As we have noted in this series, from the earliest days of the Church through the end of the 4th century, the Eucharist was a thank offering to the Lord, a tithe, an expression of gratitude for the Lord’s provisions to His people. It was followed by an “Amen” (1 Corinthians 14:16) and then bread and wine were taken from the tithe offering to be consecrated for the Lord’s Supper. That Consecration came to be called “the Epiclesis,” or invocation. And thus, a very simple liturgy prevailed for three hundred years: A Eucharist. An Amen. An Epiclesis. But by the end of the 4th century, the order was changed and the Epiclesis was moved before the Eucharist, turning a simple tithe offering into a sacrifice of consecrated bread and wine. Thus was born the abominable Roman Catholic liturgical sacrifice of Christ’s body and blood, an offering utterly foreign to the Scriptures and the Apostolic Church. That sudden 4th-century shift in the liturgy puzzled and confounded scholars, historians, translators and apologists who could not explain why the early liturgy was so different from the medieval one. So the rewriting of history began, and the academic community participated in a painstaking campaign to establish retroactive continuity. Early liturgies were translated, edited, reinterpreted, mistranslated and even rewritten to “correct” the ancient writers and force them into conformity with the late 4th-century novelty. The effect has been to give the appearance that the ancient Eucharist offering was itself the Consecration, essentially collapsing the Eucharist into the Epiclesis.

Last week we reviewed the liturgies of Tertullian of Carthage (208 A.D.), Origen of Alexandria (248 A.D.) and his disciple, Firmilian of Cæsarea (256 A.D.). This week, we pick up with Cornelius of Rome (250 A.D.), Cyprian of Carthage (253 A.D.) and Dionysius of Alexandria (256 A.D.). We find in these writings evidence for the ancient Dismissal, the Eucharistic thank offering followed by an “Amen,” and a Consecration. This is consistent with the Eucharist and Supper of the early centuries, but entirely inconsistent with the Roman Catholic Eucharistic offering of consecrated bread and wine. And thus in the same data we also find the intractable appetite of the scholars and translators for rewriting and reinterpreting the early liturgies to collapse the ancient Eucharist into the Epiclesis to lend Apostolic credibility to Rome’s novel and abominable sacrifice. As we have cautioned before, the task of literary archæology is tiresome, boring and tedious, but it is important for the Christian to understand how the scholars have handled the evidence and succumbed to the sheer force of academic inertia to present to us a version of history that is not only a lie, but is in fact an abomination.

Cornelius of Rome (250 A.D.)

During the persecutions of the third century, Christians were being forced to choose between idolatrous sacrifices or a martyr’s death. In many cases, the flesh prevailed, and a very large number of professing Christians chose the former. When the persecution subsided, those who had lapsed in the faith desired to be readmitted to the Church, but this presented a puzzle, both spiritual and administrative (Cyprian of Carthage, Epistle 39, 3). If the Lapsed were readmitted unconditionally, it opened a door for the unrepentant and unbelieving to enter the Church. But if the Lapsed were treated too harshly, there was the potential to leave the truly repentant believer outside the Church. The bishops of various provinces had taken a middle course, and from this decision arose the two related schisms: Novatian (a.k.a. Novatus) in Rome thought the decision too lax and would not receive the Lapsed at all (Cyprian of Carthage, Epistle 51, 22), and Felicissimus of Carthage thought the decision too severe, and received the Lapsed unconditionally (Cyprian of Carthage, Epistle 39, paragraph 5). In both cities the schism created significant challenges to the bishops, but our focus is on the city of Rome, for it is through this controversy that bishop Cornelius documented his Eucharistic liturgy.

In Rome, lawfully elected Cornelius was struggling to contain the damage from Novatus and wrote to Bishop Fabian of Antioch about his troubles. Novatus had become so invested in the schism that he was actually using the sacred liturgy as a tool to secure the loyalty of his followers and draw men away from Cornelius. We pick up with Eusebius’ account of Cornelius’ letter to Fabian:

[Cornelius] adds to these yet another, the worst of [Novatian’s] offenses, as follows: “For when he has made the offerings, and distributed a part to each man, as he gives it he compels the wretched man to swear in place of the blessing. Holding his hands in both of his own, he will not release him until he has sworn in this manner (for I will give his own words): ‘Swear to me by the body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ that you will never forsake me and turn to Cornelius.’ And the unhappy man does not taste until he has called down imprecations on himself; and instead of saying ‘Amen,’ as he takes the bread, he says, ‘I will never return to Cornelius.'” (Eusebius, Church History, Book 6, 43.18-19)

Cornelius has paid little attention to sequence, focusing first on the defiance of Novatus and second on the impropriety of his hapless loyalist. He describes Novatus giving the bread into the man’s hands after he had already “distributed” it, and describes the communicant “taking” the bread after he has already “tasted” it. Obviously, chronology was not at the fore. The liturgy thus obscured, the translator assumed the communicant’s words “I will never return (ανηξω) to Cornelius” were his response to Novatus’ demand, “Swear to me … that you will never forsake me and turn (ἐπιστρέφαι) to Cornelius” (Migne P.G. vol 20 col 628). But the Greek does not bear that out.

The communicant’s word, “ανηξω (anexo)” is the future tense of “ανηκω (aneco)” which simply means “consistent,” “fitting,” or “appropriate” when used as an adjective, as in Ephesians 5:4, Colossians 3:18 and Philemon 1:8. When used as a verb, as it clearly is in this brief, four-word sentence—”Οὐκέτι ὰνήξω πρός Κορνήλιον”—it means “will belong.” The communicant had not said, “I will never return to Cornelius,” but rather, “I will no longer belong to Cornelius.”

