With this post, we conclude our series on the creative but unconscionable rewriting of the early liturgies to make them conform to the late-4th century novelty in which Christ is said to be offered to the Father in the Eucharist. From the earliest days of the Church, the Eucharist was a sacrifice of thanks and praise to the Lord, a tithe offering. It was followed by an “Amen” (1 Corinthians 14:16) and then bread and wine from the thank offering were taken and consecrated for the Lord’s Supper. The moment of Consecration originated as a simple recitation of Christ’s words of institution: “This is My body, broken. … This is My blood, shed…”. It later came to be called “the Epiclesis,” literally, the Invocation, the liturgical moment when God—the Spirit, the Son or the Trinity—is asked to make the bread and wine into a spiritual meal for His people. And thus, a very simple liturgy prevailed for three hundred years: A Eucharist. An Amen. An Epiclesis. At the end of the 4th century, the order changed and the Epiclesis was moved before the Eucharist offering, which changed a simple tithe offering for the poor into a sacrifice of consecrated bread and wine. Thus was born the abominable Roman Catholic liturgical sacrifice of Christ’s body and blood. That discontinuity in the history of the liturgy puzzled and confounded scholars, historians, translators and apologists who could not explain why the early liturgy was so fundamentally different from the medieval one. Attempting to establish retroactive continuity, the academic community therefore engaged in a reprehensible campaign to edit, redact, mistranslate and subvert the early liturgies to “correct” the ancient writers and force them into conformity with the late 4th-century novelty. The effect of the historical revision has been to make the ancient Eucharist consecratory, essentially collapsing the ancient Eucharist into the Epiclesis, and thus creating the appearance that the ancient Eucharist offering of the early church was itself the Consecration.

Last time we reviewed the liturgies of Cornelius of Rome (250 A.D.), Cyprian of Carthage (253 A.D.), and Dionysius of Alexandria (256 A.D.). This time, we pick up with Gregory of Nazianzus, the Elder (c. 276 – 390 A.D.) and the liturgy of Athanasius of Alexandria (d. 373 A.D.). We find in Nazianzus evidence that the ancient Eucharist was simply the tithe offering for the poor and the stranger, as well as evidence tampering by the scholars in order to collapse his Eucharist into his Epiclesis. We find in Athanasius evidence that the ancient biblical liturgy had survived uncorrupted even to his day, while all around him the world was falling into novelty, abomination and apostasy. We conclude with a recap of the whole sordid history of redaction, editorializing, interpretive license, creative revision and freelance historiography by which the academic community has mishandled and refashioned the ancient liturgy.

Gregory Nazianzus the Elder (c. 276 – 374 A.D.)

Very little is known of Gregory Nazianzus the Elder (d. 374 A.D.) except from the Orations of his son, Gregory Nazianzen the Younger (d. 390 A.D.). Nevertheless, what we know of the Elder’s liturgy is consistent with the Apostolic liturgy of the early Church. To Gregory the Elder, “the Eucharist” was the tithe offering for the widow, the orphan, and the stranger. This is evident from Gregory the Younger’s eulogy of his father who was “sympathetic in mind, … bounteous in hand, towards the poor … relieving poverty as far as he could” (Nazianzen, Oration 18.20). Such was the Elder’s Eucharist offering that among all men, he was most prompt in his support for the poor, with a “readiness, which is a greater and more perfect thing than the mere offering” itself (Nazianzen, Oration 18.20). It is of no small interest to us that Gregory the Elder’s disposition toward the poor was “greater and more perfect” than “the mere offering,” which is not what we would expect if it was Christ’s body and blood that was being offered. Gregory’s “readiness,” of course, could not be “greater and more perfect” than Christ’s body and blood, nor could Christ’s body and blood ever be considered “the mere offering” in comparison to Gregory’s generosity. Clearly, the offering in view was the collection for the poor.

We may also discern the focus of Gregory the Elder’s Eucharistic liturgy by his wife’s participation in it, something the Younger also addressed in the same Oration. We recall from part 3 of this series, Tertullian chastised those who skipped the Eucharist—which was ostensibly an expression of joy and gladness—because they insisted on remaining solemn until the Supper. Additionally, Tertullian understood the Eucharist offering of the church to be “the ascription of glory, and blessing, and praise, and hymns” (Against Marcion, Book III, 22) and “simple prayer from a pure conscience” (Against Marcion, Book IV, 1), while he understood the consecration to occur after the Eucharist offering was complete, and indeed even after the bread had already been distributed for the meal (Against Marcion, Book IV, 40). Tertullian thus distinguished between the Eucharist and the Supper, the Eucharist itself occurring prior to the Consecration, and the Supper occurring after. When Tertullian chastised those who skipped “the sacrificial prayers,” his basis for the admonition was that “the Eucharist” does not “cancel a service devoted to God,” and thus they were wrong to skip “the sacrificial prayers.” Their “station” (fast) would “be more solemn,” he insisted, if they participated in both the Eucharist and the Supper (Tertullian, On Prayer 19). This is significant to us because the liturgy of Nazianzus followed the same sequence.

After the fashion of remaining reverently thankful during the thanksgiving offering, the Elder’s wife, Nonna, remained silent and respectful while he was conducting his eucharistic liturgy. She refrained from expressions of woe and grief, though “greatly moved even by the misfortunes of strangers,” unwilling as she was “to allow a sound of woe to burst forth before the Eucharist” (Nazianzen, Oration 18.10). It is of no small interest to us that during Gregory’s Eucharist offering his wife’s thoughts were occupied with the needs of the stranger rather than the sufferings of Christ, for to her, and for centuries before, the Eucharist was the tithe offering for the widow, the orphan and the stranger, not an offering of the body and blood of Christ. After all, as we read in the Didascalia, the purpose of “the Eucharist of the oblation” is so “that thou mayest share it with strangers for this is collected and brought to the bishop for the entertainment of all strangers” (Didascalia, 9). Small wonder that Nonna’s thoughts were occupied with the “the misfortunes of strangers” during the Eucharist. Relieving the condition of strangers was the very purpose of the Eucharist. We are thus left in no doubt what the Elder’s Eucharist was, and the purpose for which he offered it. It was the tithe offering for the poor. For the widow, the orphan and the stranger.

