is their true line?

Here is another one:

“God has given to you power over the priesthood and has given to me power over the Empire. But today God gives you power over the priesthood and over the Empire. I am subject to you and I shall follow your orders.” (pg. 128)

“Perhaps such a threat as this, when coupled with the emperor’s words as reported at the Council of Nicaea in 325 (see 49, I), explains “why Constantine called the first great council …. why he placed himself as super-pope to formulate the faith of the Christian world and then to resume his sceptre of super-kaiser in order to see that all his subjects obeyed, not only the policeman, but the priest as well …. The great Constantine had spoken …. The orthodox alone were deemed fit to become saints and all who favored another creed were officially branded as criminals condemned to suffer, not merely the wrath of God on earth, but eternal damnation in a world of which neither party could speak with historical precision.” (pg. 141).

What is beginning to look like to me as that the Roman Catholic church got its authority to rule the world from Constantine, and this has nothing to do with Peter whatsoever.

Could it be possible that this is where the Fraud started for Rome? You wrote:

“Misunderstanding the civil and ecclesiastical context of the canon has led to the application of a gross anachronism in order to maintain Rome’s fraudulent claims to primacy.”

Perhaps Rome does not want to claim they received universal power over the Christian Church from Constantine, but from the legal documents I’m reading it sure seems like they got this authority from him. Some of these bishops and church leaders seem to give him UNIVERSAL authority over all the Christian world and over all the Priests…indeed like a Super-pope.

What am I missing? I see no link to Peter for Rome’s claims, but I see lots of links to Constantine as their master pope!

Thanks, Walt,

There is no link to Peter for Rome’s claims of primacy, of course. As Firmilian of Cæsarea said, “they who are at Rome … vainly pretend the authority of the apostles” (Cyprian of Carthage, Letter 74, From Firmilian, Against the Letter of Stephen, paragraphs 3 & 6). Further, as Cyprian also said, Peter never would have claimed the primacy: “For neither did Peter, whom first the Lord chose, and upon whom He built His Church, … arrogantly assume anything; so as to say that he held the primacy…” (Cyprian of Carthage, Epistle 70, paragraph 3). As Mathetes wrote in the second century, “For it is not by ruling over his neighbours, or by seeking to hold the supremacy over those that are weaker, or by being rich, and showing violence towards those that are inferior, that happiness is found; nor can any one by these things become an imitator of God” (The Epistle of Mathetes to Diognetus, chapter 10). The idea of a strong, central, Roman, Papal, Petrine episcopate on earth was foreign to the early church. At least until the latter part of the 4th century.

Regarding your other observations, I would not see Constantine’s words to the council as evidence of Roman Catholic primacy for the simple reason that the council of Nicæa was not a Roman Catholic council, as much as Rome would like it to have been. It is not Constantine who made Roman Catholicism the official religion of the empire—Roman Catholicism did not even exist yet. It was Emperor Theodosius with his De Fide Catholica in 380 A.D. who made Roman Catholicism the official religion of the empire.

My point in this article, and the one to follow is simply to show that the historical context of Canon 6 completely changes the meaning of the Roman precedent that was used to arrive at the Alexandrian solution at Nicæa. The language of various church men from Cyprian through Athanasius shows that Rome was a smaller, independent entity within what Diocletian created as the greater Diocese of Italy, and was not its chief Metropolis. And if that was the case, the bishops at the Council of Nicæa could not have been appealing to Roman Primacy for Canon 6. It would not have even entered their minds. Their use of Rome as an example served a much different purpose than to invoke “primacy.”

What is also apparent is that in order to achieve primacy, Rome ultimately had to usurp the authority of three “kings” of the divided Roman empire. I only touched on this in A See of One, but left off simply at Rome’s claims to the three Dioceses of Italy, Oriens and Egypt. What I did not cover at that time was how Rome had usurped three kings to do it. By my reckoning, thirteen “horns” arose from the Roman Empire, and those thirteen dioceses each had a chief metropolitan. In order to take over, Rome had to usurp the metropolitan of Milan, the metropolitan of Antioch and the metropolitan of Alexandria in order to end up with those three Dioceses and the three “Petrine Sees,” thus fulfilling the prophecy of Daniel 7:8,20,24.

As I noted in A See of One, there had to be ten “horns” left standing after the little horn removed three, which means first of all that there must have been thirteen horns to start with, and second that there must have been a little fourteenth horn, the little horn of Daniel 7, that “came up among them.” Rome, the city-diocese, was actually that “little horn,” the fourteenth diocese that arose in the midst of the rest, “before whom there were three of the first horns plucked up by the roots.” “He shall subdue three kings,” refers to the Metropolitans of Milan, Alexandria and Antioch. Rome could not have arrived at its final position of primacy without somehow dealing with the authority of those three Metropolitans.

