The city of Rome was the capital seat of the empire at its founding, and retained that primacy for centuries. But for a brief period from 293 A.D. to the latter part of the fourth century, Rome was relegated to the status of a third tier Metropolis behind the tetrarch capitals and the metropolitan seats of Diocletian’s new dioceses. The division of the empire started in 293 A.D. with the formation of 12 dioceses under four tetrarchs, presiding from Nicomedia, Smirmium, Milan and Trier. Each tetrarch was assigned the rule over three dioceses, and each diocese was in turn ruled from its chief metropolis by a vicarius or equivalent. Notably, the city of Rome was reduced in stature, and was made neither a tetrarch capital, nor even the chief metropolis of the Diocese of Italy. Nevertheless, the city of Rome was also assigned its own vicarius, and he ruled over his limited jurisdiction in the heart of Italy. Over the course of the fourth century, the tetrarchy faded away, but the diocesan system endured. Further reorganizations occurred in which two dioceses were combined into one, and two others were divided into four. The eventual outcome by the end of the fourth century was a fully reorganized Roman empire of thirteen dioceses under thirteen vicars—and within one of those dioceses, a greatly diminished city of Rome, a comparatively small vicariate in an empire of dioceses. Although the Vicar of Rome had not received a diocese to manage, the city of Rome and its suburbs comprised what could almost be called a little diocese of their own. We might even call it “the fourteenth diocese.” That little “fourteenth diocese” had been diminished in Diocletian’s reorganization, but under the administration of a pope, it would one day rise up again to rule the empire. Only three metropolitan cities stood in his way, and he would dispatch them short order.

It was in that little “fourteenth diocese” that Christ is alleged to have established the chief metropolis of His kingdom on earth, a matter of no small significance to Roman Catholic apologists. Taylor Marshall, for example, wrote his book The Eternal City to explain “why … Christ our Lord [would] choose the pagan city of Rome” as the capital city of His new kingdom (Taylor Marshall, The Eternal City, p. 6). The matter was quite simple to Marshall—Christianity had inherited the Roman Empire, just as it had been prophesied to do:

“As we see in Daniel 2, ‘[Rome’s] sovereignty shall be left to another people’ and it would happen through the introduction of a stone or rock – a Petros or Peter!” (Taylor Marshall, The Roman Church as Prophesied in the Old Testament)

Thus, says Marshall, the Roman Catholic church “receives the Roman empire” from its previous custodians, and we agree with him on that specific point. Roman Catholicism received the empire from Rome, taking over on its ascent that which the empire was abdicating on its decline. We even agree with Marshall that this is precisely what Daniel had foreseen. What the bishop of Rome had received in the process was a diminished city that no longer even served as the capital of a declining empire. By then, Rome and its suburbs comprised a little “diocese” that as late as 358 A.D. had still been considered the lesser of two metropolitan seats in the Diocese of Italy. But as Daniel well knew, little dioceses can grow up to do very big things, and that is precisely what the “little fourteenth diocese” did. That “little fourteenth diocese” was nothing other than the Little Horn of Daniel chapter 7.

We understand that when we set out to write an article on Daniel chapter 7 and to identify the chief antagonist of the vision, tradition dictates that we ought to have identified a ten-way division of the Roman Empire, and then an eleventh character that upsets the status quo. If we are to identify the empire’s fragmentation into dioceses as the fulfillment of Daniel 7, tradition insists that there should have been ten dioceses, plus a chief antagonist—an eleventh diocese—that rises up to uproot three of them and rule the remaining seven. After all, Daniel had seen in his vision that the Fourth Beast “had ten horns.” As Daniel considered the situation, the antagonist arose from the midst of the fragments, and that antagonist had plucked up three of the other horns, and in doing so, captured the attention of a prophet:

“I considered the horns, and, behold, there came up among them another little horn, before whom there were three of the first horns plucked up by the roots: and, behold, in this horn were eyes like the eyes of man, and a mouth speaking great things.” (Daniel 7:8)

The traditional interpretation is well nigh universal: the Roman empire is prophesied to be fragmented ten ways, and three of those ten fragments would be displaced by antichrist. Most Christians today hold to that tradition, and many still await that ten-way division, cautiously but confidently anticipating the rise of a future antichrist to rule the world, removing three “horns” in the process, and then reigning over the remaining seven.

But we do not hold to that tradition, and the reason for this is quite simple: there are fourteen, not eleven, horns in Daniel’s vision.

At this point we invite our readers to return to Daniel chapter 7, and read it closely, noticing three things:

1) Each of the first four empires is described in its final, not its initial, configuration;

2) Daniel never says that “the first horns” were ten in number; and

3) Daniel never says that “three of the ten” horns were removed.

Based on the text, therefore, we suggest to our readers that the expectation of a ten-way division of the fourth empire is but a tradition, and prophecy does not bow to tradition. The Roman Empire was to be divided 13 ways, and that is precisely what Daniel had foreseen.

On the first point listed above, we invite our readers to visit our article, A See of One, in which we analyzed this in more detail. Briefly, the Lion is figured as being “lifted up from the earth, and made stand upon the feet as a man, and a man’s heart was given to it” (Daniel 7:4). That description portrays a time after Nebuchadnezzar’s humiliation (Daniel 4:33-37), which is what we could call the final configuration of the Babylonian empire, before Darius the Mede took over (Daniel 5:31). The Bear is depicted already raised up on one side and is commanded to “devour much flesh” (Daniel 7:5). That description depicts the period of Persian dominance, for in the Medo-Persian empire, the Persians “came up last” (Daniel 8:3). The Leopard is already depicted with four heads (Daniel 7:6), and there is no mention of the first king who by that time had already been removed from the scene (Daniel 8:8). That description portrays the final four-way division of the Greek empire after the death of Alexander (Daniel 8:22, 11:4). And significantly, the fourth beast of Daniel 7 has ten horns, which we take to refer to its final configuration, after three of “the first horns” had already been uprooted to make room for the Little Horn, the fourteenth, to come up. Notably, when Daniel sees that fourteenth horn coming up, he is coming up among the ten that remained.

This is consistent with what we see in Revelation 17:12, in which the chief antagonist has with him not seven but ten horns rallying to his cause, and they “receive power as kings one hour with the beast.” If the Little Horn had removed three of the ten before coming up, there should have been only seven remaining to receive power with him, and only seven to “hate the whore” (Revelation 17:16). The “ten horns” can hardly “give their power and strength unto the beast” (Revelation 17:13) if three of the ten have already been cut off at the roots. Thus, there must remain ten horns, even after the rise of Antichrist. Ten. Always ten (Daniel 7:8, Revelation 12:3, Revelation 13:1, Revelation 17:3, 7, 12, 16). And if there were ten left after he removed three, then there must have been thirteen to begin with. Otherwise either the representations in Revelation have three too many horns, or the historical interpretation of Daniel 7 ends with three too few.

On the second point listed above, we simply note that at no place in the narrative does Daniel say that “the first horns” were only ten in number. He simply says that the Fourth Beast “had ten horns” (Daniel 7:7). He does not describe the horns as they came up (as he did with the four in Daniel 8:8, 22), and he does not say that “at first it had ten horns” or “it had ten horns, which were the first.” He merely says that it “had ten horns,” just as the Third Beast “had … four heads” (Daniel 7:6). No one would suggest either that the Greek Empire had started with four heads, or that Daniel had somehow overlooked Alexander. Nor would anyone suggest that the First Empire had begun after Nebuchadnezzar’s humiliation, or that the Second Empire started with the Persians in charge. Daniel acknowledges the unfolding of history—i.e., “I beheld till…” (Daniel 7:4)—but then proceeds to describe each beast in its final configuration. Just as Daniel’s description of the Third Empire does not in any way suggest that there had never been a first king before the four-way division, his vision of the Fourth Empire does not in any way suggest that there had only been ten horns to begin with. He had described Greece in its final configuration after the first head was gone, and he described the Fourth Beast in its final configuration, after three horns had been removed.

