In the last two weeks, we have laid the foundation for an analysis of the Seventieth Week of Daniel. In The Leviticus 26 Protocol, we showed that the Seventy Weeks of Daniel 9 are inextricably related to the Seventy Year chastisement described in Jeremiah 25 and 29. The latter chastisement (Seventy Weeks of Years) is a seven-fold prolongation of the former chastisement (Seventy Years) and thus, the Weeks and Years must in some way share a common point of beginning. In our follow up article, Rightly Dividing the Weeks, we showed that Gabriel, in explaining the vision to Daniel, divided the Seventy Weeks into three subsets—the Sixty-two, the Seven and the One. The Seven Weeks (587 – 538 B.C.) ran concurrently with the Sixty-two (605 – 171 B.C.), which was only possible if Gabriel had first “divided” the Weeks, which is precisely what he did when he announced them to Daniel. That is why the “anointed” is described as being “cut off” after the Sixty-two Weeks (Daniel 9:26), rather than after the often alleged, but Scripturally untenable, “Sixty-nine.”

What follows upon the description of the Sixty-two Weeks is the most detailed description of any Week in the ninth chapter of Daniel. What we will demonstrate is that the Seventieth Week of Daniel was fulfilled between 171 and 164 B.C., in the period of Greek rule over Israel. As we shall also demonstrate, Jesus acknowledged the past fulfillment of Daniel’s Seventieth Week when He instructed His audience in Matthew 24:15 and Mark 13:14 to watch carefully for the soon return of the Abomination of Desolation to the Holy Land.

“And he shall confirm the covenant with many…”

As we noted last week, Onias III was the High Priest of Israel, but when King Antiochus IV came to power in Syria in 175 B.C., Onias’ brother Jason purchased the High Priesthood from the king for 32,000 pounds of silver (2 Maccabees 4:7-8). He may have purchased the title, but he could not purchase the anointing, which remained with Onias, the legitimate High Priest.

Jason was of an irreligious faction that desired to secularize the Jewish people. When he became High Priest in 175 B.C., his aim was to abandon the Jewish rites that separated the Jews from the Gentiles, and bring the Jews into conformity with gentile practices. We might say that Jason was a politician, and secularization was his platform. His plans for secularization are related in the apocryphal book, 1 Maccabees, which depicts a time of great distress for Israel:

“In those days lawless men came forth from Israel, and misled many, saying, ‘Let us go and make a covenant with the Gentiles round about us, for since we separated from them many evils have come upon us.’ This proposal pleased them, and some of the people eagerly went to the king. He authorized them to observe the ordinances of the Gentiles.” (1 Maccabees 1:10-13)

The details of the covenant of secularization are described in 2 Maccabees:

“In addition to this [purchasing the priesthood] he promised to pay one hundred and fifty more [talents of silver] if permission were given to establish by his authority a gymnasium and a body of youth for it, and to enrol the men of Jerusalem as citizens of Antioch. When the king assented and Jason came to office, he at once shifted his countrymen over to the Greek way of life. … and he destroyed the lawful ways of living and introduced new customs contrary to the law. For with alacrity he founded a gymnasium right under the citadel, and he induced the noblest of the young men to wear the Greek hat. There was such an extreme of Hellenization and increase in the adoption of foreign ways because of the surpassing wickedness of Jason, who was ungodly and no high priest…” (2 Maccabees 4:9-13)

It seems that many of the Jews had had enough of the “perpetual desolations” (Jeremiah 25:12), and wanted to walk away. Jason was just the politician who could lead them into secularization. As noted above, “this proposal pleased them,” and many converted “eagerly” to the Greek way of life. The old religion was tolerated, but the vast majority had decided to become Greeks. And thus in 175 B.C. did “the many” enter into a covenant with the king of Syria to adopt the ways of the Gentiles.

But for some in Israel, Jason’s policies were not sufficiently phil-Hellenic, which is to say that Jason had not gone far enough in his secularization program. What the people needed for an enduring secularization was someone truly committed to the cause, someone of the Tobiad party which was truly invested in absolute secularization. That someone was Menelaus, and his objective was to do away with the old religion entirely.