For now, the primary purpose of the article is to show that the civil and ecclesiastical history of the dioceses of Egypt, Oriens and Italy do not lend themselves to the Roman Catholic interpretation of the 6th Canon of Nicæa.

Thanks,

Tim

Tim,

“It is not Constantine who made Roman Catholicism the official religion of the empire—Roman Catholicism did not even exist…”/

Who ever said it was?

Just today I was talking with a friend about the 40 Martyrs of Sebaste. They were martyred 7 years of after the Edit of Milan and just a few years before the Council of Nicea.

There is no way people who would choose death over compromising with paganism would abandon the faith en masse as your crackpot theory stolen from Trail of Blood and Hislop suggest.

Only Walt and Balloni would buy it.

Jim, you wrote,

I agree. I do not believe the ante-Nicene and Nicene church abandoned the faith.

I do not believe I have ever suggested that the Nicene church fell into apostasy.

Thanks.

Tim

Tim,

Your theory is just a variant view of the standard cant. You pepper yours with more historical minutiae that nobody has time to look up ( and you don’t supply sources for ), that’s all,

I asked you days ago to explain how you would refute a Mormon. In principal, you are almost identical give or take 350 years.

Before that I asked you about Strauss, Baur, Renan, etc. the guys who naturalized Jesus just as you do the Church he founded.

Your practice is to stick and move onto another article, never getting bogged down in a clinch by explaining things ( like Penal Substitution for instance ).

Tim wrote:

“It is not Constantine who made Roman Catholicism the official religion of the empire—Roman Catholicism did not even exist yet. It was Emperor Theodosius with his De Fide Catholica in 380 A.D. who made Roman Catholicism the official religion of the empire.”

I guess I was thinking that Constantine in his claim, and the claim made about him by others, that he was sovereign over the world and over the priesthood that he was by definition a “super-pope” as some claimed. If indeed he had authority over both the civil Roman world, as well as the priesthood, then I can see support for all the letters I’ve been reading in Roman State and Christian Church.

Certainly this would not fit your post millennial eschatology, and it does not fit ours either where we see the great transition in 800 AD with Charlemagne, but I’m thinking more of the “theory” that the Roman Papacy adopted that they are the sole head of the Christian Church.

If Constantine claimed was recognized as the sole head of the Christian Church and Roman State, and this “idea” was developing with him and his “super-pope” status, I could see future generations in the Christian Church look to others inside Rome to replace him as a “head” over the worldwide Church, and later (Stephen II) and Charlemagne as head of both Church and State.

Yes, I see now where Roman Catholicism was established:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_Fide_Catolica

I see it was an Edict. I found it on page 335 in Roman State and Christian Church (vol. 1) entitled “Edict of Gratian, Valentinian II, and Theodosius I on Establishment of the Catholic Religion, 380”

Yes, I just read the intro and footnotes to the edict. Very interesting what they say about Peter and how the Roman Catholic religion took over the term for universal Catholic.

Tim, see this (page 364):

“(2) it no longer sets the faith of the bishops of Rome and of Alexandria as the standard of conformity (no. 167), but substitutes the Nicene Creed of eastern origin, probably because the Emperor, now in the East, observed that the re-establishment of orthodoxy there could be consummated only by the action from the East’s own orthodox ranks, whose resentment against Italian and Egyptian interference was intermittent.”

Does not the Roman Catholic apologists like Jim claim that Rome and the Roman Pope was in charge of the entire visible Christian church in 381?

Hmmm, I guess Rome does not talk about this “Mandate … on Adherence to the Nicene Creed” in 381 a year after their religion was formed vs. adherence to the Pope.

I was so happy to see the Mandate above as it conforms to our reformed faith which identifies 3 universal formularies as the basis for the universal church…nothing to do with any Popes.

The Universal Formularies

– The Apostle’s Creed (200?-500?)

– The Nicene Creed (381)

– The Athanasian Creed (415?-550?)

Check out these guys. Everything they say about Mormonism can be applied to them.

Tim,

I am so slow! It just clicked.

I was studying the map of the various provinces or “dioceses” the Roman Empire was divided up into you provide at the top of the article and it struck me as weird that you opted to use the foreign word, “diocese” rather than “province” or “region” or some other word more in use by native English speakers, especially Bible Christians who mistrust anything North of the Mason Dixon Line.

Who has dioceses? The ROMAN Catholic Church! It all makes sense now. The pieces of the puzzles all fit together so nicely.

Tim, your logic is irrefutable. Downright brilliant. Your hints and inferences are so convincing to sheep like Walt.

Jim,

“Diocese” is not a foreign word for “province.” It is the English word for “diocesis.” The diocesis is a geographical unit invented by Emperor Diocletian. It is named after him. The first use of the term “Diocese” was by Diocletian when he divided the empire into dioceses.