This leads us to the third point on our list. Although it is often assumed, Daniel never actually says that “three of the ten” horns were removed. Here are Daniel’s references to the three horns, and we note that the “first horns” are never enumerated as “ten” and the three horns are never described as “three of the ten”:

“before whom there were three of the first horns plucked up by the roots:” (Daniel 7:8)

“And of the ten horns that were in his head, and of the other which came up, and before whom three fell;” (Daniel 7:20)

“And the ten horns out of this kingdom are ten kings that shall arise: and another shall rise after them; and he shall be diverse from the first, and he shall subdue three kings.” (Daniel 7:24)

In Daniel 7:8, he does not say “three of the ten were plucked up.” In 7:20 he does not say “before whom three of the ten fell,” and in 7:24 he does not say “he shall subdue three of the ten kings.” In other words, what may be called the most universally accepted tradition regarding Daniel 7 assumes something that Daniel never actually says, namely that “three of the ten” horns were uprooted to make room for the Little Horn. As we have noted above, there must have been thirteen to begin with, and three of the thirteen must have been removed in order to prepare the way for the fourteenth horn to come up among the remaining ten, and to become “more stout than his fellows” (Daniel 7:20).

And that is exactly what happened.

So how did the Bishop of Rome’s little fourteenth diocese finally “subdue three kings” (Daniel 7:24) and eventually take over the Roman Empire? And how did three fall before him (Daniel 7:20) so that he could rule the known world? And how were three of the thirteen “plucked up by the roots” (Daniel 7:8)?

The answer lies, as it often does with Roman Catholicism, in the latter part of the fourth century, and the three Metropolitan seats that stood in the Little Horn’s way were Milan, Alexandria and Antioch, the three capitals of the Dioceses of Italy, Egypt and Oriens.

Taking Out Milan

To begin, we invite the attention of our readers to the map of the Diocese of Italy at the head of the article. Notice first that under Diocletian’s reorganization, Milan, not Rome, was the chief Metropolis of Italy. William G. Sinnigen explains that at first, even though Italy was a single diocese, it was exceptional in the sense that there were two vicars there—one in Milan and one in Rome:

“The reforms of Diocletian and Constantine included Italy in the diocesan and prefectural organizations. Technically the whole region south of the Alps formed one diocese within the praetorian prefecture of Italy. It was partitioned between two vicars [in Milan and in Rome], however, each of whom administered an area which, from a practical point of view, was a separate diocese.” (Sinnigen, William G., “The Vicarius Urbis Romae and the Urban Prefecture,” Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte Bd. 8, H. 1 (Jan., 1959), p. 98)

Thus, in Milan, the chief metropolis of the diocese, there was the Vicar of Italy. But within the diocese, there was another Vicar, the Vicar of Rome. Edward Gibbon explains for us the historical oddity of that second Vicar in the diocese—a vicar no doubt, but of some limited jurisdiction, and without a formal diocese of his own. After describing the thirteen dioceses, Gibbon added:

“In Italy there was likewise the Vicar of Rome. It has been much disputed, whether his jurisdiction measured one hundred miles from the city, or whether it stretched over the ten southern provinces of Italy.” (Gibbon, Edward, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, vol 2, (London: Methuen & Co., ©1901) , 170, n118)

The actual limited jurisdiction of the Vicar of Rome within the Diocese of Italy “has been much disputed” indeed, but what has not been disputed is the fact that the diocesan Vicar was the one who resided in Milan. In the ecclesiastical domain, too, the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Rome had for many years been recognized to be limited in scope.

Long before Diocletian’s reorganization, we see that the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Rome did not encompass all of Italy. As we described in our article, False Teeth, thirty years before Diocletian’s reign, Cyprian described the Roman delegation at an ecumenical council as “the city clergy” (Cyprian of Carthage, Epistle 39, paragraph 3). We also highlighted his observation that a recent controversy in Rome was “a schism made in the city,” and in comparison to Rome’s jurisdiction, Cyprian’s “province is wide-spread” (Cyprian of Carthage, Epistle 44, paragraph 3). Thus in the third century, Rome’s dominion was understood to be comparatively small, limited to “the city.”

After Diocletian’s reorganization, Rome’s jurisdiction remained limited, and Rome’s bishop continued to oversee a territory much smaller than the Diocese of Italy. As we also noted in our follow-up article, “Unless I am Deceived…”, early in the fourth century the Council of Nicæa had used the bishop of Rome as an example of how two metropolitan bishops could operate peaceably within a single civil diocese. Because Alexandria and Antioch were both located in the same civil Diocese of Oriens, the council had to define Alexandria’s jurisdiction within Oriens in provincial terms instead of diocesan terms. In the process, the council revealed the common understanding of Rome’s limited jurisdiction within the Diocese of Italy. Alexandria’s metropolitan jurisdiction within the Diocese of Oriens was limited in nature and was provincially constrained to Egypt, Libya and Pentapolis. The Bishop of Rome had set a relevant precedent for the council, for Rome’s metropolitan jurisdiction within the Diocese of Italy was provincially constrained, as well. The council therefore recognized the propriety of limiting Alexandria’s provincial metropolitan jurisdiction within the Diocese of Oriens, “since a similar custom exists with reference to the bishop of Rome” in the Diocese of Italy (Council of Nicæa, Canon 6 (325 A.D.)). This, too, spoke of Rome’s limited jurisdiction.

By 358 A.D., Athanasius was still describing Milan as the chief Metropolis of the Diocese of Italy (Athanasius, History of the Arians, Part IV, chapter 33), and was still speaking of the Bishop of Milan as the chief Metropolitan of the Diocese (Athanasius of Alexandria, Apologia de Fuga, chapter 4). Thus we see from the historical records—both civil and ecclesiastical—that Rome did not start out as the chief Metropolitan of the Diocese. And yet today, the Bishop of Rome is addressed as the Primate of Italy. When did Rome supplant Milan as the chief Metropolis?

As we noted in our article, False Teeth, sometime between 358 A.D. and 418 A.D., it became clear that Rome’s dominion had expanded to include all of Italy, and Milan’s prerogatives as Metropolitan of Italy had been usurped. This was true in both the secular and the ecclesiastical domains. In the secular realm, historians note that the office of vicarius Italiae was eliminated and its jurisdiction transferred from Milan to Rome around 402 A.D.:

“The lack of detailed information regarding the vicar of Rome during the fifth century is all the more unfortunate since it was during this period that the second echelon of administration as a whole was undergoing important changes. By the beginning of the fifth century all vicars had moved up two steps in the hierarchy … [but] The vicarius Italiae was permanently eliminated, probably in 402 [A.D.]” (Sinnigen, 108-9)

That this same change occurred in the Roman Catholic church is evidence by the change in conciliar language over the same period. As we noted in False Teeth, under the section entitled, “Rome’s Transition to the Metropolis of Italy,” the boundaries of Roman jurisdiction had expanded well beyond “the city,” and now included the whole Italian peninsula. The Roman delegation was no longer called “the city clergy” as in Cyprian’s day, but now included bishops from well beyond the city itself. Likewise, Rome was by then presumed to speak for the whole of Italy itself (Council of Carthage, Canon 134, The Code of Canons of the African Church). Early in the fifth century, Rome’s patriarchal sway was clearly Italian, and no longer merely Roman.

The actual transition of ecclesiastical primacy in Italy from Milan to Rome may reasonably be traced to the Council of Rome in 378 A.D.. It was at that council that a letter of petition was sent to Emperors Gratian and Valentinian II, requesting that they recognize and enforce a policy that all Metropolitans, including that of Milan, were subordinate to Rome. The letter specifically names the civil Vicar of Italy in Milan as an officer who may arrest uncooperative metropolitan bishops and bring them to Rome for trial:

“Therefore … to avoid our seeming to make ourselves a nuisance to you by raising numerous legal cases in future, we ask your Clemency, that your Piety deign to order that any bishop who has been condemned either by the sentence of [Pope] Damasus, or by that of us bishops who are Catholics, and yet wishes to retain his church illegally, or who when summoned by a court of bishops obstinately refuses to appear, is to be summoned and brought to the city of Rome either by the illustrious praetorian prefects of your Italy, or by its vicar; … if the man is himself a metropolitan, he is to make his defense without delay nowhere other than at Rome, or before such judges as the bishop of Rome shall appoint for him… Our above-mentioned brother Damasus, seeing that he has received the distinction of your verdict (of acquittal) in his case, ought not be placed in a position inferior to those who are his equals in office, but whom he excels in the prerogative of the apostolic see, (which is what he would be) if he was seen to be subject to jurisdiction of the public courts, from which your law has exempted priests. In making this request he does not appear to be refusing to accept the judgment after the verdict has been pronounced, but rather to be claiming privilege, which you have awarded.” (Liebeschuetz, John H. W. G., Ambrose of Milan: Political Letters and Speeches (Liverpool University Press, 2001) 252-253, Petition of the Council of Rome to Emperors Gratian and Valentinian II 9, 10).