Likewise, Novatus’ word, “ἐπιστρέφαι (epistrephai)” is not the Greek word for “turn,” but rather “return.” When the prefix, “ἐπι-,” is added to “στρεφαι” it becomes “ἐπιστρέφαι” or “return.” Novatus had not said, “Swear to me … that you will never … turn (στρέφαι) to Cornelius,” but rather, “Swear to me … that you will never … return (ἐπιστρέφαι) to Cornelius.”

The translator, thinking Novatus had spoken first and the communicant had responded to him, changed the words “return” into “turn,” and “belong” into “return” in an attempt to make sense of it. Such an errant translation produces the impression that the communicant had “called down imprecations on himself” by the words “I will never return to Cornelius” after the “Consecration.” When translated properly, it becomes clear that he merely stated, “I will no longer belong to Cornelius,” and then, upon Novatus’ insistence, imprecated himself by swearing “by the body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ” that he would never return to him.

This order of events is easily proven by observing the movement of the bread as the liturgy unfolds. Novatus performs the offerings and then distributes the bread. Rather than saying “Amen,” the communicant, as he takes (λαμβάνοντα, lit. seizes (Migne, P.G. 20, 628)) the bread into his hands, utters “I will no longer belong to Cornelius.” Then Novatus, having given the bread, but still holding the recipient’s hands “in both of his own,” instead of pronouncing the Consecration, demands the communicant swear “by the body and blood” never to return to Cornelius. The communicant then imprecates himself by swearing the required oath and then “tastes” the bread. Obviously, Novatus could not restrain the communicant with both hands unless he had already distributed (διανέμων (Migne, P.G. 20, 625)) the bread to him. Thus, by following the transit of the bread from Novatus to the communicant, it is clear that the illicit “Amen” came immediately following “the offerings” and the illicit Consecration followed after the bread was already in the hands of the communicant. A Eucharist. An Amen. An Epiclesis. The same order we saw in the Didache, Justin Martyr, Irenæus and Hippolytus, we now see with Cornelius, and indeed was still practiced by Cornelius’ contemporary, Dionysius of Alexandria, as we will discuss below.

That this is the correct understanding is evidenced further by the fact that even Roman Catholic Migne acknowledged that the communicant’s illicit “Amen” had indeed followed the offerings and preceded Novatus’ illicit “Consecration”:

“Αντί τοῦ εἰπεῖν … Αμεν” — Hoc est quod paulo ante dixit Cornelius “αντι του ευλογειν”

“Instead of saying … Amen” — This is a little before Cornelius said “in place of the blessing”

(Migne, P.G. 20, col 627, n53).

Clearly, Cornelius had no problem with Novatus’ authentic biblical liturgical order, and only complained that Novatus had substituted inappropriate words for the “Amen” and the “Consecration.” Novatus had not changed the order. The order was Apostolic and unaltered. Novatus had only corrupted the substance.

Migne, however, unable to appreciate the significance of the ancient liturgy, assumed that Novatus must have corrupted the order by placing the “Amen” before the Consecration instead of after it. To reassure the reader, Migne added additional explanations indicating that, of course, in a valid liturgy, the “Amen” would follow the Consecration, as evidenced by Ambrose of Milan (On the Mysteries 54 (389 A.D.)), Cyril of Jerusalem (Catechetical Lectures 23 21 (350 A.D.)) and Augustine of Hippo (Contra Faustum, XII.10 (405 A.D.)) (Migne, P.G. 20, 628 (n53)). We note, by way of reminder, that Migne here did what so many before and after him have done, which is to correct the ancient liturgy by assuming that the liturgy of the late-4th century was normative.

Migne was not finished. In the same footnote, in which he tried to explain away the Apostolic “Amen” that occurred between the Eucharist and the Consecration, he tried again to show that in a correctly ordered liturgy, the “Amen” really ought to be spoken immediately after the Consecration. He wrote,

Sæpius autem fideles inter missarum solemnia dicebant Amen. Nam et cum sacerdos panem et vinum consecraret, respondebant Amen, ut pluribus dicitur infra ad caput 9, lib [VII] … (Migne, P.G. 20, 628 (n53)

Moreover, it was customary for the faithful to say Amen during the Mass. For example, when the priest would consecrate the bread and wine, they would respond, Amen, about which more below in Book [VII], chapter 9…

In his reference to Book VII, Chapter 9 of Church History, Migne refers to the liturgy of Dionysius of Alexandria who described “the giving of thanks (εὐχαριστίας)” followed by a corporate “Amen” (Eusebius, Church History, Book VII, chapter 9.4; Migne, P.L. vol 5, col 98). Note that Migne, attempting to prove that the “Amen” is supposed to follow the Consecration refers to Dionysius’ liturgy in which the “Amen” follows the Eucharist. By assuming that the Amen spoken after the Eucharist (in Book VII, 9.4) is the Amen that is spoken after the priest “consecrate[s] the bread and wine” (as in Ambrose (389 A.D.), Cyril (350 A.D.) and Augustine (405 A.D.)), Migne thus assumed that Dionysius’ Eucharist was consecratory. From that assumption he then concludes that Cornelius’ uncorrupted liturgy would have placed the Amen after the Consecration—essentially assuming that both Cornelius’ and Dionysius’ Eucharists were consecratory.