And thus, when Gregory the Younger recalls his father reciting “the customary words of thanksgiving (εὐχαριστίας)” over the offering (Nazianzen, Oration 18.29 Migne, P.G. 35, 1021) there is no doubt at all what manner of “customary words” of Eucharist they were. And yet, to reconcile Gregory’s early-4th century liturgy with the abominable late-4th century liturgy that succeeded it, the scholars have long since concluded that by his “customary words” of Eucharist, Gregory the Younger must have meant to refer to his father’s “customary words” of Epiclesis. That historical revision occurs in Oration 18.

- Oration 18

Gregory the Younger recalls an occasion when Gregory the Elder was in poor health when the time came to offer the Eucharist. “The time of the mystery had come, and the reverend station and order, when silence is kept for the solemn rites” (Nazianzen, Oration 18.29), the same silence observed by his wife “before the Eucharist.” Though seriously ill, Gregory the Elder nevertheless managed to rise from his bed and gather just enough—only enough—energy to offer those sacrificial prayers of thanksgiving. “Then, after adding the customary words of thanksgiving (εὐχαριστίας, eucharistias),” the Elder returned to his bed, enjoyed some rest and refreshment, and then returned the next day, and “with the full complement of clergy, … offered the sacrifice of thanksgiving (θύει τὰ χαριστήρια).” (Nazianzen, Oration 18.29; Migne, P.G. 35, 1021).

There is no shortage of “customary words of thanksgiving” in the ancient record. Justin Martyr (c. 150 A.D.) describes “prayer and thanksgiving for all things wherewith we are supplied” (First Apology, 13). Irenæus (189 A.D.) insists that “in all things” we must “be found grateful to God our Maker … offering the first-fruits of His own created things” (Against Heresies, Book IV, Chapter 18, 4). His disciple, Hippolytus (215 A.D.), instructs the newly ordained bishop to pray, saying “We give thanks to you, God, and offer to you the firstfruits of the fruits which you have given to us as food, having nourished them by your word, commanding the earth to bring forth all kinds of fruit … adorning all creation for us with various fruits” (Anaphora, 32). Hippolytus’ thanksgiving oblation was performed with “the whole council of elders,” or in Gregory’s language, “with the full complement of clergy,” and quite notably is performed before the Holy Spirit is invoked for the meal:

“Then the deacons shall present the oblation to him, and he shall lay his hand upon it, and give thanks, with the entire council of elders…” (Hippolytus, Anaphora, 4)

We know what the Eucharist is, and we know what it means to give thanks for “all kinds of fruit.” The “customary words of thanksgiving” described for us in Gregory’s Oration 18 clearly refer to the Eucharist. The thank offering. The tithe for the poor. Prior to the Consecration.

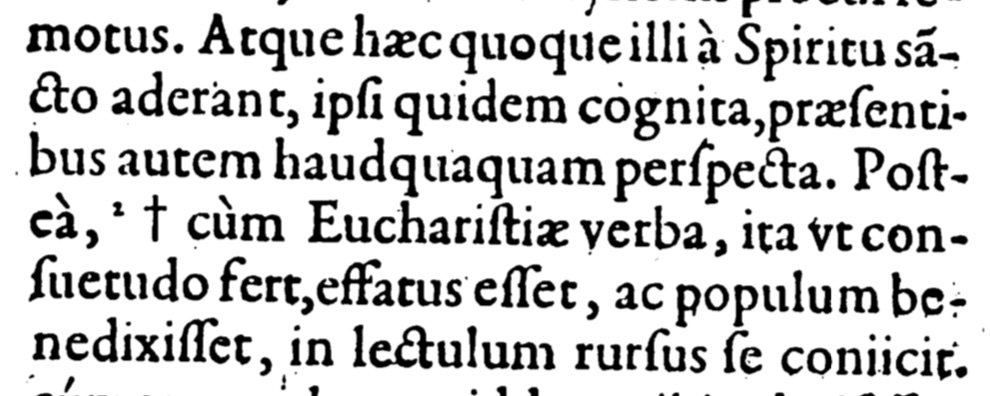

This of course is inconsistent with the medieval liturgy, and therefore Gregory must be edited and corrected to make the Elder’s liturgy conform to the later novelty. The subtle revision of history occurs at Gregory’s recollection of his father’s “customary words of thanksgiving.” Roman Catholic Jaques de Billy (1609) with a gratuitous editorial mark (†) in the Latin rendering intends to ensure that “Eucharistiæ verba,” or “customary words of thanksgiving,” are interpreted as the Consecration:

Roman Catholic Jacque Migne, repeated the error nearly 250 years later, deferring to de Billy to indicate that the Greek—τῆς εὐχαριστίας ῤήματα, “the customary words of thanksgiving”—must have been a reference to the Consecration, or possibly to the Dismissal after the Supper:

Billius: … Verum in notis observat, per “eucharistiæ verba”, vel ea intelligi posse, quibus consecratio perficitur; vel ea, quibus sub Missae finem a sacerdote, ob sacrosanctum epulum, “Deo gratiae agebantur.” (Migne P.G. 35, 1021, n29)

Billy: … Verily by his marks observed, “the words of thanksgiving”, can either be understood to mean that the consecration was completed; or that the priest concluded the Mass and the sacred banquet with “Thanks be to God.”