We observe the contrast here between the Council of Rome in 378 A.D. and that of Sardica in 343 A.D.. As we noted in our series, Anatomy of a Deception, the council of Sardica addressed the problem of the church becoming a nuisance to the Emperor’s court by limiting the prerogative of appeal to the Emperor through the Metropolitan “in any province whatever” (Council of Sardica, Canon 9). The intent at Sardica had been to eliminate the nuisance by reducing the volume of appeals to the emperor.

But the intent at the Council of Rome was to eliminate the nuisance by cutting off the Imperial appeals process entirely, and redirecting disputes to the Bishop of Rome. In the process, it became clear that Milan was no longer the chief Metropolis of Italy. Rome now enjoyed that prerogative. Thus, four years later at another Council of Rome (382 A.D.), Pope Damasus declared that “the holy Roman church is given first place by the rest of the churches without [the need for] a synodical decision” (Council of Rome, III.1). This, only forty years after bishop Julius had dutifully forwarded his judicial decision to the Imperial Court in Milan for review (Athanasius, Apologia Contra Arianos, Part I, chapter 2, paragraph 20), after which the Council of Sardica was convened by the emperor to review Julius’ decision (Athanasius, Apologia Contra Arianos, Part I, chapter 3).

Thus, by the end of the fourth century it was clear that the ecclesiastical Diocese of Italy was now effectively being administered from Rome, and the prerogatives of the Bishop of Milan, who had only recently been called the Metropolitan of Italy (Athanasius of Alexandria, Apologia de Fuga, chapter 4), were being exercised by the bishop of the southern metropolis. As with the civil domain, so with the ecclesiastical. Milan had been reduced in stature from its position as the chief metropolis of one of the thirteen dioceses of the empire, effectively making the Bishop of Rome the Primate of Italy.

Taking Out Alexandria and Antioch

With the Diocese of Italy safely under his belt, only Alexandria and Antioch stood in the way of the Roman Bishop’s ambition. The problem with Alexandria was that in the eyes of the Emperor, the city stood eye-to-eye with Rome in stature. When the emperor declared Roman Catholicism to be the official religion of the Empire (De Fide Catholica), he had identified it as the religion both of the pontiff in Rome and of the bishop of Alexandria. That was a status Rome could not long share with another.

The problem with Antioch was that there yet existed the perception that Peter had first begun to build the church there, and therefore that Antioch actually retained some element of “Petrine primacy”—at least in a chronological sense. Peter, after all was presumed to have presided there as bishop long before the church had been established at Rome. For this reason the metropolis yet enjoyed some privileges on that account, for the Lord, it was believed, had bid Peter to “tarry here for a long period (Chrysostom, Homily on St. Ignatius, 4). That, too, was a status Rome could not long share with another.

Both Alexandria and Antioch therefore presented problems to Roman primacy, and those problems would have to be addressed. The usurpation of the prerogatives of Alexandria and Antioch therefore followed immediately upon Rome’s usurpation of Milan. At that same council of Rome in 382 A.D., Pope Damasus first expressed the theory of “the Three Petrine Sees,” identifying Rome, Alexandria and Antioch as the three chief sees of the Roman Catholic religion, in that order. This, he said, was because these three sees were all Petrine in origin, but Rome, he insisted, was chief. In his declaration, he carefully placed Alexandria between Rome and Antioch, relegating Antioch to third place to ensure that its chronological primacy could in no way threaten Rome’s claims of ecclesiastical primacy:

“Therefore first is the seat at the Roman church of the apostle Peter ‘having no spot or wrinkle or any other [defect]’. [Ephesians 5:27] However the second place was given in the name of blessed Peter to Mark his disciple and gospel-writer at Alexandria, and who himself wrote down the word of truth directed by Peter the apostle in Egypt and gloriously consummated [his life] in martyrdom. Indeed the third place is held at Antioch of the most blessed and honourable apostle Peter, who lived there before he came to Roma and where first the name of the new race of the Christians was heard.” (Council of Rome, III.1)

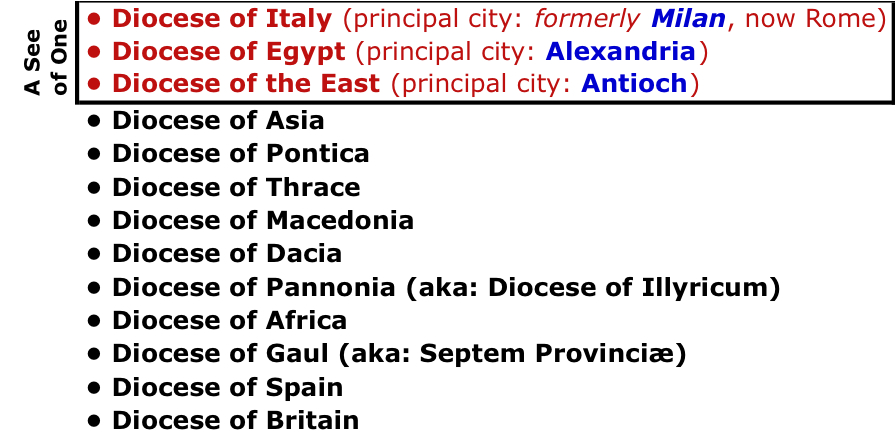

As we highlighted in our article, A See of One, Rome had thereby claimed as its own, under a newly refined dogma of metropolitan Petrine privilege, the chief metropoli of three of Rome’s thirteen dioceses: the Diocese of Italy, the Diocese of Egypt and the Diocese of Oriens. Based on Damasus’ claims, Pope Gregory the Great later described those three Petrine Sees as a single entity, claiming that “the See of the Prince of the apostles,” constituted as it was of the three sees of Rome, Alexandria and Antioch, “alone has grown strong in authority, which in three places is the See of one“:

“Wherefore though there are many apostles, yet with regard to the principality itself the See of the Prince of the apostles alone has grown strong in authority, which in three places is the See of one. For he himself exalted the See [Rome] in which he deigned even to rest and end the present life. He himself adorned the See [Alexandria] to which he sent his disciple [Mark] as evangelist. He himself established the See [Antioch] in which, though he was to leave it, he sat for seven years. Since then it is the See of one, and one See, over which by Divine authority three bishops now preside, whatever good I hear of you, this I impute to myself.” (Gregory the Great, Book VII, Epistle XL, To Eulogius, Bishop of Alexandria)

The Final Configuration

Thus was Milan dispatched, lest its Italian primacy stand in the way of Rome. And thus was Alexandria dispatched, lest its primacy in the new religion stand in the way of Rome. And thus was Antioch dispatched, lest its chronological primacy stand in the way of Rome. So Milan was subordinated to Rome in the Diocese of Italy, and Alexandria and Antioch were subordinated to Rome in the Dioceses of Egypt and Oriens. Three “kings” were subdued, and three “horns” were uprooted. The Little “fourteenth diocese” had “grown strong in authority … in three places,” and thereby essentially declared itself to be for practical purposes a single, powerful, authoritative ecclesiastical diocese which was “more stout than” the remaining ten (Daniel 7:20).