Here Migne has done precisely what we have been highlighting throughout this series. Because the ancient Apostolic liturgy of a Eucharist, an Amen and an Epiclesis is so strangely different from the late-4th century and medieval liturgy of an Epiclesis, a Eucharist and an Amen, the scholars and translators are positively baffled. Migne is thus forced to reinterpret Cornelius’ ancient liturgy through a late-4th century and medieval lens (Ambrose, Cyril and Augustine), and then collapse the offerings into the Epiclesis such that Cornelius’ “Amen” appears to be spoken after “the offerings” of consecrated bread and wine instead of between the Eucharist and the Consecration. In short, Migne attempts to reconcile the ancient liturgy with the medieval novelty by collapsing Cornelius’ Eucharist into his Epiclesis.

Cyprian of Carthage (253 A.D.)

Cyprian of Carthage understood the sacrifices of the church to be sacrifices of praise and thanks, providing for the widow, the orphan and the poor. He cited the Malachi 1:10-11 prophecy to show that “in every place odours of incense are offered to My Name, and a pure sacrifice” by the Church. He also cited Psalms 50:14, “Offer to God the sacrifice of praise, and pay your vows to the Most High,” Psalms 5:23, “The sacrifice of praise shall glorify me,” and Psalms 4:5, “Sacrifice the sacrifice of righteousness” (Cyprian of Carthage, Treatise XII, Testimonies Against the Jews, Book I, chapter 16).

He also criticized the rich for ignoring the wants of the poor and the needy, and for coming to the Lord’s Supper without a sacrifice:

But you … do not see the needy and poor. You are wealthy and rich, and do you think that you celebrate the Lord’s Supper, not at all considering the offering, who come to the Lord’s Supper without a sacrifice, and yet take part of the sacrifice which the poor man has offered? (Cyprian of Carthage, Treatise VIII On Works and Alms, 15)

His reference to coming to the Supper “without a sacrifice” is a reference to the offertory before the Supper. In the same paragraph he reminds the rich that “everything that is given is conferred upon widows and orphans” (Treatise VIII On Works and Alms, 15).

In Treatise IV On the Lord’s Prayer, he writes in the same vein, invoking Philippians 4:18 and the sweet smelling sacrifice of Epaphroditus:

The blessed Apostle Paul, when aided in the necessity of affliction by his brethren, said that good works which are performed are sacrifices to God. “I am full,” says he, “having received of Epaphroditus the things which were sent from you, an odour of a sweet smell, a sacrifice acceptable, well pleasing to God.” For when one has pity on the poor, he lends to God; and he who gives to the least gives to God — sacrifices spiritually to God an odour of a sweet smell. (Treatise IV On the Lord’s Prayer 33)

In the same treatise, he hints at the Dismissal, the point in the liturgy when the unbeliever, the backslider and the catechumen are dismissed before the offertory. He wrote that “[o]ur peace and brotherly agreement is the greater sacrifice to God,” for “God does not receive the sacrifice of a person who is in disagreement” (Treatise IV On the Lord’s Prayer 23). In Treatise III On the Lapsed, he again hints at the Dismissal as he relates the story of an infant who had been, unbeknownst to her mother, compelled to offer sacrifices to false gods. In ignorance her mother brought her in “when we were sacrificing,” and again, another unconverted woman “secretly crept in among us when we were sacrificing” (Cyprian of Carthage, Treatise III On the Lapsed, 25-26). In all these cases he was describing the Eucharist offering that took place immediately following the Dismissal, and prior to the Consecration for the Supper. It was the sacrifice of the Dismissal, or in Latin, the “oblationem missa“, and in its English equivalent, the Sacrifice of the Mass. The tithe offering. It was not an offering of consecrated bread and wine.

That Cyprian understood the Eucharist to be the tithe offering is evidenced by his reference to the fact that the anointing of the newly baptized is performed with oil from the Eucharist:

Further, it is the Eucharist (Eucharistia) whence the baptized are anointed with the oil sanctified on the altar. But he cannot sanctify the creature of oil, who has neither an altar nor a church (Cyprian of Carthage, Epistle 69, 2; for the original Latin, see S. Caecilii Cypriani Carthaginiensis Episcopi, Lucae Friederici Reinharti, ed. (Nürnberg: Henrici Meyers (1681) 189)

In this, his 69th Epistle, like Firmilian in the 74th (of which we spoke in our previous post), Cyprian was responding to bishop Stephen’s claim that heretical baptisms ought to be recognized if they were administered using the correct formula. He criticized “they who assert that heretics can baptize,” and his focus, like Firmilian’s, was that a heretic baptized by a heretic could not have affirmed the truth—a prerequisite for baptism—and therefore neither the baptizer nor the baptized were qualified to participate in the Eucharist offerings that followed: “whence also there can be no spiritual anointing among heretics, since it is manifest that the oil cannot be sanctified nor the Eucharist celebrated at all among them” (Cyprian of Carthage, Epistle 69, 2). It was in the Eucharist that the oil was offered and sanctified, and if the heretic cannot celebrate the Eucharist, then he cannot sanctify the oil, and therefore the baptized could not be anointed with sanctified oil. To Cyprian, the attempt to legitimize the baptism of heretics was a fool’s errand, because the heretic has no means of offering oil in the Eucharist. The presence of oil on the altar as part of the Eucharist in the context of baptism and the Dismissal is sufficient to show that in these references, “the Eucharist” does not refer to the Lord’s Supper.