By this means—with editorial marks and academic presumption—the plain meaning of Nazianzus’ “customary words of thanksgiving” was subverted and reinterpreted to ensure that it conformed to the later medieval novelty. De Billy’s editorial mark (1603) and Migne’s conjecture (1857) were nothing more than wishful attempts to redact Nazianzus’ early liturgy and collapse his Eucharist into the Epiclesis to give the impression that the Elder had offered consecrated bread and wine as his Eucharist.

Athanasius of Alexandria (296 – 373 A.D.)

We conclude this series with Athanasius, not because his liturgy has been retroactively corrupted or altered, but rather because within his writings we find the last vestiges of liturgical orthodoxy before the whole world fell into error and apostasy. Athanasius provides late-4th century evidence of a Eucharist, an Apostolic “Amen,” and an Epiclesis in the Biblical order, a liturgy that actually can be traced to the apostles. The scattered references in his works confirm to us that the apostolic liturgy had indeed survived in its Biblical form for three hundred years until the late 4th century. The evidence for his Biblical liturgy is found in his Festal Letters and in his Sermon to the Newly Baptized.

- Festal Letter 45 (373 A.D.)

That Athanasius understood the sacrifice of the church to be the offering for the poor is understood from his 45th Festal Letter. “Let us all take up our sacrifices, observing distribution to the poor,” he exhorted, “and enter into the holy place, as it is written…” (Festal Letter 45). It was his annual tradition of sending out a letter to celebrate the Passover of Christ. The Passover sacrifices were for “distribution to the poor,” consistent with the Didascalia, which states explicitly that “the Eucharist of the oblation” is to be “brought to the bishop for the entertainment of all strangers” (Didascalia, 9).

- Festal Letter 11 (339 A.D.)

Athanasius understood those Passover sacrifices for “distribution to the poor” as his Eucharist offering, since he invoked Paul’s use of εὐχαριστεῖτε, thanksgiving, in 1 Thessalonians 5 to describe them:

For what else is the feast, but the constant worship of God, and the recognition of godliness, and unceasing prayers from the whole heart with agreement? So Paul wishing us to be ever in this disposition, commands, saying, “Rejoice evermore; pray without ceasing; in everything give thanks (εὐχαριστεῖτε, eucharisteite).” (1 Thessalonians. 5:16-18). (Festal Letter 11.11)

Athanasius continues in the same letter, instructing Christians that their sacrificial offerings are the fulfillment of Malachi 1:11, saying,

And the sacrifice is not offered in one place, but “in every nation, incense and a pure sacrifice is offered unto God.” (Malachi 1:11) (Festal Letter 11.11)

Athanasius concludes with the Pauline “Amen” (1 Corinthians 14:16), his Eucharist offering resonating with Justin’s (First Apology 65, 67), Irenæus’ (Against Heresies, Book I, 14.1), Hippolytus’ (Refutation of All Heresies, Book 6, chapter 37) and Dionysius’ (Eusebius, Church History, Book 7, 11.5-6) “Amen” that all say in unison immediately following the Eucharist offering:

So when in like manner from all in every place, praise and prayer shall ascend to the gracious and good Father, when the whole Catholic Church which is in every place, with gladness and rejoicing, celebrates together the same worship to God, when all men in common send up a song of praise and say, Amen; (Festal Letter 11.11)

- Sermon to the Newly Baptized (373 A.D.)

Athanasius’ Epiclesis was an appeal to the Logos to come down into the bread and wine that they may become a meal for His people:

You shall see the Levites bringing loaves and a cup of wine, and placing them on the table. So long as the prayers of supplication and entreaties have not been made, there is only bread and wine. But after the great and wonderful prayers have been completed, then the bread is become the Body, and the wine the Blood, of our Lord Jesus Christ. ‘And again:’ Let us approach the celebration of the mysteries. This bread and this wine, so long as the prayers and supplications have not taken place, remain simply what they are. But after the great prayers and holy supplications have been sent forth, the Word comes down into the bread and wine – and thus His Body is confected. (Athanasius, Sermon to the Newly Baptized)

His reference to the “loaves” brought by the Levites is a reference to the thank offering of the first fruits, as indicated in Leviticus 23:

Ye shall bring out of your habitations two wave loaves of two tenth deals: they shall be of fine flour; they shall be baken with leaven; they are the firstfruits unto the LORD (Leviticus 23:17)

Athanasius thus indicates that until the bread and wine are consecrated, they are but a first fruit offering, as also suggested in Festal Letter 45, “Let us all take up our sacrifices, observing distribution to the poor, and enter into the holy place.” After the consecration they are the body and blood of Christ. It is notable that when Athanasius describes the Eucharist prayers, they are just gladness, rejoicing, praise, prayer, worship and thanksgiving. But when he describes the consecratory prayers, they are “great,” and “wonderful” and “holy” prayers and supplications—a different order of prayer entirely. Additionally, when Athanasius refers to sacrifices that are offered to the Lord (Festal Letters 11 and 45), he mentions first-fruit offerings, distribution to the poor and thanksgiving to God but makes no mention of Christ’s body and blood. But when he mentions the Epiclesis and the meal (Sermon to the Newly Baptized), he mentions the body and blood of Christ, but makes no mention of offering or sacrifice.

Athanasius’ liturgical sacrifice may therefore be summarized as a tithe offering for the poor, accompanied by praise and prayer, gladness and rejoicing in Eucharistic gratitude for the Lord’s provisions. The Eucharist was followed by the Apostolic “Amen” (1 Corinthians 14:16), indicating that the Eucharist offering was over. Then in preparation for the meal, with the “great and wonderful prayers” of the Epiclesis and by the “great prayers and holy supplications,” a request is made that the bread and wine may become a meal of Christ’s body and blood to His people. His liturgy was Biblical and Apostolic: A Eucharist. An “Amen”. An Epiclesis. That was the liturgical order of the early church and it prevailed as the mark of orthodoxy all the way through the death of Athanasius.