The final configuration of the Roman empire, therefore, may be seen in its list of Dioceses at the end of the fourth century. We show the Petrine Dioceses in red and the usurped Metropolitans in blue, and the three combined sees as one, in accordance with the claims of Popes Damasus I and Gregory the Great:

We note at this point that the Council of Rome in 378 A.D. had claimed its prerogatives based on a “privilege” which emperors Gratian and Valentinian II, “have awarded.” Two years later Theodosius I declared that Pope Damasus I was the new Pontifex of the state religion (De Fide Catholica). Two years after that, Emperor Gratian formally renounced the title Pontifex Maximus. By this means was the transfer of the rule of the Empire from pagan Rome to pagan Roman Catholicism initiated, for Roman Catholicism was simply the Fifth Empire in a series of pagan Empires Daniel had foreseen in chapters 2 and 7. By the end of the fourth century, Roman Catholicism’s novelties were on full display, as was its apostasy, and in the eyes of God, the Bishop of Rome and his “See of One” was just another pagan empire to succeed the previous one, just as Rome had succeeded Greece, and Greece had succeeded Persia.

As we observed above, we actually agree with Roman Catholic apologist Taylor Marshall on this point: Roman Catholicism received the Roman Empire from its previous custodians. At the time of the transfer, the Roman Empire was constituted of thirteen dioceses with thirteen diocesan metropoli, along with a little “fourteenth diocese” in the city of Rome. It was an administrative structure that the Roman Catholic church was only too happy to adopt. That little “diocese” occupied by the Bishop of Rome then uprooted three of the “horns” (the Dioceses of Italy, Egypt and Oriens), subdued three “kings” (the Metropolitans of Milan, Alexandria and Antioch), came up among the remaining ten to rule the empire, and became “more stout than his fellows” (the See of One). Thus was the prophecy of the Little Horn of Daniel 7 fulfilled.

We hasten to point out that that Little Horn, that “See of One,” eventually set up the Eucharist as an image to be worshiped, and that image is based on an unleavened bread ritual that imparts a mark on the hand and forehead (Exodus 13:9), and Christians were murdered during the Inquisitions for not worshiping it, and that image has long been attended by Eucharistic miracles in which it bleeds, pulsates and speaks, as we discussed in our article, If This Bread Could Talk. And as we showed in another article, that “See of One” is attended by a false prophet under the appearance of Mary, the apparitions of which insist that the people of the world increase their adoration of “her son” in the Eucharist, and which apparition has been known to reaffirm the false doctrines of Rome and make the sun appear to come down from the heavens to attest to its divine origins.

Thus, in addition to fulfilling Daniel 7, the Papacy, with the Apparitions of Mary and the Eucharistic idol, has also fulfilled Revelation 13 which warns of just such an image that comes to life and has the ability to speak, and is set up by a False Prophet that can work miracles, even to bring the fire of heaven down to earth in the sight of men:

“And he doeth great wonders, so that he maketh fire come down from heaven on the earth in the sight of men, And deceiveth them that dwell on the earth by the means of those miracles which he had power to do in the sight of the beast; saying to them that dwell on the earth, that they should make an image to the beast, which had the wound by a sword, and did live. And he had power to give life unto the image of the beast, that the image of the beast should both speak, and cause that as many as would not worship the image of the beast should be killed.” (Revelation 13:13-15)

We mention here again, as we have elsewhere, that the Roman numerals of “Vicar of the Son of God” in Latin—Vicarius Filii Dei—add up to 666, of which number John warned in Revelation 13:18.

Roman Catholicism is therefore the very antichrist of which we were informed in advance by many warnings and admonitions from the prophets and apostles. The religion is to be avoided at all costs, and the elect who are currently thinking to remain in Rome—for her liturgy, her cathedrals, her size or her feigned antiquity—are commanded to come out of her.

“Come out of her, My people…” (Revelation 18:4)

Follow

Follow

Tim said:

“The actual limited jurisdiction of the Vicar of Rome within the Diocese of Italy “has been much disputed” indeed, but what has not been disputed is the fact that the diocesan Vicar was the one who resided in Milan. In the ecclesiastical domain, too, the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Rome had for many years been recognized to be limited in scope.”

I really wish you would start to find some source documents to prove your points rather than rely on all these historians that agree with you on some points, but you disagree with them on other points. This is what drives me crazy about Bob and Jim as Roman Apologists is that they rely solely on Catholic Encyclopedias and Wikipedia to prove their Catholic tradition.

I support your need to use those authors who agree with you, especially Catholics that actually support your thesis, but none of these witnesses would be allowed in a court of law if they could not be cross examined. Primary source documents are allowed in court, but all these opinions of others are not.

Where is the source document to support “but what has not been disputed is the fact that the diocesan Vicar was the one who resided in Milan.” Do you have some source document from the Roman Civil authority that establishes this fact, or from an Ecclesiastical authority factually making this clear?

I don’t care what Gibbon says on this fact (with no references) nor what the Catholic encyclopedia says as this is a key point.

Thanks Walt. I agree with, and understand, your insistence on primary sources. I did not mean to imply that Rome’s diminished stature from 293 A.D. to the end of the 4th century should be accepted based on my personal opinion. When I said that “What is not disputed…” I was referring to the initial twelve-way division under Diocletian, and most importantly, the purpose for the division. During the Crisis of the third century (from about 234 – 284 A.D.), the empire was going through one emperor about every two years, because everyone kept invading Rome. Diocletian’s solution was to decentralize, remove power from Rome and create four new capitals, making it impossible for someone to take over the empire simply by invading one city. When Diocletian set up the tetrarchy, the four tetrarch capitals were as listed above, and Rome was not one of them. Rome’s reduced status was the natural result, and Rome was not made the Metropolitan of Italy. His actual territory is very difficult to discern based on the historical data, but the fact that it was not Italy really is not disputed (to my knowledge).

Much of this may be understood from the primary sources that I cited over the last couple weeks, including Constantine’s communications with the Vicar of Italy and the Vicar of Rome and the way Julian, Athanasius and his biographer referred to Rome and Italy as two separate entities.

In any case, reducing Rome’s stature was actually Constantine’s purpose in decentralizing the rule of the empire, and there were only four tetrarchs in his reorganization, none of which were located in Rome. Thus, Rome’s diminished stature was not just a side effect of the reorganization, but was actually its intended purpose.

As you noted in a later comment, Athansius acknowledged this in his works when he identified Milan as the metropolis of Italy, and its bishop as the Metropolitan of Italy. The church was identifying jurisdictions based on civil jurisdictions, which is why Athanasius’ letter is informative on this point—as was his recognition that by 358 A.D., the Diocese of Egypt had not been formed yet.

Anyway, I hope that answers your question. The empire was reorganized into thirteen diocese, plus a minor territory governed by the city of Rome, the fourteenth diocese, or the Little Horn of Daniel 7.

Thanks,

Tim

TIM–

The bible says the beast has this quality:

Rev 13:3 I saw that one of the heads of the beast seemed wounded beyond recovery—but the fatal wound was healed! The whole world marveled at this miracle and gave allegiance to the beast.

You say the beast is the Papacy/Romish Church? To what, then is Rev 13:3 referring?

A very good question, indeed.

Tim

And it merits a very good answer indeed. Unhappily, it is not to be found on this blog.

By the way Tim, doesn’t 666 add up to Falloni? Or Hitler, Kauffman and Kardashian?

It’s like the old city on 7 hills business that can apply to Lisbon, Portugal and several other cities.

For those readers of Tim’s interpretation of Daniel and Revelation, there is something you should know.

“The Western Roman Empire collapsed in the late 5th century. Romulus Augustulus is often considered to be the last emperor of the west after his forced abdication in 476, although Julius Nepos maintained a claim to the title until his death in 480. Meanwhile, in the east, emperors continued to rule from Constantinople (“New Rome”); these are referred to in modern scholarship as “Byzantine emperor” but they used no such title and called themselves “Roman Emperor” (βασιλεύς Ῥωμαίων). Constantine XI was the last Byzantine Roman emperor in Constantinople, dying in the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453.

Due to the cultural rupture of the Turkish conquest, most western historians treat Constantine XI as the last meaningful claimant to the title Roman Emperor, although from this date Ottoman rulers were titled “Caesar of Rome” (Turkish: Kayser-i Rum) until the Ottoman Empire ended in 1922. A Byzantine group of claimant Roman Emperors existed in the Empire of Trebizond until its conquest by the Ottomans in 1461. In western Europe the title of Roman Emperor was revived by Germanic rulers, the “Holy Roman Emperors”, in 800, and was used until 1806.”