By way of reminder, the Didache 13 describes the offering of oil: “So also when you open a jar … of oil, take the first-fruit and give it to the prophets.” Hippolytus, too: “If someone makes an offering of oil, the bishop shall give thanks …” (Anaphora, 5). As he noted,

At the time determined for baptism, the bishop shall give thanks over some oil, which he puts in a vessel. It is called the Oil of Thanksgiving. … Afterward, when they have come up out of the water, they shall be anointed by the elder with the Oil of Thanksgiving, saying, ‘I anoint you with holy oil in the name of Jesus Christ.’ (Hippolytus, Anaphora, 21). “

Clearly, oil was included in the Eucharist offerings and used for anointing the baptized, and certainly was not included with the Lord’s Supper. Cyprian has merely acknowledged this fact of history in his 69th Epistle.

It is also true that Cyprian used the term “Eucharist” to refer to consecrated bread and wine. For example, in Epistle 10, Cyprian complains that bishops who give the Eucharist to the unrepentant “profane the sacred body of the Lord” (Epistle 10, 1). We point this out because it is important to understand first that Cyprian used the term to refer both to the unconsecrated elements of the tithe offering and the consecrated elements of the Supper, and second that both the offering and the consecrated elements were holy—not just to Cyprian but to the whole ancient Church. Irenæus, after all, wrote that the offerings became “heavenly” the moment they were set aside as a tithe offering, as we demonstrated in Part 2, and Tertullian referred to the “Amen” spoken over the “holy” offerings as we showed in Part 3. And from this, though Cyprian makes neither an obvious reference to the Apostolic “Amen” nor an explicit reference to an Epiclesis, we can see that he nevertheless divides his liturgy into two distinct parts: the Eucharist offering of unconsecrated food, and the Eucharist Supper of consecrated bread and wine. This, too, is consistent with the liturgy of the ancient Church.

Nevertheless, the translators and historians have taken upon themselves the task of collapsing Cyprian’s Eucharist offering into his Epiclesis to give the impression that he believed the sacrifice of the Church was an offering of the body and blood of Christ. To do so, they have edited his Treatise 3, “On the Lapsed,” and translated his 62nd Epistle, to force upon him an offering of the body and blood of Christ.

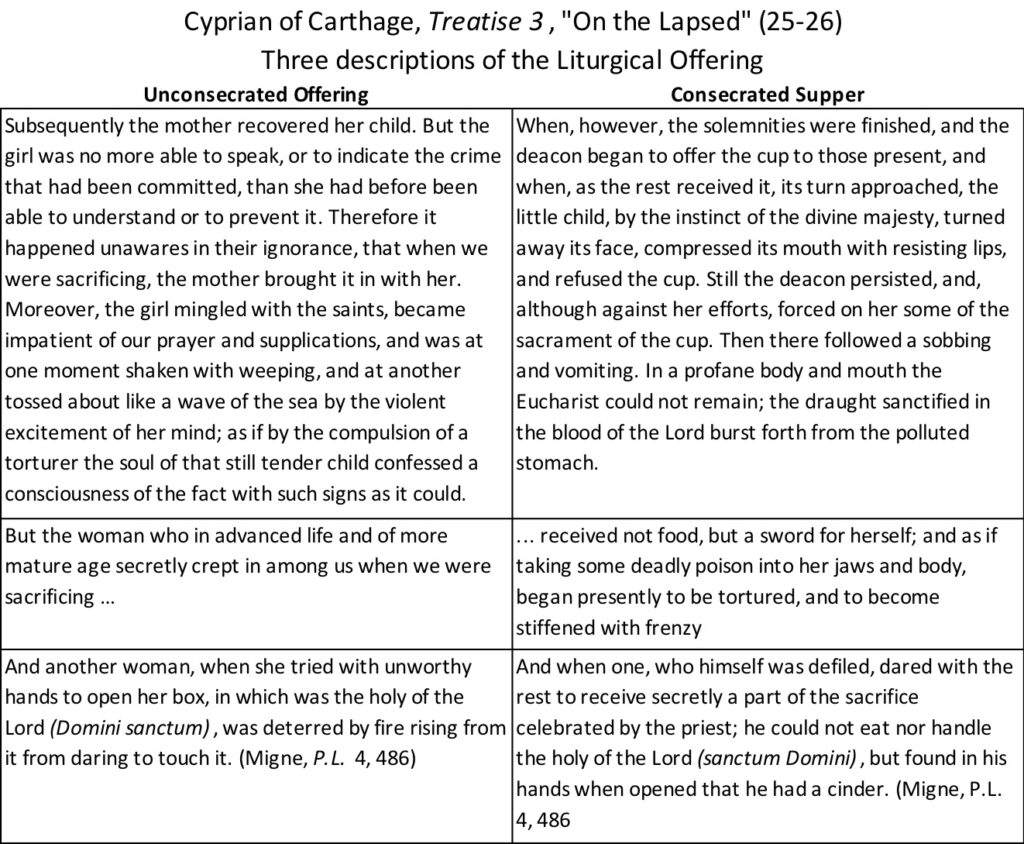

- Treatise 3, on The Lapsed, 25-26

As we have noted above, in his treatise “On the Lapsed,” Cyprian observed that on multiple occasions the unrepentant Lapsed had ignored the Dismissal and remained to participate in the Eucharist and the Supper. In paragraphs 25 and 26 he provided three example of such an offense, and three times he describes the impropriety of the unrepentant Lapsed participating in the sacrifices, followed by the impropriety of the unrepentant Lapsed receiving the consecrated elements of the Supper. We provide the three examples in tabular form below. As the reader examines the table, it will be valuable to recall Hippolytus’ admonition: “Those who are to be baptized are not to bring any vessel, only that which each brings for the eucharist” (Anaphora, 20) as well as Cyprian’s criticism of the rich for coming to church without an offering. It was common to attend church with a container for your offerings, and to contribute to the poor with the rest of the assembly. It was the Eucharist offering. It was the tithe.