As noted above, Jason had usurped the legitimate High Priest Onias III by offering money to the king, and what was good for Jason’s goose was also good for Menelaus’ gander. Menelaus simply approached King Antiochus with a better offer, and Antiochus could do nothing else than respect the chutzpah of such a man. He accepted the higher offer, made Menelaus High Priest, and essentially made Jason into a fugitive, just as Onias III had been before him:

“But he, when presented to the king, extolled him with an air of authority, and secured the high priesthood for himself, outbidding Jason by three hundred talents of silver. After receiving the king’s orders he returned, possessing no qualification for the high priesthood, but having the hot temper of a cruel tyrant and the rage of a savage wild beast. So Jason, who after supplanting his own brother was supplanted by another man, was driven as a fugitive into the land of Ammon.” (2 Maccabees 4:23-26)

This created even more strife in an already tense situation, some people siding with Jason’s more moderate secularization policies, and some siding with Menelaus and his more fierce, more extreme secularization. The phil-Hellenic Tobiad party of course sided with Menelaus, and repaired to King Antiochus to seek his blessing for Menelaus to complete the secularization program that Jason had started. The men even went so far as to reverse their circumcision surgically:

“And the sons of Tobias took the part of Menelaus, but the greater part of the people assisted Jason; and by that means Menelaus and the sons of Tobias were distressed, and retired to Antiochus, and informed him that they were desirous to leave the laws of their country, and the Jewish way of living according to them, and to follow the king’s laws, and the Grecian way of living. Wherefore they desired his permission to build them a Gymnasium at Jerusalem. And when he had given them leave, they also hid the circumcision of their genitals, that even when they were naked they might appear to be Greeks. Accordingly, they left off all the customs that belonged to their own country, and imitated the practices of the other nations.” (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book XII, Chapter 5, paragraph 1)

It was under Menelaus that the covenant with King Antiochus IV reached its fullest expression; it was under Menelaus that the Jews truly separated themselves from their religious past, and Menelaus began to do what Jason had not even imagined: he began to sell off the articles of the temple (2 Maccabees 4:32).

The legitimate High Priest Onias III had stood by and watched Jason take away his High Priesthood, but he could not stand idly by as the articles of the sanctuary were profaned. But it was too late, and Menelaus arranged for Onias to be assassinated in order to silence the opposition:

“When Onias became fully aware of these acts he publicly exposed them, having first withdrawn to a place of sanctuary at Daphne near Antioch. Therefore Menelaus, taking Andronicus aside, urged him to kill Onias. Andronicus came to Onias, and resorting to treachery offered him sworn pledges and gave him his right hand, and in spite of his suspicion persuaded Onias to come out from the place of sanctuary; then, with no regard for justice, he immediately put him out of the way.” (2 Maccabees 4:33-34)

Thus, what Antiochus IV had started in the usurpation of Onias in 175 B.C when he covenanted with the Jews to become Greeks, he completed by affirming Menelaus’ more extreme secularization policies in the usurpation of Jason in 171—the same year Onias III was murdered. In fact, we might even say that in his elevation of Menelaus to replace Jason, Antiochus IV had strengthened the covenant that he had earlier made with the Jews to adopt the Greek way of life.

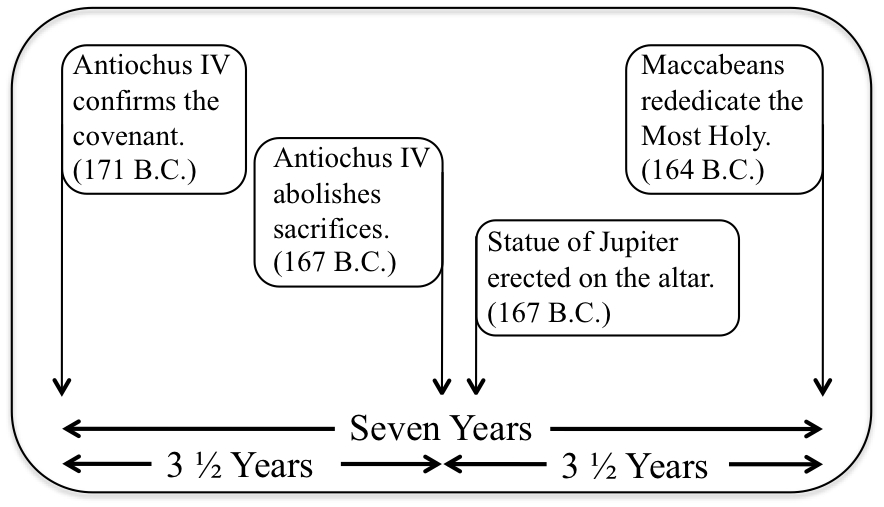

We highlight that word, strengthened, for a reason. Daniel 9:26-27 informs us that “the prince that shall come … shall confirm the covenant with many for one week.” The wording here does not suggest the making of a covenant, but the strengthening of one that is already in place. The word rendered as “confirm” in Daniel 9:27 is the Hebrew word, gabar, which means to strengthen, to make stronger (see Zechariah 10:6, 12). King Antiochus IV had accepted the help of Jason in 175 B.C. to commit the Jewish people to a Greek way of life. Then Menelaus usurped Jason, and in 171 B.C., the same year Onias III was murdered, Antiochus IV strengthened that commitment when the Tobiad party met with him, confirming the agreement, or covenant, that had been in place since 175. 171 B.C., therefore, is the beginning of the One Week.