Tim’s historist view of the Fourth Beast in Daniel does not match what actually happened in history. History is clear that the Roman Empire did not end with the fall of Rome.

Hi Tim, i had a question about the fourth beast.

Since the Bible says that after the Rise of the little Horn, in 380+/-

and that AFTER it the Roman Empire, the fourth Beast, wont exist anymore.

I want to ask:

When did the fourth beast disappear from the world stage?

I mean, when did the Roman Empire finish? Like the Fourth Beast finished his Time?

I reallife? because its a little bit difficult because the western roman empire lived different long as the east roman empire.

Bob, above, tried to disprove you. Can you adress this?

thank you!☺️

Alessandro, can you help me understand this statement: “Since the Bible says that after the Rise of the little Horn, in 380+/-

and that AFTER it the Roman Empire, the fourth Beast, wont exist anymore.”

Where do you believe the Bible says that?

oh, ehm.

i tried now to write down, but im very confused.

So the Roman Empire is judged. (first judgement in Dan 2 or 7)

Then, because of this judgement the roman empire gets into pieces (toes/horns)

And from there the little horn rises.

And takes the Power of the last Empires.

(babylon/medopersia/greek)

But what happens with the forth Beast?

From the text i understand that it disappears after being judged. Before the 3 Empires lifes are being prolonged. (7:12)

that would mean that the roman empire should have gone, before the Pope came to power in 380?

Sorry for my confusion….

Jim, Bob, CK, please take heed to this point:

“Roman Catholicism is therefore the very antichrist of which we were informed in advance by many warnings and admonitions from the prophets and apostles. The religion is to be avoided at all costs, and the elect who are currently thinking to remain in Rome—for her liturgy, her cathedrals, her size or her feigned antiquity—are commanded to come out of her.”

Don’t waste your time…do it now!

WALT

You said:

Jim, Bob, CK, please take heed to this point:

“Roman Catholicism is therefore the very antichrist of which we were informed in advance by many warnings and admonitions from the prophets and apostles. The religion is to be avoided at all costs, and the elect who are currently thinking to remain in Rome—for her liturgy, her cathedrals, her size or her feigned antiquity—are commanded to come out of her.”

Don’t waste your time…do it now!”

Yes, yes! Do what Tim and Walt say, come out of her my people and join the First United Methodist congregation in your city today! We have open communion and we can also trace our apostlicity through our Anglican roots. The Presbyterians have no line of apostolic succession so they have no authority but their own.

“Taste and see.”

Bob said:

“Yes, yes! Do what Tim and Walt say, come out of her my people and join the First United Methodist congregation in your city today! We have open communion and we can also trace our apostlicity through our Anglican roots.”

I just about fell off my chair laughing at this comment. You guys are the product of the heretic John Wesley. Learn your history before you place your self even close to the Apostle’s doctrine. Wesley is among the greatest well known heretics in the history of the world outside of Jack Van Impe, Pelagius and Arminius.

WALT–

You said: “Wesley is among the greatest well known heretics in the history of the world outside of Jack Van Impe, Pelagius and Arminius.”

Really? Who branded him a heretic and what was his heresy? Please show me the historical references, or are you just making this up?

Ok, I see you rely ***mostly*** on Athanasius as the sole source document that Milan was the Metropolitan of Italy, but no other formal mandate or edict appointing Milan such a title or authority to be taken over by Rome.

“Thus, by the end of the fourth century it was clear that the ecclesiastical Diocese of Italy was now effectively being administered from Rome, and the prerogatives of the Bishop of Milan, who had only recently been called the Metropolitan of Italy (Athanasius of Alexandria, Apologia de Fuga, chapter 4), were being exercised by the bishop of the southern metropolis. As with the civil domain, so with the ecclesiastical. Milan had been reduced in stature from its position as the chief metropolis of one of the thirteen dioceses of the empire, effectively making the Bishop of Rome the Primate of Italy.”

I think I got the two key elements to your eschatology.

1) It is critical to have an early date for Revelations pre-70AD

2) It is critical to have Milan’s central ecclesiastical authority taken over by Rome to fulfill prophetical interpretation.

Both are plausible issues. I’m not convinced yet, but as always not closed minded to such possibilities. Both points have warrant in history, but I’m not entirely sure you can use Scripture to interpret Scripture to prove them just yet. Your excellent way you have carefully defined Scripture and texts to compare them over and over has great credibility in my mind, even if it goes against my own presupposition to the text.

I’m starting to see the argument being made…and as a former Roman Catholic, and former evangelical, futurists, preterist and current historical post millennialist, I fear not changing my views based upon evidence and facts.

Think of as the opposite of the Romish robots of Jim, Bob and CK who will do anything to defend Rome at all costs…as tradition to them is sacred and absolute key to all religion. I know the feeling, growing up Catholic I was taught the same thing, but once I “came out of her my people” I put Scripture above tradition, and all things came together nicely.

Thanks, Walt. You observed, (regarding my eschatology):

That may be an accurate way to summarize it, but I should probably provide some additional information to clarify it:

It is critical to have an understanding of the Iron Period, and this may be discerned from several Scriptural sources: i) Daniel’s description of the transition from Iron to Iron and Clay in Daniel 2; ii) the fact that the Stone strikes the statue in the feet, not in the legs; iii) Jesus’ appropriate of Daniel 2 imagery in Matthew 21:44 and Luke 20:18 when He is explaining to the Jews “The kingdom of God shall be taken from you…”, remembering that the Stone strikes the statue in the feet; and iv) the significance of the timing of seven kings—five had fallen, one is, and one will last only a short while (Revelation 17:10).

When it is shown from the Scriptures that the Iron period of the Fourth Empire is comprised of 7 kings, and that the Stone strikes the statue in judgment only after the Iron period is over, and that the Kingdom is taken away from the Jews during the period of the Iron and Clay Feet, and the fact that Revelation never makes reference to the destruction of Jerusalem as a past event, it makes sense for John to be warned that we are about to arrive at the critical juncture in the statue imagery—the transition from legs to feet. That is when it all begins to unfold, eschatologically. Thus, these things “must shortly come to pass” (Revelation 1:1).

The mistake of the Preterists is to force Jesus’ judgment against the Succession of Empires to begin before the period of the Feet. That’s why they have antichrist and the seals beginning prior to the end of the Iron period. The mistake of Historicists, in my opinion, is to guard against the Preterist position by defending a late date of authorship. An early date of authorship can actually be derived from the text, and then used to show definitively that Nero was not antichcrist, for antichrist was to arise after, not during, the Iron period.

You also observed, (regarding my eschatology):

b) More accurately, it is critical to understand the structure of Diocletian’s reorganization in 293 as well as further reorganizations that took place in the fourth century. From that information, we may see what Canon 6 of Nicæa meant when it said, “for such is the custom with reference to the bishop of Rome,” which indicates that the Church understood Rome’s provincial, not diocesan, metropolitan jurisdiction, for Rome was to Milan as Alexandria to Antioch. Rome and Antioch were both metropolitans, but not chief metropolitans in the diocese where they resided. Alexandria eventually was given its own diocese (The Diocese of Egypt), but Rome was not. It had to be taken. It is true that Daniel 7 is understood when the division of the empire is in clear view, and that helps us understand Milan’s relation to Rome, but it is more than just the fact that Milan was the chief metropolis of Italy. It is also important to know that Antioch was the chief metropolis of Oriens, and Alexandria was in Oriens, but was not the chief; and further that Milan was the chief Metropolis of Italy, and Rome was in Italy, but was not the chief. That is what Rome and Alexandria had in common, and that is why the Council would say “for such is the custom with reference to the bishop of Rome” in reference to Alexandria’s relation to Antioch. Without that knowledge—and I dare say some Reformers did not have it—it looks like Nicæa recognized Rome as the chief metropolis of Italy, and therefore superior to Milan even as early as Nicea. Witness Calvin:

But Nicæa had not said anything in favor of the primacy of the Roman See or assigning it first place. That is something Calvin read into it, not understanding the significance of Diocletian’s reorganization. My point here is simply that it’s not just about Milan—it’s about the whole reorganization. Put it into its proper scriptural context and you have a little “fourteenth diocese,” as it were, rising among 13, usurping three kings and uprooting three dioceses and becoming more stout than his fellow, as prophesied.