Thanks,

Tim

I thought I could let Jim do all the talking but I just had to do this cause TIM’s FUNNY!

He said:

“Diocese” is not a foreign word for “province.” It is the English word for “diocesis.” The diocesis is a geographical unit invented by Emperor Diocletian. It is named after him. The first use of the term “Diocese” was by Diocletian when he divided the empire into dioceses.”

DIOCESE

From διοικέω (dioikéō) + -σις (-sis).

/di.o͜ɪ́.kɛː.sis/ → /ði.ˈy.ki.sis/ → /ði.ˈi.ci.sis/

Noun

διοίκησις • (dioíkēsis) (genitive διοικήσεως); f, third declension

1.housekeeping, control, government, administration

2.one of the lesser Roman provinces 1.(as an Ecclesiastical division) a bishop’s jurisdiction, diocese

The word wasn’t named after Diocletian. It’s Greek for administration. Another example of Tim’s “alternative” history.

Thanks, Bob,

I stand corrected. The diocesis was not named for Diocletian. Thanks for providing the etymology.

Tim

Jim said – You pepper yours with more historical minutiae that nobody has time to look up ( and you don’t supply sources for ), that’s all,

Me – if it weren’t for BOB most people would of bought your history of the word diocese . I don’t buy most of you write because you tend to do exactly what Jim said. Throw in your faulty analysis and incredible imagination and you get, well… Your usual posts.

Fair enough. I’ve made mistakes and I own them. I have no problem with that. But what about pope CK? How do you decide which regional synods you accept and which you reject? Which ecumenical councils you accept and which you reject? Which papal statements you accept and which you reject? Doesn’t it all come down to CK’s personal opinion?

As I’ve more than once explained, I am willing to stipulate the fact that I am a fool, saying things that nobody will believe, writing articles that nobody will read. It may well be that I wear pajamas and live in my mother’s basement. Let’s just assume that I am a fool.

That said, What about pope CK?

Thanks,

Tim

Tim,

Do Presbyterians have dioceses? Are states divided up into counties or dioceses? ( Yes, Louisiana is divided into parishes but not dioceses. Are school districts called dioceses?

“Diocese’ is right up there with “ex opere operato”, “supererogation” and the scariest phrase of them all, “hocus pocus”.

Kudos to Bob for taking the time to dig up the definition. I personally don’t bother rolling up my sleeves and doing any serious research as I smell what your game is from the start.

Hints. innuendos and planting little seeds of doubt.

Jim,

Perhaps you could help move the conversation along by pointing out where I have ever alleged that the name “diocese” is the critical link to antichrist. I just don’t understand the origin of your question, and I don’t recall making that point.

If I understand correctly, you said I was using the word “diocese” instead of “province” in order to establish some link between Roman Catholicism’s use of “diocese” and Diocletian’s use of “diocese.” Then you argued against my alleged attempt to do so, which is a textbook case of a straw man argument. But I don’t recall ever attempting to make such a link.

Diocletian divided the empire into 12 dioceses in 293 A.D.. By the end of the 4th century, there were 13 dioceses, which are the necessary 13 “horns” of Daniel 7 for there to be ten remaining after three are removed, as implied by Daniel 7:7, Revelation 13:1, 17:3,12,16. Papal Rome was the “fourteenth dioceses” that came up among the rest and removed three. In the process of establishing a “see of one,” to use Gregory the Great’s term, and in order to claim the “three Petrine Sees” of Rome, Alexandria and Antioch, and with them the dioceses of Italy, Egypt and Oriens, Rome had to usurp the authority of bishop of Milan, the Metropolitan of Italy, the bishop of Alexandria, the Metropolitan of Egypt, and the bishop of Antioch, the Metropolitan of Oriens. Antichrist Rome thus fulfilled Daniel 7:8, “…before whom there were three of the first horns plucked up by the roots” and Daniel 7:24, “and he shall subdue three kings.”

All of this would remain the same even if Diocletian called the geographical units “dioceses” and Roman Catholicism changed their names to something else. The fact is, however, that Roman Catholicism “received” the empire, complete with its names and hierarchical organization, and it is not I, but Roman Catholic apologist Taylor Marshall who sees the fulfillment of Daniel 7:26 in Roman Catholicism’s takeover of the operations of the empire. Daniel 7:26 reads, “And the kingdom and the dominion and the greatness of the kingdoms under the whole heaven shall be given to the people of the most high,” which Marshall sees fulfilled in the fact that “The Roman Empire became a tool in the hand of the Church.” The empire was under new management.