Often, in the eschatologist’s haste to find Christ in the prophecy of Daniel 9, he will assume that the “he” in Daniel 9:27 refers to Christ, as in “Christ shall confirm the covenant with many for one week…”. What is incorrectly assumed is that the “covenant” that “he” “confirmed” is that which Christ confirmed in His death, i.e., by “the blood of the covenant” (Hebrews 10:29). However, the “he” in Daniel 9:27 is “the prince” of the previous verse, who “shall come” and “shall destroy the city and the sanctuary” (Daniel 9:26). That “prince” refers to Antiochus IV, not to Christ. Christ did not come to destroy the city and the sanctuary during His earthly ministry, and neither did He come to enter into a seven year covenant with His people. His covenant is everlasting (Hebrews 13:20). Antiochus IV is that prince who was to come, and his strengthened covenant, as we shall see, only lasted “One Week.”

“…he shall cause the sacrifice and the oblation to cease…”

This portion of the prophecy of Daniel 9:27—that “he” shall cause sacrifice to “cease”—is typically read in a Christological context that is foreign to the text, as if the only possible way for sacrifices to be interrupted is by the arrival of the Messiah. That reading is based on Hebrews 10:18, “Now where remission of these is, there is no more offering for sin.” We agree that Christ put an end to sacrifices for sins. However, the context of Daniel 9:27 is not that of a Protagonist Who cancels our debts, but of an antagonist who abolishes lawful sacrifices under the old covenant and desolates the sanctuary in the process.

Antiochus IV is known to have conducted two expeditions against Egypt—one in 170 B.C. and one in 168 B.C.. It is the second expedition that is of interest to us here. The Senate of Rome was alarmed at his expansionist policy, and sent Gaius Popilius Laenas as an envoy to put an end to Antiochus IV’s invasion of Egypt. This interference by Rome in Antiochus’ plans has been preserved in the vernacular of the west by the term “line in the sand.” When Gaius Popilius confronted Antiochus and demanded that he obey the decree of the Senate, Antiochus responded that he must first consult with his advisors and determine what to do. That is when Popilius drew a circle around him in the sand, and insisted that Antiochus inform him of his decision before stepping out of it. To do anything but capitulate would have been an act of war against Rome, something Antiochus was not prepared to do. He therefore gave in to Rome’s demands (Livius, History of Rome, Book 45, 12; Polybius, The Histories, Fragments of Book XXIX, I.2). The confrontation between Antiochus and Popilius is dated to July 168 B.C. (Alan K. Bowman, Egypt after the Pharaohs, University of California Press (1996) 31-32).

Still stinging from his humiliation in Egypt, Antiochus returned to Jerusalem in the 145th year of the kingdom of the Greeks (1 Maccabees 1:29), which is 167 B.C.. It was then that he implemented a harsh policy of persecution against the Jews, as recorded for us in 1 Maccabees 1:30-40:

“… he suddenly fell upon the city, dealt it a severe blow, and destroyed many people of Israel. He plundered the city, burned it with fire, and tore down its houses and its surrounding walls. And they took captive the women and children, and seized the cattle. Then they fortified the city of David with a great strong wall and strong towers, and it became their citadel. And they stationed there a sinful people, lawless men. These strengthened their position; they stored up arms and food, and collecting the spoils of Jerusalem they stored them there, and became a great snare. It became an ambush against the sanctuary, an evil adversary of Israel continually. On every side of the sanctuary they shed innocent blood; they even defiled the sanctuary. Because of them the residents of Jerusalem fled; she became a dwelling of strangers; she became strange to her offspring, and her children forsook her. Her sanctuary became desolate as a desert; her feasts were turned into mourning, her sabbaths into a reproach, her honor into contempt. Her dishonor now grew as great as her glory; her exaltation was turned into mourning.” (1 Maccabees 1:30-40)

After competing the sack and occupation of Jerusalem, Antiochus published a decree that formally abolished the sacrifices and oblations of the altar:

“Then the king wrote to his whole kingdom that all should be one people, and that each should give up his customs. … And the king sent letters by messengers to Jerusalem and the cities of Judah; he directed them to follow customs strange to the land, to forbid burnt offerings and sacrifices and drink offerings in the sanctuary, to profane sabbaths and feasts, to defile the sanctuary and the priests…” (1 Maccabees 1:41-46)

Thus did Antiochus IV abolish sacrifices and oblations in 167 B.C., half way through the Seventieth Week. As Josephus reports, Antiochus IV “spoiled the temple, and put a stop to the constant practice of offering a daily sacrifice of expiation for three years and six months” (Flavius Josephus, Wars of the Jews, Book I, Chapter 1, paragraph 1).