So, to summarize, it is critical to have an understanding of the transition from Legs to Feet in Daniel 2, and it is important to have an understanding of the Diocletian and 4th century reorganization of the empire that Daniel was prophesying.

Thanks,

Tim

Tim,

Thank you for the further clarification when you said:

“When I said that “What is not disputed…” I was referring to the initial twelve-way division under Diocletian, and most importantly, the purpose for the division. During the Crisis of the third century (from about 234 – 284 A.D.), the empire was going through one emperor about every two years, because everyone kept invading Rome. Diocletian’s solution was to decentralize, remove power from Rome and create four new capitals, making it impossible for someone to take over the empire simply by invading one city. ”

I am trying to figure out if you are referring to a civil authority or an ecclesiastical authority.

I’ve been pouring over the source documents in the 3-vol set entitled Roman State and Christian Church (a collection of legal documents to A.D. 535) and cannot find any references to your opinions above…at least not yet.

I’m not just reading the actual legal documents, but also going over the detailed and extensive footnotes on each mandate, letter or edict source document. The Edict of Milan certainly gives some civil credibility that during that time Milan was a place of meeting, but beyond that I see most of the ecclesiastical decisions (and court documents) being referred to the Bishop of Rome for legal controversy.

I guess there is a distinction to be made as to who had civil authority and who had ecclesiastical authority during this period you are referring to from 293AD to end of fourth century. You must be solely discussing the authority of the State taking civil authority away from Rome and moving it to Milan, and not the authority of the Christian Church.

For example, page 48 in vol. 1 describes the history of the ecclesiastical legal system going back to Acts 15, and even before to 47 bc in Syria. It seems clear that Roman Law was always operated out of Rome, and soon ecclesiastical law would follow once the early Jewish Christians saw the gentiles develop the use of Bishops to govern court decisions out of Rome. Would this legal history conflict with your position?

I guess not if you are only saying that Rev. was written prior to 70AD and the #2 point I made above where I thought you were saying that ecclesiastical authority was shifted from Rome to Milan. That was my misunderstanding. You must be saying that all CIVIL authority was moved to Milan, and the Bishop of Rome retained authority in ecclesiastical matters.

It is NOT until 381 that I see the authority of the Bishop of Rome is taken from him in the Mandate of Gratian, etal, and that is the first time I see he loosing his power.

I don’t see any power moving to Milan except for civil power according to source documents that are legal. However, I’m still looking so I might find something.

Thanks, Walt,

Some additional source documents that may be of interest:

1) Council of Antioch when Paul of Samosota was deposed. The church of Antioch sought help from Cappodocia and from Alexandria, but not from Rome. The matter was finally decided by the Church There, Paul of Samosota was excommunicated, and a new bishop of Antioch placed there. Rome was not consulted in the matter. They were simply informed of the change after the fact. (Eusebius, Church History, Book VII, chapter 30, paragraph 17). When they appealed to Emperor Aurelias because Paul would not leave the Church Building, Aurelius had the decision on the real estate issue remanded to the jurisdiction of the Bishops of Italy and of the City of Rome to determine what to do with the property. The significance is that Italy and the City of Rome were two different ecclesiastical, and two different civil jurisdictions, and they also happened to be where Emperor Aurelius was reigning. The matter was not simply remanded to the Bishop or Rome. (Eusebius, Church History, Book VII, chapter 30, paragraph 19).

2) Council of Arles (314 A.D.): convened to review a decision of the bishop of Rome.

3) Council of Alexandria (324 A.D.), Bishop Hosius presiding, in the dispute over the Arian heresy. Hosius was sent as a representative of Constantine, but when it was not worked out in Alexandria, Constantine convened a council in Nicæa (315 A.D.) where it was resolved. The matter was not referred to Rome.

4) Council of Sardica (343 A.D.), Bishop Hosius presiding. The decision of Julius on the matter of Athanasius is submitted to Judicial review at the request of the two emperors.

5) Canon 9 of Sardica makes it clear that the metropolitan in any province whatsoever may appeal directly to the Imperial Court. But in Italy where there were two metropolitans, so an additional clarification was necessary because it was not so simple as requiring that an appeal go through the Metropolitan. Elsewhere in Italy, the appeal could be made through the Metropolitan, or “in the places or cities in which the most pious Emperor is administering public affairs.” He was administering those affairs from Milan. But if the appeal was made in the city of Rome, that appeal would have to go through Julius. Here is the text of Canon 9. It makes sense in light of the fact that “Italy” and “Rome” were two different jurisdictions:

Can you provide references that show that “most of the ecclesiastical decisions (and court documents) [were] being referred to the Bishop of Rome for legal controversy”? The data above shows that Rome was hardly the first option, or even the end of the process, in ecclesiastical decisions.

Thanks,

Tim

Walt, you wrote,

In the particular context in which you cited me, I was referring to civil authority.

Thanks,

Tim

Tim wrote:

“Witness Calvin:

“In regard to the antiquity of the primacy of the Roman See, there is nothing in favor of its establishment more ancient than the decree of the Council of Nice, by which the first place among the Patriarchs is assigned to the Bishop of Rome, and he is enjoined to take care of the suburban churches.” (Institutes, b. iv., c. 7)

But Nicæa had not said anything in favor of the primacy of the Roman See or assigning it first place. That is something Calvin read into it, not understanding the significance of Diocletian’s reorganization.”

To be clear, many in the historicist reformed camp believe this about Calvin and his views on eschatology (from an historicist Elder I know):

“no, Calvin did not write a commentary on Revelation. Eschatology was definitely not a strong point for him.–this is evident from his misunderstanding of Romans 11, and numerous Old Testament passages in relation to the restoration of the Jews.”

Thus, I would rather you use the other two Ministers I shared a week or so ago to counter their arguments. These appear to be the most current source document references (outside of Scripture) used by Historicist post-mill authors.

Notes on the Apocalypse by David Steele

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/14485/14485-h/14485-h.htm

Lectures upon the Principal Prophecies of the Revelation by Alexander M’Leod.

http://archive.org/stream/lecturesuponprin00mcle/lecturesuponprin00mcle_djvu.txt

Walt, you wrote,

I wasn’t appealing to Calvin for his views on eschatology. As I said, Calvin misread Nicæa because he did not understand Diocletian’s reorganization. I was not appealing to him for his eschatology but to illustrate his factual mistake. Again, here is what I said:

Later this week, I’ll take a look at some of the other sources you provided.

Thanks,

Tim

Tim wrote:

“Can you provide references that show that “most of the ecclesiastical decisions (and court documents) [were] being referred to the Bishop of Rome for legal controversy”?”

Yes, let me work on it. I just started researching this topic today and as I was pouring over these mandates, edicts and letters I could not find much out of Milan, and certainly did find other counsels outside Rome, but that was the nature of the empire. I have to do more research to compile the statements that I’ve been reading.

Tim,

I now recognize you were correcting Calvin on a factual issue, but many do cite Calvin on eschatology trying to prove the “reformers” did not understand eschatology..

So I just implied that one should not source Calvin on eschatology. It was good that Calvin identified correctly the Papacy as Antichrist, as did Knox and Luther.,..as did many of the confessions, general assembly decisions and Covenants.

However, since there was no unity or agreement on the subject of eschatology in the Westminster Assembly it was not further addressed. It was not until later in the second reformation and post second reformation do we see more advanced literature on the subject of eschatology. That is why I gave you what some view are the best references to historic post millennialism so that if you cite reformers on prophecy it would be best to source those two references as “generally” fundamental to historic post millennialialism theories.

Early reformers got the Papacy and Rome right on the mark, similar to some of the early church fathers you have cited that started to see the early marks of antichrist.

By the way, have you found any early fathers who held to your view that Revelations was written prior to 70AD?

Remember, I disagree with you on Rev. 1:1. I don’t believe it says that it will “shortly come to pass” but rather that it “will soon begin to appear in history.”