The Late 4th Century Change

But changes were afoot throughout the latter part of the 4th century, and the apostolic liturgy began to be reordered. As we noted at the beginning of this series, the Consecration migrated to a liturgical position prior to the offering, and instead of a tithe offering of gratitude and the first-fruits of the harvest, the Eucharistic oblation became a propitiatory offering of the body and blood of Christ. Cyril of Jerusalem (c. 350 A.D.) considered the Eucharist to be a “sacrifice of propitiation” in which we “offer up Christ sacrificed for our sins,” to remit the penalties of sin for both the living and the dead (Catechetical Lecture 23 8-10). Serapion of Thmuis (c. 353 A.D.) offered the oblation prior to the Epiclesis, but nevertheless believed it to be a propitiatory offering of “the likeness of the holy Body” and “a likeness of the Blood” of Christ, that the Lord would “through this sacrifice be reconciled to all of us and be merciful” (Sacramentary, Paragraph B). The Apostolic Constitutions (375 A.D.) instructed the bishop to ask the Lord to “send down upon this sacrifice Your Holy Spirit” (VIII 12) to make it Christ’s body and blood “that the good God will accept it … upon His heavenly altar” (VIII 13). At the same time, first-fruit thank offerings such as “honey, milk” and “any necessaries” were no longer to be offered on the altar but sent directly to the bishop for redistribution. The only allowed offerings being bread and wine as “our Lord has ordained,” “excepting grains of new grain, or ears of wheat, or bunches of grapes in their season” (Apostolic Constitutions, XLVII.3-4), a change that greatly reduced the content of the “eucharist offering,” effectively reducing it to consecrated bread and wine. By 382 A.D., Gregory of Nyssa proposed that Jesus had really sacrificed Himself for our sins the night before He died, instituting an offering of consecrated bread and wine: “He offered himself for us, Victim and Sacrifice … [w]hen He made His own Body food and His own Blood drink for His disciples” (On the Space of Three Days I). Gregory of Nazianzen (383 A.D.) asked his friend to loose him from his sins by “the Sacrifice of Resurrection … when you draw down the Word by your word [the Epiclesis], when with a bloodless cutting you sever the Body and Blood of the Lord, using your voice for the glaive [sword]” (Epistle 171, to Bishop Amphilochius of Iconium). John Chrysostom (387 A.D.), describing the Supper, said we “see the Lord sacrificed, and laid upon the altar, and the priest standing and praying over the victim, and all the worshippers empurpled with that precious blood” (Treatise on the Priesthood III.4). Ambrose of Milan (389 A.D.), insisted, though Christ be not seen, “nevertheless it is He himself that is offered in sacrifice here on Earth when the body of Christ is offered” (Psalms, Psalm 38, paragraph 25). Macarius the Elder (d. 390 AD), though retaining the symbolic nature of the bread and wine, insisted “in the church bread and wine should be offered, the symbol of His flesh and blood” (Homilies 27.17). Early in the 5th century, Augustine (408 A.D.) had fallen for the lie as well: “… is He not likewise offered up in the sacrament as a sacrifice … daily among our congregations; so that the man who, being questioned, answers that He is offered as a sacrifice in that ordinance, declares what is strictly true?” (Letters 98.9). But it was all nonsense, a gross departure from the Biblical liturgy that had prevailed for the preceding centuries. The apostasy of Paul’s inspired foresight (2 Thessalonians 2:3) had arrived.

Since then, the late-4th century liturgical novelty of a sacrifice of Christ’s body and blood in the Lord’s Supper—whether symbolically, or really—has largely been taken as evidence of a longstanding, ancient Apostolic liturgical offering of consecrated bread and wine, despite the fact that the early liturgies knew nothing of it. To reconcile the glaring historical discontinuity, the rewriting of history began, and the ecclesiastical scholars and historians repeatedly tampered with the evidence to force the writers of the first three centuries to conform to the novelties of the late-4th and beyond. That rewriting of history was done by the most novel, creative and deceptive means imaginable.

The Collapse of the Eucharist

The migration of the Epiclesis from after the Amen to before the Eucharist is easily and abundantly documented. We have no evidence of a propitiatory offering of the Lord’s Supper until the 350s A.D., and the offering of Christ’s alleged body and blood as the sacrifice of Christ’s Church does not appear any sooner. Prior to the late-4th century, Malachi 1:11 was understood to be the Church’s offering of the tithes for the widow, the orphan and the stranger. Afterward it was taken to refer to the liturgical offering of Christ’s body and blood. The striking contrast between a liturgical tithe offering prior to the Epiclesis and the abominable offering of the body and blood of Christ after the Epiclesis is well known, and many a historian has struggled to reconcile them. The point of this series has been to showcase the innovative, creative and occasionally ridiculous means by which the scholars, apologists, liturgists and translators have redacted and modified the ancient evidence to force it to fit with the later novelty. Their efforts resulted in a wholesale and unconscionable reinterpretation of the ancient Eucharist offering as if it was the ancient Epiclesis. In a word, the experts from academia collapsed the ancient Eucharist into the ancient Epiclesis in one of the most embarrassing blemishes on the history of their craft. The evidence is damning.