Regarding the prohibition of sacrifices, Josephus appears to waver between a three and a half year period (as in Wars of the Jews, cited above) and a three year period. For example, in Antiquities of the Jews, he writes that Daniel prophesied that Antiochus “should spoil the temple, and forbid the sacrifices to be offered for three years’ time” (Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book X, chapter 11, paragraph 7). The inconsistency is likely due to the fact that 1 Maccabees reports that the Statue of Jupiter had defiled the temple for exactly three years to the day (1 Maccabees 1:54, 4:52-54). Yet the way 1 Maccabees 1:41-53 describes the prohibition of sacrifices, the actual decree to prohibit the sacrifices is described as a separate event prior to the erection of the idol, apparently taking place earlier the same year. Thus in Wars, Josephus seems to identify a three and a half year period during which sacrifices were prohibited by decree, and within that period, three years during which sacrifices were impossible due to the presence of the abomination on the altar. He confirms this reading later in Antiquities (Book XII, chapter 7, paragraph 6).

The Abomination of Desolation

As the narration continues, in the winter of 167 B.C., Antiochus erected the “desolating sacrilege” on the altar in Jerusalem:

“Now on the fifteenth day of Chislev, in the one hundred and forty-fifth year, they erected a desolating sacrilege upon the altar of burnt offering…” (1 Maccabees 1:54)

The identity of the “desolating sacrilege” may be known by the response of the Samaritans to the sack of Jerusalem. Lest they, too, come under the wrath of Antiochus, the Samaritans appealed to him that their temple, too, be dedicated to Jupiter. Their epistle to Antiochus, and his written response to their request, is recorded for us in Josephus’ Antiquities of the Jews:

“To king Antiochus the god, Epiphanes, a memorial from the Sidonians, who live at Shechem. Our forefathers, upon certain frequent plagues, and as following a certain ancient superstition, had a custom of observing that day which by the Jews is called the Sabbath. And when they had erected a temple at the mountain called Gerrizzim, though without a name, they offered upon it the proper sacrifices. Now, upon the just treatment of these wicked Jews, those that manage their affairs, supposing that we were of kin to them, and practiced as they do, make us liable to the same accusations, although we be originally Sidonians, as is evident from the public records. We therefore beseech thee, our benefactor and Savior, to give order to Apollonius, the governor of this part of the country, and to Nicanor, the procurator of thy affairs, to give us no disturbance, nor to lay to our charge what the Jews are accused for, since we are aliens from their nation, and from their customs; but let our temple, which at present hath no name at all be named the Temple of Jupiter Hellenius. If this were once done, we should be no longer disturbed, but should be more intent on our own occupation with quietness, and so bring in a greater revenue to thee.” (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book XII, chapter 5, paragraph 5)

To these overtures, King Antiochus IV responded amicably:

“King Antiochus to Nicanor. The Sidonians, who live at Shechem, have sent me the memorial enclosed. When therefore we were advising with our friends about it, the messengers sent by them represented to us that they are no way concerned with accusations which belong to the Jews, but choose to live after the customs of the Greeks. Accordingly, we declare them free from such accusations, and order that, agreeable to their petition, their temple be named the Temple of Jupiter Hellenius.” (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book XII, chapter 5, paragraph 5)

Thus do we identify the Statue of Jupiter as the Abomination of Desolation that was foretold by Daniel the prophet.

Notably, 2 Maccabees, which was written much later and in some places revises the history of 1 Maccabees, identifies the abomination of desolation as “Olympian Zeus” (2 Maccabees 6:2). This is probably due to the authors’ recognition that Antiochus IV was Greek, and therefore ought to have dedicated the temple to the Greek Zeus rather than to the Roman Jupiter. However, Antiochus IV was raised in Rome for thirteen years prior to coming to Syria to succeed his father there. A condition of the Treaty of Apamea after Antiochus III’s defeat in 188 B.C., was that his son, Antiochus IV, must remain permanently in Rome as a hostage (Appian, History of Rome, the Syrian Wars, chapter 39; see also 1 Maccabees 1:10). Antiochus had spent much of his youth in Rome, exposed predominantly to Roman culture.

That said, it would make little sense for the Samaritans to request that their temple be dedicated to Jupiter Hellenes in imitation of the Jews dedicating the Temple to Olympian Zeus. Clearly the Jewish Temple had been dedicated to Jupiter. In any case, because Livius records that Antiochus IV dedicated his temples to Jupiter—one in Athens to Olympian Jupiter, and another in Antioch to Capitoline Jupiter (Livius, Periochae, Book 41, 5-6), we defer here to Josephus’ account, since he is actually citing written communications between the Samaritans and Antiochus IV, and all acknowledged, with Livius, that Jupiter, not Zeus, was the object of Antiochus’ devotion.