Let us now proceed to Cyprian’s three examples. In each case, Cyprian describes the “sacrifices” (shown in the left column) and then the Supper (shown in the right). We invite the particular attention of the reader to the woman in the third example. She had brought a box with her, a plain reference to the vessel containing her the tithe, but unrepentant of her lapse of faith, she was (so Cyprian believed) supernaturally prevented from offering.

Not only are Cyprian’s examples intended to illustrate the problem of the Lapsed disregarding the Dismissal (e.g., to creep in secretly), but also to show that the presence of the Lapsed was inappropriate both for the sacrifices (e.g., prayers, supplications and tithes) and for the Supper (e.g., eating the Eucharist). Each example involves someone inappropriately present for the sacrifices, and someone inappropriately participating in the Supper. These events all occurred during the liturgy, during a church service, as is plainly obvious from the context of his Treatise.

We highlight the third example because, although Cyprian does not identify what “the holy of the Lord” is, it is obvious in context that the first occurrence—”the holy of the Lord” (Domini sanctum) contained in the box—is the holy offering, the box being the vessel in which the tithe was brought to Church, and the second occurrence—”the holy of the Lord” (sanctum Domini) in the mouth—is bread taken from the offerings, consecrated, and administered as the body of Christ. Cyprian uses a similar term for both, just as he did with “the Eucharist,” but context leaves no doubt. The lapsed woman had brought unconsecrated bread to church in a vessel and was unable to offer it, and the lapsed man who thought “to receive secretly a part of the sacrifice” received consecrated bread but was unable to consume it. Thus, the complete narrative is easily, and justifiably understood to mean:

And another woman, when she tried with unworthy hands to open her box, in which was the holy [offering] of the Lord, was deterred by fire rising from it from daring to touch it. And when one, who himself was defiled, dared with the rest to receive secretly a part of the sacrifice celebrated by the priest; he could not eat nor handle the holy [body] of the Lord, but found in his hands when opened that he had a cinder.

The words “offering” and “body” are not present in the Latin text, but are easily inferred from the immediate context of Cyprian’s letter, and from the broader context of the early liturgy.

So what did the translators do? They assumed instead that the first occurrence was a reference to consecrated bread. Roman Catholic Migne added a footnote indicating that Domini sanctum in the woman’s container must be a reference to “corporis Christi,” the body of Christ. Here he assumed the woman had left the service after the consecration and carried the bread home with her, just as the woman of Tertullian’s Ad Uxorem, Book II, chapter 5 (Migne, P.L. 4, 486n). There is, of course, nothing in the text to suggest either that she had opened her box after the consecration or that she had even departed from the church service before opening it. The context of Cyprian’s three examples has her doing this during the offerings after ignoring the Dismissal. Anglican translator Robert Ernest Wallis, for his part, took it further by simply inserting “body” into the text to give the impression that the woman had consecrated bread in her box, giving the impression that Christ’s body is what was being offered in the sacrifices:

“And another woman, when she tried with unworthy hands to open her box, in which was the holy (body) of the Lord… (Cyprian of Carthage, Treatise 3, 26; Robert Ernest Wallis (Anglican), trans. From Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. 5. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1886.) See this rendering here.)

The woman, of course, had neither brought consecrated bread with her to church in a box, nor had she left the church with consecrated bread in her container. She had carried a tithe to church in her box, and was supernaturally prevented (according to Cyprian’s interpretation) from offering. However, an apostolic, Biblical representation of the Eucharist offerings cannot be allowed to stand, so the Roman Catholic, with a footnote, and Anglican translator, with an editorial modification to the text, essentially collapse Cyprian’s Eucharist into his Epiclesis, giving the false impression that the Cyprian’s Eucharistic offerings consisted of consecrated bread and wine.

- Epistle 62, on the Sacrament of the Cup of the Lord, 9

During the persecutions of the 3rd century, the faithful were being detected by the red wine they had consumed for the Supper. To avoid detection and martyrdom, some professing Christians were using water alone in the Eucharist. Cyprian was aghast, and wrote his 62nd Epistle to correct the practice: “the cup of the Lord is not indeed water alone, nor wine alone … just as, on the other hand, the body of the Lord cannot be flour alone or water alone” (Epistle 62, 13). The cup could no more be water without wine than the bread could be water without flour. Because the Eucharist as a meal must answer to Christ’s passion, the Eucharist as an offering had to include actual wine—else there would be no wine from the Eucharist to use for the Supper. Therefore “our oblation and sacrifice [must] respond to His passion” (Epistle 62, 9). Fair enough.

Much has been made of Cyprian’s statements in this epistle that “the Lord’s passion is the sacrifice which we offer.” We must offer “according to what the Lord offered” and there ought be “no departure from what Christ both taught and did” (Epistle 62, 17). Indeed Cyprian appears to insist that if we would imitate Christ, we must offer “consecrated” bread and wine in our oblations:

“Whence it appears that the blood of Christ is not offered if there be no wine in the cup, nor the Lord’s sacrifice celebrated with a legitimate consecration unless our oblation and sacrifice respond to His passion.” (Epistle 62, 9)

“Thus, therefore, in consecrating the cup of the Lord, water alone cannot be offered, even as wine alone cannot be offered.” (Epistle 62, 9)

If Jesus offered His own blood the night before he died, then it is the duty of the Church to offer what he offered in the Supper, and to do what He did. We must therefore offer consecrated bread and wine, just at the Lord did. At least, that is how the indiscriminate apologist reasons, following the path of least resistance, but the conclusion is without merit when Cyprian is taken in the context of his own words.