To conclude the series, we provide a digested compendium of the sordid history of evidence tampering and editorial license by the academic community. The reader is invited to consider as he reviews what follows that the unrestrained redaction documented below reveals the current and shameful state of historical liturgiology in academia:

- The Didache (mid-1st century)

The Didache is replete with sacrificial Eucharistic language, complete with an “Amen” to conclude the offering. But lacking an Epiclesis, the Roman Catholic has imagined one in order to make sure the Eucharist offering of the Didache was consecrated before it was offered. The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Bible and Theology acknowledges that there is no epiclesis in the Didache, but presumes that the Eucharistic prayer must have served that role:

“The Didache has no epiclesis, just as it lacks an institution narrative. It has been suggested that the invocation of the divine name constitutes an epiclesis (10:22). Odo Casel [1934] popularized the view that the whole eucharistic prayer is consecratory, and that the formal epiclesis within the prayer plays a complementary role by indicating the purpose of the invocation.” (Encyclopedic Dictionary of Bible and Theology, Epiclesis)

The Roman Catholic Encyclopedia likewise simply assumes, without evidence, that the Eucharistic prayers of the Didache must have occurred prior to the Eucharist: “These are clearly prayers after the Consecration and before Communion. …though there is no distinct mention of the Real Presence” (Roman Catholic Encyclopedia, the Didache). By this means, the ancient Eucharist is collapsed into the Epiclesis to ensure that the Eucharist offerings consisted of consecrated bread and wine.

- Clement of Rome (mid-late 1st century)

In his letter, Bishop Clement instructed the rich to “provide for the wants of the poor” and the poor to “bless God” for the rich “by whom his need may be supplied” for “we ought for everything to give Him thanks (ευχαριστειν)” (Clement, to the Corinthians 38; Migne P.G., vol I, 285). In the same letter, Clement also defended the presbyters who had been faithful in their handling of the gifts, or as Clement writes, “τὰ δῶρα” (Migne P.G., vol I, 300). It is the same word used in the Gospel of Luke to refer to the tithes being deposited into the temple treasury (Luke 21:1). Clearly, Clement had been referring to the presbyters’ faithful handling of the tithes for the poor. The gifts. Yet all the major translations of Clement studiously avoid calling them “gifts” and instead say the presbyters of the church faithfully “offered up sacrifices” (The Apostolic Fathers, vol 1, Gerald G. Walsh, S.J (1947)), “offered its sacrifices” (The Apostolic Fathers, vol 1, Kirsopp Lake (1919)), “fulfilled [their] duties” or “presented the offerings” (Schaff’s Ante-Nicæne Fathers (1885)). This remarkable stubbornness gives cover to the Roman Catholic who then uses these translations to prove that the early church offered a sacrifice of Christ’s body and blood. It is subtle, but the studious aversion to translating “τὰ δῶρα” as “the gifts” collapses the ancient Eucharist into the Epiclesis to ensure that the ancient sacrifices appear to consist of consecrated bread and wine.

- Ignatius of Antioch (107 A.D.)

Ignatius is assumed to have affirmed transubstantiation, and therefore the “real presence” of Christ in the Eucharist, and therefore the offering of Christ’s body and blood in the Supper, in his letter to the Smyrnæans:

“They abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer, because they confess not the Eucharist to be the flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ, which suffered for our sins, and which the Father, of His goodness, raised up again.” (Ignatius, to the Smyrnæans, 7)

However, Ignatius made this comment in the context of the Eucharistic tithe offering for the widow, the orphan and the stranger, as is plainly evident from the letter. This may be seen when one includes the immediately preceding sentence:

They have no regard for love; no care for the widow, or the orphan, or the oppressed; of the bond, or of the free; of the hungry, or of the thirsty. Let us stand aloof from such heretics. They abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer, because they confess not the Eucharist to be the flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ… (Ignatius, to the Smyrnæans, 6-7)

As we showed in part 1 of this series, the early liturgical practice was to dismiss the catechumens, the backslidden and unbelievers before the Eucharistic tithe offering with prayers of gratitude. Ignatius’ first reference—”the Eucharist and … prayer”—refers to that. Heretics would have been dismissed from the service before the Eucharist and prayer were offered. Bread from the Eucharistic offering was then distributed and consecrated for the meal. In Ignatius’ day, the Consecration was simply a recitation of Christ’s own words—”This is My body, broken…”—pronounced over bread that had been taken from the Eucharist to be used for the Supper. Thus, his second reference—”they confess not the Eucharist to be the flesh” of Christ that suffered—is simply a reference the heretics’ unwillingness to recite the Consecration that was spoken over the bread from the tithe offering. The heretics he has in mind, of course, are the gnostics who denied that Jesus came in the flesh, suffered, died and arose.

Ignatius’ statements are thus easily contextualized. The heretics abstained from “Eucharist and from prayer” (the tithe offering) because they have no care for the widow, the orphan and the stranger and, being gnostic, were unwilling to recite the words of Consecration—”This is My body, broken…”—over the bread taken from the Eucharist to be used for the Supper. Without that context, the academic community has simply collapsed Ignatius Eucharist offering into the Consecration, obscuring the fact that “they confess not the Eucharist to be the flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ” simply means that the heretics are unwilling to pronounce the words of Consecration over the bread taken from the tithe offering.

Justin Martyr (c. 150 A.D.)

In Chapter 13 of his First Apology, Justin describes the Eucharist that is gratefully offered with “thanks by processions of speech (διά λόγου πομπάς) and sending forth hymns for our creation,” in an obvious reference to the tithe. But because διά λόγου πομπάς was difficult to translate, the scholars chose to render it as “invocations,” leaving the impression that the Eucharist was offered by Consecrating it.