“…and to anoint the most Holy”

Fortunately, despite the extreme persecution of the Jews, there yet remained a remnant that did not adopt the new policies of Antiochus IV. They refused to sacrifice to false gods, refused to profane the Sabbath, refused to stop circumcising their sons, and refused to give up the Scriptures. This is the period of the Maccabean revolt, when Judas Maccabeus and his brethren took the Temple back. The episode is cited in its entirety from 1 Maccabees:

“Then said Judas and his brothers, ‘Behold, our enemies are crushed; let us go up to cleanse the sanctuary and dedicate it.’ So all the army assembled and they went up to Mount Zion. And they saw the sanctuary desolate, the altar profaned, and the gates burned. In the courts they saw bushes sprung up as in a thicket, or as on one of the mountains. They saw also the chambers of the priests in ruins. Then they rent their clothes, and mourned with great lamentation, and sprinkled themselves with ashes. They fell face down on the ground, and sounded the signal on the trumpets, and cried out to Heaven. Then Judas detailed men to fight against those in the citadel until he had cleansed the sanctuary. He chose blameless priests devoted to the law, and they cleansed the sanctuary and removed the defiled stones to an unclean place. They deliberated what to do about the altar of burnt offering, which had been profaned. And they thought it best to tear it down, lest it bring reproach upon them, for the Gentiles had defiled it. So they tore down the altar, and stored the stones in a convenient place on the temple hill until there should come a prophet to tell what to do with them. Then they took unhewn stones, as the law directs, and built a new altar like the former one. They also rebuilt the sanctuary and the interior of the temple, and consecrated the courts. They made new holy vessels, and brought the lampstand, the altar of incense, and the table into the temple.Then they burned incense on the altar and lighted the lamps on the lampstand, and these gave light in the temple.They placed the bread on the table and hung up the curtains. Thus they finished all the work they had undertaken. Early in the morning on the twenty-fifth day of the ninth month, which is the month of Chislev, in the one hundred and forty-eighth year, they rose and offered sacrifice, as the law directs, on the new altar of burnt offering which they had built. At the very season and on the very day that the Gentiles had profaned it, it was dedicated with songs and harps and lutes and cymbals. All the people fell on their faces and worshiped and blessed Heaven, who had prospered them. So they celebrated the dedication of the altar for eight days, and offered burnt offerings with gladness; they offered a sacrifice of deliverance and praise. They decorated the front of the temple with golden crowns and small shields; they restored the gates and the chambers for the priests, and furnished them with doors. There was very great gladness among the people, and the reproach of the Gentiles was removed.” (1 Maccabees 4:36-58)

Three and a half years after sacrifices were abolished, and three years to the day since the abomination of desolation was erected on the altar, the sacrifices of the Law of Moses were restored.

At this point we will simply highlight the fact that the altar, the sanctuary and the holy vessels were all rebuilt by “blameless priests devoted to the law.” That law required the newly constructed “altar most holy,” and the sanctuary and vessels to be anointed when they were first consecrated for holy use:

“And thou shalt take the anointing oil, and anoint the tabernacle, and all that is therein, and shalt hallow it, and all the vessels thereof: and it shall be holy. And thou shalt anoint the altar of the burnt offering, and all his vessels, and sanctify the altar: and it shall be an altar most holy. And thou shalt anoint the laver and his foot, and sanctify it.” (Exodus 40:9-11)

Thus was the Most Holy anointed at the conclusion of the Seventy Weeks, just as Gabriel had prophesied. The anniversary of that celebration is now known as Hanukkah, the Feast of the Dedication of the Temple, as mentioned in John 10:22, “And it was at Jerusalem the feast of the dedication, and it was winter.”

Conclusion on the Seventy Weeks

By way of summary, we recall from last week that from the going forth of God’s promise to rebuild Jerusalem (587 B.C.) to the coming of Cyrus, an “anointed ruler” (538 B.C.), was Seven Weeks. From the original beginning of the Seventy Year chastisement (605 B.C.) to the “anointed” High Priest Onias III being murdered (171 B.C.) was Sixty-two Weeks. From the strengthening of the covenant for the Jews to adopt the Greek way of life (171 B.C.) to the anointing of the Sanctuary, the Altar and all the Holy Vessels (164 B.C.) was One Week. As we noted last week, the Seventy Weeks were “divided” into three sets of Weeks, and each set concluded with either an anointed ruler (Cyrus), or an anointed high priest (Onias III), or a literal anointing of “the Most Holy,” the the altar of the burnt offering. None of these “anointeds” or “Most Holy” were referring to Christ, and all of the Weeks were fulfilled during the period that spanned the transition from the Medo-Persian and Greek empires, reaching their conclusion and the culmination of the Maccabean Revolt when the Most Holy was rededicated in 164 B.C..