It is true that Cyprian insists that “we ought to do nothing else than what He did” (Epistle 62, 17), but in the same epistle Cyprian also acknowledges that Jesus could not have had His own blood in the cup, nor given His own blood to drink, the night before He died:

… just as the drinking of wine cannot be attained to unless the bunch of grapes be first trodden and pressed, so neither could we drink the blood of Christ unless Christ had first been trampled upon and pressed, and had first drunk the cup of which He should also give believers to drink (Epistle 62, 17).

If we cannot “drink the blood of Christ” until after the Crucifixion, then neither could His disciples “drink the blood of Christ” before the Crucifixion. And if they could not “drink the blood of Christ” at the Supper, then “the blood of Christ” is not what Christ had in the cup, and therefore “the blood of Christ” is not what He offered. And since we must “offer” what He “offered,” we do not “offer” the blood of Christ. What we must do, as Cyprian says in this very epistle, is “offer wine in the sacrifices of the Lord” (Epistle 62, 12).

What is more, as we noted above, Cyprian understood Malachi 1:11 to refer to the Eucharist offerings of the Church for the widow, the orphan and the poor. Remarkably, he expounded in great detail on upon the sacrifice of the Church, and even said “peace and brotherly agreement is the greater sacrifice to God” (Treatise IV On the Lord’s Prayer 23). And yet for all of his eloquent exegesis on Malachi 1:11, he omitted any reference to the consecrated bread and wine as the sacrifice that fulfills it (Cyprian of Carthage, Treatise XII, Testimonies Against the Jews, Book I, chapter 16). A remarkable omission indeed if he was convinced that we ought to offer Christ’s body and blood as our sacrifice in fulfillment of Malachi 1:11.

What then did Cyprian mean by “the Lord’s passion is the sacrifice which we offer”? The explanation is quite simple. By his own words, Cyprian reveals to us that “to offer” in this context simply means “to commemorate.” For his understanding of “offering” Cyprian had relied on the ancient Latin rendering of Tobit 12:12, which in Greek is rendered,

“I brought the remembrance of your prayer”

(ἐγὼ προσήγαγον τὸ μνημόσυνον τῆς προσευχῆς)

but in Latin is rendered

“I offered the remembrance of your prayer”

(ego obtuli memoriam orationis)

(See Treatise IV, 33 (Migne, PL, 4 540) and Treatise VII, 10 (Migne, PL, 4 588-89).

Indeed, the immediate context of Cyprian’s statement reveals precisely this meaning:

And because we make mention of His passion in all sacrifices (for the Lord’s passion is the sacrifice which we offer), we ought to do nothing else than what He did. … As often, therefore, as we offer the cup in commemoration of the Lord and of His passion, let us do what it is known the Lord did. (Epistle 62, 17)

Further analysis of Cyprian’s letters reveals this exact use of “offer” to mean “commemoration.” In Cyprian’s mind, “to offer” the passion of a martyr or the good work of a brother was “to celebrate” or “to commemorate” and to memorialize the martyr’s death or the brother’s labors with a sacrificial offering. We “offer sacrifices for them” to “celebrate the[ir] passions … in the annual commemoration” (Epistle 33, 3). On the anniversaries of their deaths “we … celebrate their commemoration among the memorials of the martyrs…; and there are celebrated here by us oblations and sacrifices for their commemorations …” (Epistle 36, 2). The martyr “which affords an example to the brotherhood both of courage and of faith, ought to be offered up when the brethren are present” (Epistle 57, 4). Out of gratitude for the generosity of their brethren, and “in return for their good work,” the needy were encouraged to “present them in your sacrifices and prayers,” and “to remember [them] in your supplications and prayers” (Epistle 59, 4). Contrarily, the brother who died in disobedience would not be so memorialized: “no offering should be made for him, nor any sacrifice be celebrated for his repose” (Epistle 65, 2). All of these illustrate Cyprian’s propensity for conflating “offer” and “commemorate,” implying that he was “offering” in the sacrifices that which he was really only “commemorating” in them, be it the good works of the brethren, the passions of the martyrs on their anniversaries, or the Crucifixion itself. Based on Cyprian’s reading of Tobit, “to offer” the Lord’s passion is simply to “commemorate” it or to “bring it to remembrance” by “mak[ing] mention of His passion” in the sacrifices. He had not actually advocated sacrificing the Lord’s passion at all.

But what of Cyprian’s insistence that the cup of the Lord must be consecrated for the offering, or that we must celebrate the Lord’s sacrifices with a legitimate consecration? That, as it turns out, was the product of the translator’s medieval imagination. Cyprian had not actually written anything about offering the Lord’s sacrifices with a “legitimate consecration” at all.

We know very well from Cyprian that in the Eucharistic tithe offerings, what is “offered” is thereby sanctified, set apart for holy purposes. By way of illustration, in his 69th Epistle, Cyprian refers to the sanctification of the oil in the Eucharist, as we noted above.