In Chapter 65 of his First Apology, Justin explains that the bread and wine are “eucharisted,” which is to say that “thanksgiving was pronounced” over them, followed immediately by the Apostolic “Amen” (First Apology, 65). Then in the next chapter he explains that the Consecration is spoken over “Eucharisted food” (εὐχαριστηθείσαν τροφήν) (First Apology, 66), showing definitively that the Consecration followed rather than preceded the Eucharist. To cover up that fact, translators have simply turned his statement, “by the prayer of His word eucharisted food … is both the flesh and the blood of that incarnated Jesus,” into “the food which has been made into the Eucharist by the Eucharistic prayer set down by Him … is both the flesh and the blood of that incarnated Jesus” (Jurgens, The Faith of the Early Fathers, vol 1 (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press (1970) 55). That gives the appearance that the Eucharist was itself the Consecration.

In both cases, the translators have represented Justin’s Eucharist as if it was his Epiclesis, giving the impression that he believed the church offered consecrated bread and wine in the Eucharist.

Irenæus of Lyons (c. 189 A.D.)

When Irenæus complained that the heretic, Marcus, was imitating the Christian liturgy, he distinctly wrote that Marcus would pretend “to eucharist (εὐχαριστείν) cups mixed with wine, and protracting to great length the word of epiclesis (ὲπικλήσεως)…”. To conceal the fact that the Eucharist liturgically preceded the Epiclesis, the translators changed the wording to say that Marcus would pretend “to consecrate cups mixed with wine, and protracting to great length the word of invocation (Against Heresies, Book I, Chapter 13, paragraph 2).” That gives the impression that the Eucharist was itself the Epiclesis.

When Irenæus explained that the bread of the harvest becomes the Eucharistic tithe offering when it receives “the summons (έκκλησιν) of God” as in Malachi 3:10 (Against Heresies, Book IV, 18.5) translators could not understand that he was referring to the Lord summoning the tithe to the storehouse. So they simply switched out the word (έκκλησιν, ecclisin), and substituted (επικλυσιν, epiclisin), noting that “epiclisin” was the “preferred” rendering (Migne, PG, VII, 1028n). The passage was thus made to say that the bread of the harvest becomes the Eucharist when it receives “the invocation (επικλυσιν, ) of God,” giving the impression that the bread did not become the Eucharist until it was consecrated.

When Irenæus explained in his native Greek that at the moment of Consecration, “… the Eucharist becomes the body of Christ” (Schaff, Phillip, Ante-Nicæan Fathers, vol I, note 4462), it proved that he believed the bread was already the Eucharist before it was consecrated, as also evidenced by (Against Heresies, Book I, 13.2 and Book IV, 18.5, above). To obscure that fact, translators deferred to the corrupted Latin, and instead rendered the passage, “When, therefore, the mingled cup and the manufactured bread receives the Word of God, … the Eucharist of the blood and the body of Christ is made… (Against Heresies, Book V, chapter 2, paragraph 3). That gives the false impression that the bread and wine became the Eucharist at the Epiclesis.

When Irenæus explained that “the oblation of the Eucharist” precedes the Epiclesis by which “we invoke the Holy Spirit” (Irenæus, Fragment 37), scholars quickly pounced on the evidence and attempted to discredit Pfaff, who discovered the fragment, and criticized it for being “too Lutheran.”

In all these cases, the scholars attempted to collapse Irenæus’ Eucharist into his Epiclesis to give the impression that he believed the bread and wine became the Eucharist at the Consecration, and that the Eucharist was an offering of Consecrated bread and wine. When evidence was found to overturn that assumption, the scholars attempted to delegitimize the evidence.

Hippolytus of Rome (215 A.D.)

When Hippolytus insisted in his Anaphora that newly baptized Christians should bring their own Eucharist of cheese, olives, oil, wine and bread with them to church on the day they were baptized, the scholars could not understand why Hippolytus included olives, cheese and oil in the Eucharist. One scholar thus swore “to use a heavy black marker to ‘x’ out ruthlessly all references to Hippolytus in text books of liturgical history” (The So-Called Apostolic Tradition of St. Hippolytus of Rome, 2015), and another assumed that Hippolytus had simply exuded an exaggerated reverence for a “primitive custom” of a bygone era (The Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus, Easton, Burton Scott, trans (Cambridge University Press, 1934) 74). Neither could grasp that Hippolytus understood the Eucharist to refer to the tithe offering, and both were dismissive of what Hippolytus was plainly saying.

Additionally, Roman Catholic Easton, in an attempt to normalize Hippolytus to make him conform to the later liturgies, assumed 1) that by “The bishop shall give thanks (gratias agat) for the bread” (Anaphora, 21; Hauler, 112), Hippolytus must really have meant to consecrate the bread (Easton, 48), and 2) by “Having blessed (benedicens) the cup” to consecrate it (Hauler, 117), Hippolytus must have meant to give thanks for it (Easton, 60). Thus, the scholars were either dismissive of what Hippolytus had plainly written, or attempted to correct him to give the appearance that Hippolytus’ Eucharist and his Consecration were interchangeable.

In his Second Fragment on Proverbs 9, Hippolytus wrote that the “honoured and undefiled body and blood” of Christ are present on the “the mystical and divine table … every day that the sacrifices are offered.” It is a matter of simple inspection of his other writings to show that the bread and wine are on the table each time the sacrifices are offered, for the simple reason that the Consecration always followed the Eucharist offerings, and the Supper always followed the consecration. In a gratuitous translation of “απερ” as “which” instead of “as,” the meaning of his text is altered to suggest that, “His honoured and undefiled body and blood, … day by day are administered and offered sacrificially at the spiritual divine table.” This gives the impression that Hippolytus’ Eucharist offering followed the Epiclesis even though his known writings show that he believed, like Irenæus, that the Eucharist offering preceded the Consecration (Hippolytus, Refutation of All Heresies, Book 6, chapter 34).