“When ye therefore shall see the abomination of desolation…”

To what, then was Jesus referring when He warned of a future and visible appearance of the Abomination of Desolation? One of the most difficult traditions to overcome in eschatology is the belief that Jesus placed the Seventieth Week of Daniel 9 in His own immediate or distant future. This tradition is based on His reference to the Abomination in two verses from the gospels of Matthew and Mark:

“When ye therefore shall see the abomination of desolation, spoken of by Daniel the prophet, stand in the holy place, (whoso readeth, let him understand:)” (Matthew 24:15)

“But when ye shall see the abomination of desolation, spoken of by Daniel the prophet, standing where it ought not, (let him that readeth understand) … :” (Mark 13:14)

From these verses, two traditions have emerged, neither of which is supported by the text. First, that the Seventieth Week of Daniel had not yet occurred at the time of Christ, and second, that Jesus expected the abomination to be erected in the Temple in Jerusalem. These traditions have caused us to translate and interpret Matthew 24:15 and Mark 13:14 as if they were referring to a future fulfillment of Daniel 9:26-27.

Based on these traditions, the eyes of Christian eschatologists have been ever fixed upon the Temple in Jerusalem, awaiting the inevitable arrival of the Seventieth Week when the Abomination of Desolation would be placed there. In other words, Matthew 24:15 and Mark 13:14 are interpreted to mean,

“When Daniel’s words are finally fulfilled during the Seventieth Week and the Abomination of Desolation is finally placed in the Temple in Jerusalem, (let him that readeth understand)…”

But that is not what Jesus said. When Jesus said “let him that readeth understand,” what is to be read is Daniel’s prophecy. In the reading of Daniel’s prophecy, we can understand that the Abomination of Desolation was a Statue of Jupiter. In Jesus’ day, those who read Daniel already understood that the Statue of Jupiter was the Abomination of Desolation. From the writings of the Maccabees in the centuries before Christ, to the writings of Flavius Josephus in the first century, it was understood that Daniel’s prophecy of the Abomination of Desolation referred to a Statue of Jupiter:

“…they erected a desolating sacrilege upon the altar of burnt offering…” (1 Maccabees 1:54)

“… they had torn down the abomination which he [Antiochus IV] had erected upon the altar in Jerusalem…” (1 Maccabees 6:7)

“And indeed it so came to pass, that our nation suffered these things under Antiochus Epiphanes, according to Daniel’s vision, and what he wrote many years before they came to pass.” (Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book X, chapter 11, paragraph 7)

The Jews of Jesus’ day would have recognized that the Abomination of Desolation—a statue of Jupiter—had been placed in the Temple in 167 B.C. in fulfillment of Daniel’s vision.

It is also noteworthy that Jesus does not actually refer to the temple in Matthew 24:15. What is translated as “the holy place,” lacks in Greek the definite article, “the,” or τὸν, as in “ἐν τὸν τόπῳ ἁγίῳ.” What is recorded for us in Matthew 24:15 is instead, “ἐν τόπῳ ἁγίῳ.” Lacking that definite article, Matthew 24:15 is more properly rendered,

“When ye therefore shall see the abomination of desolation, spoken of by Daniel the prophet, stand in a holy place, (whoso readeth, let him understand:)”

or

“When ye therefore shall see the abomination of desolation, spoken of by Daniel the prophet, standing on holy ground, (whoso readeth, let him understand:)”

In other words, neither Matthew nor Mark renders Jesus’ words as “the Holy Place,” or “Holy of Holies” or “the Sanctuary” or “the Temple.” By way of comparison, see Hebrews 8:2, 9:1, 2, 3, 8, 12, 24, 25, 10:19, 13:11, where the reference is clearly to the Temple. Or see Acts 6:13 (“this holy place”) and Acts 21:28 (“this holy place”) where the pronoun “this” is not lacking in the Greek. Yet the weight of tradition has caused most translations to render Matthew 24:15 as if Jesus was referring to a future fulfillment of Daniel 9 by the placing of the Abomination in the Holy Place. But Jesus’ warning was simply that the Abomination of Desolation would return and stand where it ought not be, in a place that is considered holy.

Tradition aside, we must instead defer to what the text actually says. On that note, all of Israel is holy to the Lord (Zechariah 2:12), and all of Israel is a place where an idol ought not be. In fact, the stated objective of the Hebrews’ occupation of the Holy Land was to drive out the people and their idols:

“Speak unto the children of Israel, and say unto them, When ye are passed over Jordan into the land of Canaan; Then ye shall drive out all the inhabitants of the land from before you, and destroy all their pictures, and destroy all their molten images, and quite pluck down all their high places:” (Numbers 33:51-52).