Further, it is the Eucharist whence the baptized are anointed with the oil sanctified (sanctificatur) on the altar. But he cannot sanctify (sanctificare) the creature of oil, who has neither an altar nor a church (Cyprian of Carthage, Epistle 69, 2; Reinharti, 189)

Here, “sanctified” simply means set apart for the Lord’s use. Because there is no possible sense in which Cyprian may be alleged to have “consecrated” the oil of the Eucharist, sanctificatur and sanctificare are rendered by the translator exactly as one would expect. In the Eucharist offering the oil is sanctified for holy uses, either to anoint the baptized, as Cyprian mentioned, or to feed the poor as Hippolytus mentioned: “Sanctify this oil … so that it may give strength to all who taste it” (Hippolytus, Anaphora, 5). There is no puzzle, confusion or controversy here. The tithe offerings were “sanctified,” set apart for heavenly uses, just as the bread in Irenæus became “heavenly” simply by being set aside to feed the poor (Against Heresies, Book IV, 18.5). Similarly with the “holy offerings” in Tertullian before the “Amen,” and the Domini sanctum of Cyprian’s Treatise on the Lapsed. The oil had not been “consecrated.” It had been “sanctified.”

That this is Cyprian’s constant use of the term the translators concede by their repeated translation of it:

… by the sanctification (sanctificatione) of baptism, therein put off the old man by the grace of the saving layer …. (Treatise II, “On the Dress of Virgins,” 23; Migne, P.L. 4, 463)

…we who by His sanctification (sanctificatione) have received the Spirit and truth… (Treatise IV, “On the Lord’s Prayer,” 2; Migne PL 4.521)

… for we have need of daily sanctification (sanctificatione), that we who daily fall away may wash out our sins by continual sanctification (sanctificatione). (Treatise IV, “On the Lord’s Prayer,” 12; Migne PL 4.527)

…for those are purged by the blood and sanctification (sancitificatione) of Christ. (Treatise VIII, “On Work and Alms,” 2; Migne PL 4.603)

…to present us to the Father, to whom He has restored us by His sanctification (sanctificatione) (Treatise VIII, “On Work and Alms,” 26; Migne PL 4.621)

…they may all bear the garments of Christ robed in the sanctification (sanctificatione) of heavenly grace. (Treatise XI “Exhortation to Martyrdom,” 3; Migne PL 4.653)

Again, there is no puzzle, confusion or controversy here. We know very well what sanctification means, and we also know very well what Cyprian meant by it, and we know very well that Cyprian used the term to describe what happens to the Eucharist offerings. The oil used to anoint the baptized is “sanctified (sanctificatur)” in the Eucharist. He did not mean “consecrated” and he was not referring to the Lord’s Supper.

Our only hint of what Cyprian could possibly have believed about the consecration must come from Tertullian, his predecessor in that city. Tertullian’s view is of some value because Cyprian “had no Christian writings besides Holy Scripture to study besides those of Tertullian” (Catholic Encyclopedia, Cyprian of Carthage, “Doctrine”). Tertullian believed the bread was consecrated by the recitation of Christ’s words of institution: “He made it His own body, by saying, ‘This is my body'” (Tertullian, Against Marcion, Book IV, 40). We know Cyprian knew of an Epiclesis, since he described the reception of the body of Christ in the Supper, but nowhere in any of his writings do we find an explicit Consecration. Perhaps he adopted Tertullian’s view. We do not know.

Lacking any evidence for an explicit Epiclesis in Cyprian, the translator has taken upon himself the task of creating one for him. When Cyprian speaks of sanctifying the wine in the offering, or celebrating the Lord’s sacrifices with a legitimate sanctification, the translator sets aside the abundant evidence from Cyprian about sanctifying the tithe offerings in the Eucharist, and assumes instead that he must in this case be referring to the Consecration. In Epistle 62, Cyprian merely said that the oblation must be legitimately sanctified, but the translator instead reinterprets it to mean that the oblation must be legitimately consecrated:

Whence it appears that the blood of Christ is not offered if there be no wine in the cup, nor the Lord’s sacrifice celebrated with a legitimate consecration (sanctificatione) unless our oblation and sacrifice respond to His passion. (Epistle 62, 9; (Migne P.L. 4, col 381))

Thus, therefore, in consecrating (sanctificando) the cup of the Lord, water alone cannot be offered, even as wine alone cannot be offered. (Epistle 62, 13; (Migne P.L. 4, col 384)

And again in Epistle 63, in which the context is the greed of a disgraced bishop who had been desirous of the “gifts, and offerings” of the oblation (Epistle 63, 3), the translator cannot resist the temptation, and so translates “sanctified” as “consecrated” to fabricate in Cyprian an Epiclesis by the invocation of the Holy Spirit:

Since neither can the oblation be consecrated (sanctificari) where the Holy Spirit is not; nor can the Lord avail to any one by the prayers and supplications of one who himself has done despite to the Lord. (Epistle 63, 4; Migne P.L. 4, 392)

And thus, with a stroke of the pen, the translator has invented in Cyprian a convenient Epiclesis to make him conform to the medieval liturgy in which the bread and wine are consecrated in the oblation. Where Cyprian clearly believed the bread, wine and oil are sanctified in the offerings and then the bread and wine are consecrated for the Supper, the translator decides to render “sanctified” as “consecrated” to indicate that Cyprian must really have meant that the bread and wine of the offering had been “consecrated.”

The reader will notice how conveniently the translator has included his own thoughts in the mind of Cyprian as he translates him. Christians were known to bring the tithes to the weekly church service in containers, and those tithes were considered to belong to the Lord for His uses—Domini sanctum—yet the translator simply inserts the word “body” to give the impression that the participant had brought consecrated bread with her in order to offer Christ in her sacrifices. And where Cyprian clearly did not believe Jesus had offered His own blood the night before He died, and clearly believed the tithes were sanctified by the Spirit in the Eucharist, the translator decides on Cyprian’s behalf that he must really have meant “consecrated” by invocation of the Spirit in the oblation. In both cases, the translator has attempted to establish retroactive continuity by collapsing Cyprian’s Eucharist into his Epiclesis to give the impression that he believed the sacrifice of the Church the offering of consecrated bread and wine in the Supper.