The English word diocese is just the word that historians use in English to describe the diocesan division of the empire under Diocletian. “Diocese” is not the critical link here, and my use of the term is not intended to do anything other than convey the facts of history using the terms of history. Roman Catholicism’s fulfillment of prophecy is the critical link, and Roman Catholicism would fulfill the prophecy even Diocletian called the territories dioceses and Roman Catholicism called the same territories “ecclesiarchies” or some other such name.

The name, Diocese, is not the critical link at all. If I have ever alleged that it is, please let me know where I have done so, in order that I might correct it.

Thanks for any clarifications you can offer,

Tim

Tim,

I just read a piece by Bryan Cross how the god Orpheus appears in the catacomb of St. Calixtus.

Add that to “Diocese” and you should really give the zenophobic and bigoted yokels the willies.

This is for Tim;

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-QnBWL_d-5A

This is for Walt;

Walt,

Some weeks ago you revealed that you had never even heard of the central doctrine of your Calvinist religion.

Tim dummied up and never explained ot to you despite your plea for him to tell you.

Maybe this satirical video by Lutherans will help you understand the unbiblical/antibiblical teaching you unwittingly subscribe to.

This is great! I can refute Tim’s theory that the Church fell away into Romishism in the latter half of the 4th century without ever appealing to a single specifically Catholic doctrine.

Same goes for his false views of the atonement and the sacraments.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JwxHzo0QVYY

Walt,

How do you think James White does against this Arminian guy?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zbEnNiIlujw ( It is the Arminian guy’s very first debate ).

Tim,

Please notice Mr. Flowers says Clement was chosen by Peter and followed him as Bishop of Rome ( around 1 hour and 10ish minutes.

Also, Flowers brings out none of your pre-350 A.D. Fathers taught Calvinism. Explain that, please.

Guys, this video is NOT Romish propaganda.

Tim,

Once again I am having difficulty navigating your comment section so I will just jump to the end of the comments column to post.

You are trying to stick CK with the old “Tu Quoque” smoke and mirrors that a guy named Robert tried using for about two years over on CCC. All he succeeded in doing was making his position even more unworkable ( books NEVER talk, people sometimes do ).

Read this. http://www.calledtocommunion.com/2010/05/the-tu-quoque/

Jim,

You observed,

Hardly. Actually, I am just trying to figure out what method CK uses to decide what to believe. It is not an attempt to prove or deny the superiority of either system. In fact I believe Roman Catholicism and Sola Scriptura are epistemologically equivalent in that they both start with a single axiom, one unprovable assumption.

My question to CK has nothing to do with whether sola scriptura is superior or inferior to Roman Catholicism.

In any case, my question dates back to January when CK said the whole problem with Protestantism is that each Protestant is the final say. To this, I responded that I do not understand CK’s epistemology:

That would be a legitimate question, even if Protestantism ceased to exist today. After all the dust settled, and everyone was either Roman Catholic or pagan, the question would remain:

CK has never answered that question, and no Roman Catholic can really explain it.

Jim, you have on occasions corrected other Roman Catholics who don’t believe Vatican II was even necessary, much less an infallible source of doctrine. Yet as you know, William Most relied heavily on Vatican II in order to determine that Mary’s virginity being preserved in partu was an infallible teaching of the church.

So there are two Roman Catholics, one of whom thinks Vatican II was a waste of time, and another who thinks that it is indispensable on the matter of an infallible teaching of the church. Both think they understand the mind of the church. Which position am I to accept? On what basis? How do I know which is true and which is just personal opinion?

Let’s assume for the sake of argument that there had never been a schism in 1054 and never a reformation, and the whole world was constantly at peace under the guidance of Roman Catholicism. How is it possible that one thinks Vatican II was a waste of time and the other thinks it is indispensable. How does a Roman Catholic weigh the Synod of Carthage in 258 and the synod of Rome in 382 and determine that the former was not infallible, but the latter one was, even though neither were ecumenical and therefore neither fall under the promised protection of infallibility?

That’s a question Roman Catholics could justifiably ask each other even if there had never been anything on earth but Roman Catholicism.

Do you know the answer to the question? More importantly, does CK?

Thanks,

Tim

“Roman Catholicism and Sola Scriptura are epistemologically equivalent in that they both start with a single axiom, one unprovable assumption.”

Which is…?

Any Catholic who says Vatican II was a waste of time needs to explain what he means.

Jim,

The axiom of Sola Scriptura is that the Bible alone is the word of God. The axiom of Sola Ecclesia is that The Roman Catholic church is the church that Jesus Christ founded upon Peter and his successors.

Start with the first Axiom and you end up identifying Roman Catholicism as the antichrist. Start with the second Axiom, and you end up with Roman as the true church, which conclusion is in fact is no different than the Axiom itself, which is circularity. That is why Roman Catholics can never arrive at the realization that their church is the antichrist, because it is a conclusion that is inconsistent with their axiom.

You also observed,

Why should he have to? On whose authority? Jim’s?