When Matthew and Mark tell us of Jesus’ warning, and He refers to “a holy place” where an idol “ought not” be, such a description encompasses all of Israel, and is not limited to the Temple grounds. The significance to our present discussion is that within a decade of Jesus’ death and resurrection, the Abomination of Desolation was back on holy ground, in Israel, where it “ought not” be. The Statue of Jupiter had returned.

Gaius Caligula’s Edict

Emperor Caligula, as is well known, was obsessed with his own deification, and routinely modified statues of Jupiter, replacing Jupiter’s head with his own. Seutonius writes of this practice, and the fact that Caligula desired to be addressed, and worshiped, as Jupiter:

“…he began from that time on to lay claim to divine majesty; for after giving orders that such statues of the gods as were especially famous for their sanctity or their artistic merit, including that of Jupiter of Olympia, should be brought from Greece, in order to remove their heads and put his own in their place, he built out a part of the Palace as far as the Forum, and … exhibited himself there to be worshipped by those who presented themselves; and some hailed him as Jupiter Latiaris. He also set up a special temple to his own godhead, with priests and with victims of the choicest kind. In this temple was a life-sized statue of the emperor in gold, which was dressed each day in clothing such as he wore himself.” (Seutonius, Life of Caligula, 22)

Some of his devotees, hearing “how exceedingly eager and earnest Gaius is about his own deification,” deliberately provoked the Jews in Israel by erecting an altar to him in Jamnia. They obtained the desired reaction, and the Jews destroyed the altar. In response to this insult, Caligula ordered that a large statue of himself “in the character of Jupiter” be erected in Jerusalem (Philo, On the Embassy to Gaius Caligula, XXX, XXXV).

As Josephus reports, Caligula commissioned Publius Petronius, governor of Syria, “to place his statues in the temple,” and on his orders, “Petronius marched out of Antioch into Judea” with the statues and “with three legions” of soldiers. The Jews were deeply disturbed at the news, and went out to meet him at Ptolemais, begging him not to do it. “So he was prevailed upon by the multitude of the supplicants, and by their supplications, and left his army and the statues at Ptolemais, and then went forward into Galilee” to convince the Jews to comply with Caligula’s edict (Flavius Josephus, Wars of the Jews, Book II, chapter 10, paragraphs 1-3).

Additionally, some zealots in Dor on the coast to the south of Ptolemais, in anticipation of Caligula’s decree, had already “carried a statue of Caesar into a synagogue of the Jews, and erected it there” (Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book XIX, Chapter 6, paragraph 3).

Ptolemais is the ancient city of Acre. Acre and Dor, as described in Judges 1:27-32, were among the places from which the tribes of Asher and Manasseh were supposed to have driven out the peoples with their idols, but had not:

““Neither did Manasseh drive out … the inhabitants of Dor and her towns, … Neither did Asher drive out the inhabitants of Accho…” (Judges 1:27-32)

We simply note here that according to Zechariah 2:12, Accho and Dor—being a part of the promised land—were holy to the Lord, and according to Numbers 33:51-52, Accho and Dor were both places where an idol “ought not” be. The arrival of the statues of Caligula in the form of Jupiter, standing on holy ground (Matthew 24:15), where they should not be (Mark 13:14), is the very event of which Jesus had warned.

Caligula died before his statues of Jupiter could be erected in the Temple in Jerusalem, but not before they had arrived in Israel. Thus, by 40 A.D., the Abomination of Desolation of which Daniel had spoken—which abomination had been placed on the altar in 167 B.C.—was back in Israel, less than ten years after Jesus’ warning.

After the statues of Jupiter had arrived in the Holy Land, the situation there deteriorated rapidly. Bandits, false messiahs and miracle workers roamed the land. Famine, chaos and violence were the order of the day, setting the stage for the final confrontation between Rome and Jerusalem:

“Under the series of governors who followed, the situation sharply deteriorated. … Ferocious armed adventurers and self-styled prophets and holy men roamed round the land more or less unchecked, and insurrections with a religious or political coloring, or both, broke out in many regions. The procurator Tiberius Julius Alexander (46-48), a renegade Jew, had to deal with a major famine… The tenure of Ventidius Cumanus (48-52) witnessed riots, a massacre in the Temple, and clashes between Samaritans and Galileans. The next governor, Antonius Felix (52-60), enjoyed lofty connections both at the court of the emperor Nero (54-68) and among the Jews themselves. Nevertheless, his vigorous efforts to restore order only produced a higher level of violence, and Judaea was once again filled with armed bands of freedom-fighters and miracle workers, proclaiming a heady mixture of nationalistic and revolutionary and messianic slogans. In particular, a group of urban terrorists became an increasingly dangerous menace in Jerusalem itself.” (Michael Grant, The History of Ancient Israel, (Orion Publishing (2012), chapter 20: the Road to Rebellion)