Tim wrote:

“Some additional source documents that may be of interest:”

Here is another disagreement we have discussed. You cited those council decisions that were regional, and not appealed to Rome. For me, these fit perfectly into the Presbyterial form of church government, rather than the episcopal form or Romish form.

If there was a council decision at a regional or local level, these would be presbyterial, especially if the civil government called for these councils.

“III. Civil magistrates may not assume to themselves the administration of the Word and sacraments; or the power of the keys of the kingdom of heaven;[5] yet he has authority, and it is his duty, to take order that unity and peace be preserved in the Church, that the truth of God be kept pure and entire, that all blasphemies and heresies be suppressed, all corruptions and abuses in worship and discipline prevented or reformed, and all the ordainances of God duly settled, administrated, and observed.[6] For the better effecting whereof, he has power to call synods, to be present at them and to provide that whatsoever is transacted in them be according to the mind of God.[7]”

In prelacy and episcopacy, they would appeal to a King or Pope (as even the church itself describes itself as a church) as their head of the church. Where do you see this in the early church?

In Roman State and Christian Church, I see over and over again the civil government calling for councils and Bishops to establish assemblies to determine and stamp out heresy, and then once the decision is rendered the civil magistrate beginning to implement civil penalties for those heretics to be punished. The ecclesiastical case law suggests that the first step in the process of dealing with heretics was sanction and ultimately excommunication from the “Catholic” or universal church, and then I see these written mandates by these emperors notifying governors, etc. to make the peace in unity.

I’m not sure where you get prelacy out of this model.

Tim wrote:

”

Walt, you wrote,

“I am trying to figure out if you are referring to a civil authority or an ecclesiastical authority.”

In the particular context in which you cited me, I was referring to civil authority.

Thanks,

Tim”

Ok, this is what I was hoping, as this is why I’m using Roman State and Christian Church as the source document. It is the best set of primary source documents establishing the legal foundation of actually what governed the history of the Roman empire and its effect on the Christian church. The source documents don’t allow you to read too much into one’s own presupposition as can happen when one uses books covering the period of history as historical references.

Governments are run by their laws and statutes, and like in our modern age executive orders by the President, while in the Roman empire they were by Mandate, Edict and Letters written by kings and emperors. “The incompetent ruler ironically combines in his name those of Rome’s first king (Romulus, who traditionally reigned 753-716BC) and first emperor (Augustus, who principate was 27BC-AD14)….But the writ of the emperors of the East no longer ran in the West, here their erstwhile subjects were lost by them to the barbarian suzerains, who emitted their own laws (modelled indeed upon Roman law) notably in the three following codes (written in Latin), although which the administration of Roman law survived in Western Europe during the Dark Ages; …. (goes on to detail out the 3 codex ….)

….In the Empire popular legislation soon vanished; first the Assemblies ceded their rights to the Senate and the emperor; then the Senate surrendered its right to the emperor. The last law know to have issued from a Roman Assembly was enacted in Nerva’s reign (96-8), and the Senate passed its last recorded senatusconsult of legislative character in the principate of Probus (276-82).

H.J. Wolff in discussing the imperial legislation rightly remarks that “from Constantine on … The emperors were the masters of the law as they were masters of the Empire … The law had lost its quality of being an integral part of the life of the nation and had become a mere tool in the hands of the authoritarian government … completely dependent on the absolute will of the ruler.” (Roman Law: An Historical Introduction, 90-1).

In short, by the end of Constantine I’s reign (306-37) the Roman Empire was transformed into what surely may be termed a totalitarian state. But, since totalitarianism hardly appears without a cause, what had caused the transformation? Doutless it was the imperial desire of Dicletian (284-305) to inhibit the decay which, having begun after the death of Alexander Severus (222-35), he inherited at his accession. In an abnormal dance of death, within almost 50 years of anarchy (235-84), appeared about thirty legitimate and illegitimate emperiors, of whom only one escaped a violent end…..”

Tim wrote:

“b) More accurately, it is critical to understand the structure of Diocletian’s reorganization in 293 as well as further reorganizations that took place in the fourth century.”

Walt wrote:

“In short, by the end of Constantine I’s reign (306-37) the Roman Empire was transformed into what surely may be termed a totalitarian state. But, since totalitarianism hardly appears without a cause, what had caused the transformation? Doutless it was the imperial desire of Dicletian (284-305) to inhibit the decay which, having begun after the death of Alexander Severus (222-35), he inherited at his accession. In an abnormal dance of death, within almost 50 years of anarchy (235-84), appeared about thirty legitimate and illegitimate emperiors, of whom only one escaped a violent end…..”

So something significant took place legally as we see….

“For the administrative alterations, devised by Dicletian and by Constantine confirmed, and sundry other schemes, started or substituted by succeeding sovereigns, controlled men’s modes of livelihood through hereditary corporations in occupations, expanded the system of enforced public services, tightened taxation for the poor in favor of the rich, assisted agriculture to the injury of industry, so that investment of wealth….”

Tim said:

“b) More accurately, it is critical to understand the structure of Diocletian’s reorganization in 293 as well as further reorganizations that took place in the fourth century.”

Roman State and Christian Church says:

“This collection of legal documents affecting the Christian Church in the Roman Empire is the first of its kind in any language.

“The permanent division of the Empire, when Theodosius I the Great at his death in 395 divided it between his sons, Arcadius in the East and Honorius in the West, created a permanent situation which called for solution: what to do about the validity of legislation enacted by one of the two emperors? This problem presented difficulties, especially when the emperors did not see eye to eye on theological tenets, (18) and was decided in 438 by Theodosius II, who declared that one emperor’s enactments would be invalid in his colleagues realm, unless these first should have been submitted to him and then should have secured his sanctions….”

Tim, you should have used this definition for me…would have helped me get a more simple grasp.

“(a) The emperors recognized the eccleasiastical organization as observed in dioceses (which patriarchs or exarchs ruled), provinces (over which metropolitans or archbishops or primates presided), and cities (where bishops supervised the lower clergy). (42) Legislation pertaining to ordination and to consecration as well as to the hierarchy’s jurisdiction and to relative rank within it was enacted, with the result that the episcopate not only was strengthened at the expense of the inferior clergy, but also was subjected to the mercy of the State.

(42) Care must be taken to distinguish between ancient and modern uses of these terms. While the classical meanings of these words are explained in the Glossary, it is not inappropriate to note here that among the Diocletian-Constantinian (284-337) administrative reforms was a coalescense of provinces into a larger territorial unit called a diocese: thus the civil diocese of Hispania (Spain) contained seven provinces (listed in no. 19, n.27). But in modern times an ecclesiastical province contains several dioceses….”

Hey Bob, I just saw a short clip by Hal Lindsey who said that God just spoke to him that things are getting really serious, and soon Antichrist will appear…as he has been saying since the 1980s.

Check with John Wesley as I think he will be looking for Antichrist in the future too.

WALT–

John Wesley has already passed on. Do you not read your history? The future has already come and gone for him.

Found this quote…Bob, wake up soon please! Wesley got something right…I’m so delighted to say.

My father is Methodist and does not believe John Wesley called the Papacy Antichrist. The video does not show a book referenced on Part 2 of the video for the John Wesley quote. Please help I want my father to see it for himself in the book written by John Wesley. It will carry more weight when we watch the video together and I can show him the proof after.

Yes Wesley did indeed believe that the papacy was the antichrist and he taught that the beast of Revelation 13 was also the “Romish Papacy” He also wrote that the “Babylonish woman of Revelation 17 is the papal city, likewise “Antichrist, the man of sin.” the references are:

1) John Wesley, Explanatory Notes Upon the New Testament, p. 290 296 v.1-5

2) John Wesley, Explanatory Notes Upon the New Testament, p.313, v3; p. 316, v. 11

WALT–

I am not here to defend the Methodists. Methodists really do not need defending. This blog by Tim is very anti-Catholic and so are you. I am just taking their side. Your stix and stonz do not effect me. Or haven’t you noticed that? Are you awake?