In all these cases, the scholars attempted to collapse Hippolytus’ Eucharist into his Epiclesis to give the impression that he offered bread and wine by Consecrating it.

Tertullian of Carthage (208 A.D.)

Tertullian identified the Eucharist as “sacrificial prayers” distinct and separate from, and prior to, the Supper (On Prayer 19). He believed the sacrifices prophesied by Malachi were fulfilled in praise, prayer, hymns and “a gift” with thanksgiving (Against Marcion, III 22; IV, 1 & 9). He believed the Consecration occurred by saying “This is My body” after the distribution of the elements (Against Marcion, IV, 40). Because he saw the Eucharist as the “sacrificial offering” of “a gift” prior to the Supper, and the Consecration taking place after the distribution of the elements, it is clear that his reference to “the holy thing” (“sanctum protuleris”) over which the Apostolic “Amen” is spoken (De Spectaculis (The Shows) 25) was a reference to the Eucharistic tithe offering. Nevertheless, Roman Catholic Migne ignored the Biblical and other ancient evidence supporting an “Amen” spoken immediately after the Eucharist, and relied instead on late-4th century Ambrose and 5th century Augustine to assert that Tertullian’s “Amen” must have been spoken after the Consecration (Migne, P.L. vol I, col 658 (d)). And Anglican Sydney Thelwall, simply assumed “sanctum protuleris” was a reference to the consecrated elements, rendering it in English as “the Holy Thing” with capital letters, to give the appearance that Tertullian had intended to refer to an offering of the body and blood of Christ.

In both cases, the scholars essentially collapsed Tertullian’s Eucharist into his Epiclesis to give the impression that the holy thing was an offering of Consecrated bread and wine.

Origen of Alexandria (248 A.D.)

To Origen, the incense of the church is offered on “the altar” of the heart in the form of prayer (Against Celcus, Book VIII, 17), and the sacrifice of the church is “first-fruits [and] our prayers” (Against Celcus, Book VIII, 34). To him, the offering was “a symbol of gratitude (εὐχαριστίας) to God in the bread which we call the Eucharist (εὐχαριστία)” (Against Celcus, Book VIII, 56 (Migne, P.G. vol XI, col 1604)). He also understood the Consecration to occur by the invocation (έπικέκληται) of the Trinitarian name of God over the elements (Fragment 34 (Robertson & Plummer (135)). His Eucharist was plainly distinct from his Epiclesis. Yet the scholars, unable to reconcile his biblical liturgy with the later medieval one, have assumed that Origen “probably” included the Epiclesis in his Eucharist. Maurice De La Taille, S.J., in his Mystery of Faith: wrote, “even if Origen never affirmed it, that is no reason for saying that he denied that thanksgiving is contained in the consecrative prayer.” Edward J. Kilmartin, S.J., of Weston College School of Theology, simply assumed that by “invocation” Origen “probably refers to the [Eucharistic] prayer as a whole.” (Theological Studies, “Sacrificium Laudis: Content and Function of Early Eucharistic Prayers,” Volume: 35 issue: 2, page(s): 268-287 (May 1, 1974), emphasis added).

In both cases, unable to find in Origen an Epiclesis prior to the Eucharist, the scholars assumed that the Consecration was “probably” included in the Eucharistic prayer, and that the Eucharistic prayer was likely “consecratory.”

Firmilian of Cæsarea (256 A.D.)

From 254 to 258 A.D., a controversy arose between Stephen, Bishop of Rome, and three bishops from Asia and Africa, because Stephen had taught that the baptism of heretics was valid (Cyprian of Carthage, Epistle 73, paragraph 2). Among his detractors was Firmilian of Cæsarea who objected on the grounds that even if the Trinitarian baptismal invocation used the right words, the heretics did not believe in the same Father, Son and Spirit, and therefore the accompanying baptismal profession was invalid. His explicit and repeated concern was that the baptismal invocation and the baptismal profession had to be consistent before someone could be considered Christian and participate in the Eucharist or administer it. He illustrated his concern with a recent example to illustrate the absurdity of Stephen’s position: a female heretic who had offered the Eucharist after receiving a valid baptismal invocation, but without a valid baptismal profession (To Cyprian, from Firmilian, Epistle 74, paragraph 9; see the unredacted original Latin here). The academic community has ignored the fact that he was referring to the baptismal invocation of the Trinity, and interpreted Firmilian as if he had instead been complaining about the woman offering the Eucharist with a valid Consecration, giving the appearance that Firmilian believed the Eucharist was an offering of Consecrated elements. Because that erroneous assumption then created an internal inconsistency within Firmilian’s letter, the scholars then “agreed” among themselves that it was necessary to add an editorial “non” to his original letter to correct the inconsistency created by their assumption: “The word non is not in the manuscripts, but it seems to be generally agreed that the sense of the passage as a whole requires its insertion” (The Journal of Theological Studies, October 1954, New Series, Vol. 5, No. 2 (October 1954), pp. 215-220, emphasis added. (See the redacted Latin here).)

In this way, the scholars collapsed Firmilian’s Eucharist into his Epiclesis to give the impression that he believed the proper sacrifice of the Church was an offering of Christ’s body and blood.

Cornelius of Rome (250 A.D.)