This, of course, is precisely that of which Christ had warned in Matthew 24 and Mark 13. The return of the Abomination of Desolation—the Statue of Jupiter—would be the herald that signaled the beginning of the end for Israel:

“For there shall arise false Christs, and false prophets, and shall shew great signs and wonders; insomuch that, if it were possible, they shall deceive the very elect. Behold, I have told you before.” (Matthew 24:24-25; c.f., Mark 13:22-23)

Thus, what Jesus said in Matthew 24:15 and Mark 13:14—which has historically and traditionally been interpreted as a reference to the future fulfillment of Daniel’s Seventieth Week—is in reality an acknowledgement of the fact that Daniel’s Seventieth Week had already passed. Having already passed, that Seventieth Week served to identify for Jesus’ listeners the Abomination of which Daniel had spoken: the Statue of Jupiter. Equipped with that information, the attentive believer would have seen the abomination standing on holy ground, where it “ought not” be, and recognized it as the harbinger of Israel’s demise and Jerusalem’s inevitable destruction.

We recognize that this idea—that Jesus’ words in Matthew 24 and Mark 13 were an acknowledgment that Daniel’s Seventieth Week had already come and gone—will not be well received in evangelical circles. However, Daniel 8:12-13 describes the “transgression of desolation” spoken of by Daniel the prophet as taking place under the rule of a Greek antagonist, before the rise of Rome. Daniel 11:31 describes “the abomination that maketh desolate” taking place in the period of Greek rule, before the rise of Rome. As we have shown in this series, Daniel 9 points to a Greek antagonist, as well. At no point does any New Testament writer identify the Seventieth Week as a future event, and not one New Testament writer identifies Jesus as the fulfillment of the Seventy Weeks. In other words, the belief in a post-Hellenic, Christocentric fulfillment of the Seventy Weeks is but a widely held tradition, nothing more. It is not a teaching of the Scriptures.

We will pick up on this theme next week and will focus on the fact that Daniel 8 speaks of a Little Horn as a Greek antagonist, while Daniel 7 speaks of a Little Horn as a Roman one. An understanding of the Seventy Weeks of Daniel 9 is critical to the necessary separation of those two antagonists into their respective periods—the reign of Antiochus IV in the 2nd century B.C., and the rise of Roman Catholicism toward the end of the 4th century A.D..

Ironically, Roman Catholics and Historicists have historically shared the view that the Little Horn of Daniel 8 is the same as the Little Horn of Daniel 7. Roman Catholic apologists leverage that identification to make the Little Horn of Daniel 7 into a Greek antagonist, and thus divert our attention away from the Roman Papacy as the Little Horn of Daniel 7 (see Fr. William Most’s, Commentary on Daniel). But many Historicists engage in the opposite error, and try to make the Little Horn of Daniel 8 into a Roman antagonist, and thus have led us to expect in Antichrist certain behaviors, attributes and timelines that belong to the Greek antagonist alone. Both parties, by conflating the two “Little Horns” of Daniel 8 and 7, end up obscuring the identity of Antichrist.

Follow

Follow

This reminds me of the old Hardy Boys episodes in the 1950s.

Actually, it’s a lot like reading “Prophecy in the News” by JR Church and Gary Stearman.

Well, now that I think about it, it’s more like reading http://www.daniels70weeks.com

But who’s paying any attention anyway, right?

“That “prince” refers to Antiochus IV, not to Christ. Christ did not come to destroy the city and the sanctuary during His earthly ministry,”

This is making a lot of sense. Thx for explaining the Scriptures so methodically and clearly Tim.

This is an excellent example of sola scriptura. Thx again Tim.

Hi Tim Kauffman!

Could you in short explain the fullfillment of this?

Daniel 9: and sixty and two weeks: the broad place hath been built again, and the rampart, even in the distress of the times.

what does that mean and how can i explain it to others.

Many people say that, if we take this prophecy not about the messiah, this verse would be false.

Hi, Alessandro,

You may want to revisit Rightly Dividing the Weeks. There we discuss the necessity of the 62-week period beginning at 605 BC:

Daniel 9:25 refers to streets and walls being rebuilt. Ezra and Nehemiah refer to those events. Can you provide some details about why some people think that it cannot be fulfilled unless it refers to the Christ?

Thanks,

Tim

thank you.

yes i will come back to that. i will study their arguements and then come back to you if its not clear.