Dionysius of Alexandria (256 A.D.)

A contemporary of Firmilian of Cæsarea, Cornelius of Rome and Cyprian of Carthage, Dionysius was unsure of what to do about heretical baptisms administered with the correct Trinitarian formula. The matter came to the fore when a longstanding member of his congregation had been present for the administration of baptismal vows to new converts. Upon hearing the baptismal questions and the catechumens’ answers, he realized that he had neither been baptized with the same questions, nor had he affirmed the same faith. No longer sure he had been properly baptized, he begged to be baptized again (Eusebius, Church History, Book 7, 11.2-3). Dionysius did not know what to do, and wrote to Xystus, bishop of Rome, to ask for advice.

In his letter, Dionysius shows us not only the essence of the Dismissal, but also the prevailing order of the liturgy in which the “Amen” followed immediately after the Eucharist. As he expresses in his letter, he was not inclined to re-baptize a man who had for years been present for the Eucharist, had joined in the Apostolic “Amen,” and had participated in the Lord’s Supper:

But I did not dare to do this; and said that his long communion was sufficient for this. For I should not dare to renew from the beginning one who had heard the giving of thanks (εὐχαριστίας) and joined in repeating the Amen; who had stood by the table and had stretched forth his hands to receive the blessed food; and who had received it, and partaken for a long while of the body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ. But I exhorted him to be of good courage, and to approach the partaking of the saints with firm faith and good hope. (Eusebius, Church History, Book 7, 11.5-6; Migne, P.G. 20, 656)

There is nothing in Dionysius’ description, of course, to suggest that the Eucharist was anything other than a liturgical Eucharist offering of the tithes with prayer, just as his contemporaries celebrated, and the “Amen” anything other than the Apostolic “Amen” mentioned in 1 Corinthians 14:16 immediately following the Eucharist. The translator has the communicant standing at the table to receive “the blessed food,” giving the appearance that the blessing, or consecration, had taken place via the Eucharist, but the Greek merely says τῆς ἁγίας τροφῆς which means, “the holy food.” As we saw in the Didache (chapter 9), Irenæus (Against Heresies, Book IV, 18.5) Hippolytus (Anaphora 5-6), Tertullian (de Spectaculis 25), Firmilian (Epistle 74 to Cyprian, 9), and Cyprian (the Lapsed, 26), the food is “heavenly,” “holy,” and “sanctified” merely by being set aside as a tithe, and there is no cause for interpreting ἁγίας τροφῆς in any other way here with Dionysius. He clearly has the Eucharist distributed in its sanctified, but unconsecrated state. If Dionysius’ liturgy is similar to that of his Alexandrian predecessor, Origen, or his contemporary, Cornelius, it should not surprise us that the consecration would have occurred after the distribution, as suggested by his very words,

…who had stood by the table and had stretched forth his hands to receive the holy food; and who had received it, and partaken for a long while of the body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ.

The language is consistent with a consecration that occurs after the distribution as we saw with Cornelius, and as we saw with Origen in our previous post: “we also eat the bread presented to us; and this bread becomes by prayer a sacred body” (Origen, Against Celcus, Book VIII, 33). We have no indication from Dionysius on the nature of the Epiclesis, but whatever consecration Dionysius had in mind, it was clearly after the “Amen.” Dionysius’ description of the liturgy is therefore consistent with that of the first three centuries and, when viewed through the lens of that era, is wholly consistent with the contemporary liturgical order of a Eucharist, an “Amen,” and an Epiclesis.

Roman Catholic Migne concedes, at least, that the “Amen” mentioned by Dionysius is the same “Amen” mentioned by Justin Martyr in his First Apology (66), the very same “Amen” mentioned by Paul “in Epistola I ad Corinthios, cap. XIV.” But to contextualize it, and in fact to correct it, he defers to Florus the Deacon (9th century) who reports that “Amen” is actually the response of the faithful to the consecration (Migne, P.G. 20, 655n; c.f. Migne, P.L. 5, 97n). By this means, Migne has used a medieval liturgy as the lens through which the ancient liturgy is to be understood and interpreted. As we noted above, Migne believed Dionysius’ Eucharist to be consecratory, and used that assumption to understand Cornelius’ “offering” to be an oblation of consecrated bread, to which the people responded “Amen.” Through that series of invalid assumptions, Migne collapsed both Dionysius’ and Cornelius’ Eucharist into the Epiclesis to ensure that the ancient bishops of Alexandria and Rome are seen to be offering consecrated bread and wine in the Eucharist.

We will conclude this series in our next post as we analyze the rewriting of the liturgy of Gregory of Nazianzus, the Elder (c. 276 – 390 A.D.), as well as the liturgy of Athanasius of Alexandria (c. 298 – 373 A.D.), who retained the ancient, Apostolic liturgical order until his death late in the 4th century.

Follow

Follow

How much damage did Migne do? Incalculable. So encouraging to learn the truth. Thx k

Migne, in many cases, was reflecting what he had read and understood from his predecessors. The rewriting of the early liturgies spans centuries (centuries before and since Migne), as evidenced by John of Damascus (8th century) and his claim that the early writers only called the elements of the Supper “antetypes” before the consecration and Migne’s deference to Florus the Deacon (9th century). Migne often quotes those earlier writers and commentarians to support his position and conclusions.