Bob wrote:

“WALT–

I am not here to defend the Methodists. Methodists really do not need defending. This blog by Tim is very anti-Catholic and so are you. I am just taking their side. ”

Geez Bob, I think Tim does a very admirable job allowing you Catholics and Catholic apologists a voice on this blog. You should be very thankful that us Protestants let you guys voice your hatred of truth and purity, while it is an absolute fact that even simple challenges on most Roman Catholic blogs are refused. I’ve posted on several and with only basic questions was removed and blocked.

It is incredible to see how anti-Calvinist and anti-Protestant the Roman Catholic community is in history, even to the point of hunting and murdering Christians. See Fox Book of Martyrs for a systematic listing of all the Christians murdered by Rome. It is incredible how evil your Roman Catholic apologies talk about “anti-Catholic” standard smoke and mirrors, and ignore the millions and millions of Christian murdered by the Roman Catholic Church and her system of wickedness.

What is really politically positive for you and Jim is to march around the blogosphere and label those of us who have left the Roman Catholic church as “anti-Catholic” but ignore the fact that we hate the system which is anti-christ. I feel really sorry for you, Jim, CK and the billion+ Roman Catholics who are brain washed in the system.

I wish you guys would all leave that terrible system that has murdered millions of Christians, and are perfectly defined as anti-christ and anti-protestant. We are only testifying against anti-christ which is our duty. Sometimes you Catholic apologists get in the cross fire do to your defending Satan and his daughters.

Walt,

Was your Methodist father the one who forced you to be a Catholic altar boy and ring the little bell at Mass which traumatized you so much you later left the Church?

Why didn’t you join your dad’s Methodist denomination?

JIM–

I know how you hate the words “hocus pocus”.

The etymology of the phrase is very interesting, though. It makes sense that it is a bastardized “hoc est corpus” meaning “this is my body”.

Read on:

http://socrates58.blogspot.com/2008/12/anti-catholic-cultural-remnants-hokey.html

Walt,

When did the apostate romish church, with it lying prophet and Eucharistic sores of stigmata decide to start suppressing the doctrines of positive reprobation, limited atonement, once-saved-always-saved and penal substitution? Shortly before 350 A.D.? Immediately after? Who were some of the chief architects in the new merit system and revival of works? When did the whore suppress the doctrines of grace and put people back under the law? Exactly which power hungry Bishop of Rome implemented the idea that Christ suffered the torments of the damned in the stead of the elect?

How did they pull it off with no one the wiser? Tim hasn’t accounted for how the entire romish empire went along like sheep in having the gospel stolen right out from under their noses without uttering a peep.

So, your position is that from 350 A.D. until the time of John Knox introducing the Deformation to Scotland, the world lay under the thralldom of the harlot, yes?

Without copy and pasting tomes that I haven’t the patience to plod through, could you, in your own words, please explain the beliefs you so tenaciously cling to?

I mean, you do actually have some positive ideas or beliefs, don’t you? You don’t just denounce the harlot, right?

Would you be willing to articulate some, nay, just one thing you believe in?

Tim,

No fair putting words in Walt’s mouth. He is a big boy, a confirmed Calvinist and outspoken hater of the Church so he should be able to utter something with that charming brogue he has affected.

Walt,

OOPS! OOPS! OOPS!

I said, “Exactly which power hungry Bishop of Rome implemented the idea that Christ suffered the torments of the damned in the stead of the elect?”

I meant to ask which one “suppressed” this doctrine until it was revived by Calvin?

This is Podcast, 13 Horns.

you said this:

Reading Daniel 7 in this light, the little horn appears in the last days of the Roman Empire, but Daniel is not talking about the little horn ruling over the other horns, but about the persecution of the saints until the fourth beast in his body was killed, destroyed, and given over to the burning flame (Daniel 7:11). Rather, what we see is a little horn growing into its final role while small compared to the other horns in Daniel 7:8, and then becoming equal to the other horns in power, (Revelation 17:12), and then becoming stronger than its fellows (Daniel 7:20), and then the other horns surrendering their power and authority to it (Revelation 17:13). We see the little horn increase in size, strength and influence until it finally takes its dominion and exercises its satanic power and authority over the world.

perfect. Maybe im confused but i try the figure out when the Roman Empire or the fourth Beast, would disappear. This must have been occured before Anti-Christ arose? or in the same time?

or Tim, i ask in this manner, when did that happen in history?:

the fourth beast in his body was killed, destroyed, and given over to the burning flame

The transition from 4th Beast to the 5th Beast is not like previous transitions. Babylon is conquered by the Medo-Persians. The Medo-Persian empire is conquered by the Greeks. The Greek empire devolves into four horns that are eventually subsumed under the empire of the 4th Beast when Rome transitions from Republic to Empire under Julius Cæsar. There are definite transitions as one empire falls and the next takes over.

But if you read Daniel 2 & 7 and Revelation 13 carefully, that is not the case with the transition from the 4th Beast to the 5th Beast which is the Little Horn of Daniel 7, the Sea Beast of Revelation 13.

Remember, the 4th Empire had toes (Daniel 2), and the 4th Beast had horns (Daniel 7). Those horns, including the Little Horn, are Roman Horns and live on long after the “body” of the Beast is destroyed, and remain as equals with the Little Horn, and then hand their power over to him, and then are finally aggregated for battle against the Lord when He returns.

Daniel saw the Little Horn rise from among the other horns and “continued watching” until the “body” of the 4th Beast was destroyed. The body was destroyed, but the beast and its rising horns tell a chronological tale (just as with the Ram, which had two horns and the larger horn came up last). The Body (the last remnants of unified Roman empire) was destroyed, but it had been replaced by Horns at the insistence of Diocletian in the late 200s, and that transition from body to horns took place from around 293 AD (when Diocletian began the reorganization) to about 273 AD when the final 13-way division took place. That was the time the little horn began to rise and claim 3 horns as its own at least by 382 by Pope Damasus after the Council of Constantinople (381 AD) claimed that Constantinople was the New Rome.

So, reading Daniel 7:11, we can see that the “body” of the Roman Empire would not die immediately before the rise of the Little Horn, but clearly some time after, and even so, the Roman elements of the empire (the horns or toes) continue until the Lord’s return, when they will be aggregated by the Little Horn for battle:

After the Roman body is destroyed, it is clear that its Roman horns/toes live on. My point is simply that we should not expect the Roman Empire to fall away and disappear with the rise of the Little Horn. Rather, the Little Horn simply adapts itself to the Roman Empire, which is why the Roman Catholic empire is not only a continuation of the other beasts (Daniel 7:12) and of the Roman Empire as well (Revelation 13:1-2), but is in fact its means of longevity. It survives because of the rise of Roman Catholicism. This is why Roman Catholic apologists think that the “kingdom given to the saints” in Daniel 7:27 is the Roman Empire being given to Roman Catholicism.

More on this later. My only point here is that we ought not look for an end to the Roman Empire as the necessary condition for the Rise of the Little Horn, because the Scriptures do not indicate that to be the case. In fact they indicate that the life of the Beast continues for a while even after the rise of the Little Horn. And they also indicate that the Roman constituent parts of the Roman Empire (horns and toes) go on until the end.

Tim, THANK YOU.

Great, that you take always the time to answer.

I asked about the script (which you used for your podcast “Antiochus and the abomination of desolation Part 1”)

Is it possible to get that?

If yes, i will send you again an email, so that you can send it to me.

If not, dont worry. Im still happy to hear the podcasts!

” which is why the Roman Catholic empire is not only a continuation of the other beasts and of the Roman Empire as well, but is in fact in means of longevity, it survives because of the rise of Roman Catholicism. This is why Roman Catholic apologists think ” kingdom given to the saints” in Daniel 7:27 is the Roman Empire being given to Roman Catholicism.” So Roman Catholicism received the embodiment of all that was evil and sinful and human about those empires , becomes the living extension and embodiment of them, yet portrays itself as receiving the God’s kingdom. I think we need to understand that the people in Roman Catholicism are certainly under this delusion. One 17th century theologian said no sane man could look at Roman Catholicism and not see that it is a front for the kingdom of Satan. Yet apart from God revealing that to his elect, those others are under this allusion. I really appreciate Tim you have cleared the forest so they can see. We should pray everyday the elect would here his call to come out from Rome, and those who are blind are given sight.