Novatus had created a schism in Rome, and was using the Eucharistic liturgy to compel communicants to affirm their allegiance to him. In his complaint, Cornelius observed that Novatus had corrupted the substance of the liturgy, particularly the “Amen” after the offerings, and the Consecration for the meal after the Amen. His liturgical chronology reflects the biblical order: the offerings, the “Amen,” the Consecration, and the Supper, in that order (Eusebius, Church History, Book 6, 43.18-19). At no point did Cornelius complain that Novatus had corrupted the order of the liturgy. Novatus had only corrupted the “Amen” and the Consecration, not the order in which they were spoken. Unable to reconcile an “Amen” prior to the Consecration, Migne assumed that Novatus had also corrupted the order of the liturgy, and so added further explanations indicating that, of course, in a valid liturgy, the “Amen” would have followed the Consecration. To support his claim, he provided evidence from the late-4th and early-5th centuries in which the “Amen” followed the Consecration: Ambrose of Milan (On the Mysteries 54 (389 A.D.)), Cyril of Jerusalem (Catechetical Lectures 23 21 (350 A.D.)) and Augustine of Hippo (Contra Faustum, XII.10 (405 A.D.)) (Migne, P.G. 20, 628 (n53)).

By this means, Migne gives the impression that Cornelius’ normal liturgy would have included an offering after the Consecration rather than before it, essentially collapsing Cornelius’ Eucharist into his Epiclesis.

Cyprian of Carthage (253 A.D.)

Cyprian understood Malachi 1:11 to refer to the Eucharist offerings of the Church for the widow, the orphan and the poor, and included oil in those Eucharist offerings (Cyprian of Carthage, Epistle 69, 2). He expounded in great detail on upon the sacrifice of the Church, and even said “peace and brotherly agreement is the greater sacrifice to God” (Treatise IV On the Lord’s Prayer 23), which is hardly what one would say if he believed the Church offered Christ’s body and blood as the sacrifice to the Father. Our “peace and brotherly agreement,” no matter how laudable, could hardly be considered “greater” than Christ’s own body and blood. What is more, for all of his eloquent exegesis on Malachi 1:11, he omitted any reference to consecrated bread and wine as the sacrifice that fulfills it (Cyprian of Carthage, Treatise XII, Testimonies Against the Jews, Book I, chapter 16). Cyprian believed the liturgical offering of the church must be what “Christ Himself … offered” (Epistle 62, 14), and yet he denied that Jesus could have offered His own blood before He “had first been trampled upon and pressed” (Epistle 62, 17), showing that he did not believe Jesus had offered His own blood the night before He died.

It is true that Cyprian also wrote that “the Lord’s passion is the sacrifice which we offer,” which has been taken universally (against all the countervailing evidence) to mean that Cyprian believed the sacrifice of the Church was to offer Christ’s sufferings to the Father (Epistle 62, 17). The scholars arrive at that conclusion without knowledge or awareness that Cyprian used the word “offer” to mean “remembrance” and “commemoration,” something he demonstrates for us repeatedly throughout his works (see Epistle 33, 3; Epistle 36, 2; Epistle 57, 4; Epistle 59, 4; Epistle 65, 2).

Having ignored Cyprian’s repeated use of “offer” to mean “commemorate” and “remember,” the scholars also ignore his plain use of “sanctify” to refer to something being set aside for holy uses. The evidence for that constant use of the term, and the scholars’ acknowledgement of it, is found in Epistle 69, 2; Reinharti, 189; Treatise II, “On the Dress of Virgins,” 23; Migne, P.L. 4, 463; Treatise IV, “On the Lord’s Prayer,” 2; Migne PL 4.521; Treatise IV, “On the Lord’s Prayer,” 12; Migne PL 4.527; Treatise VIII, “On Work and Alms,” 2; Migne PL 4.603; Treatise VIII, “On Work and Alms,” 26; Migne PL 4.621; (Treatise XI “Exhortation to Martyrdom,” 3; Migne PL 4.653). Nevertheless, against all evidence, when Cyprian says it is imperative that “the Lord’s sacrifice [be] celebrated with a legitimate sanctification (sanctificatione)” (Epistle 62, 9; (Migne P.L. 4, col 381)), clearly referring to the Eucharistic prayer, the translators gratuitously render it, “the Lord’s sacrifice [be] celebrated with a legitimate consecration” (Epistle 62, 9), giving the impression that Cyprian believed the Church was obligated to offer consecrated bread and wine in the Eucharist.

It is known that the Eucharistic tithe offering was considered holy, and it is known from the Eucharistic Anaphora of Hippolytus that new catechumens were instructed “not to bring any vessel” except “that which each brings for the eucharist” and that it is important “that each bring the oblation in the same hour” (Anaphora 20). That practice is seen in Cyprian’s three examples of Lapsed Christians who “crept in among us when we were sacrificing” in his Treatise III “On the Lapsed” (paragraphs 25-26). In each case he details the offense of the Lapsed who came for the Sacrifices and then remained for the Supper. In the third example he speaks of a woman who “tried with unworthy hands to open her box, in which was the holy of the Lord (Domini sanctum),” a plain reference to the Eucharistic offering, and then continued by saying that a man present at the sacrifices “could not eat nor handle the holy of the Lord (sanctum Domini)” after the sacrifices, a plain reference to the consecrated elements of the Supper. Neither reference identifies what “the holy of the Lord” was, but contextually, and based on the preceding two examples, the first “holy of the Lord” refers to the tithe offering and the second refers to the consecrated meal. Setting aside the clear pattern established by Cyprian in the treatise, the translators assumed that the first reference to the woman who carried the Domini sanctum in her box must have been a reference to the consecrated elements, and so inserted “body” in the English translation: “And another woman, when she tried with unworthy hands to open her box, in which was the holy (body) of the Lord, was deterred by fire rising from it from daring to touch it.” This gives the impression that the woman had brought consecrated bread and wine with her to Church in order to offer Christ’s body to the Lord in the sacrifices.

In all these examples, the translators ignore the context and interpret Cyprian as if he believed the Church offers Christ’s body and blood in the Lord’s Supper, essentially collapsing his Eucharist into his Epiclesis.

Dionysius of Alexandria (256 A.D.)

A member of Dionysius’ congregation was concerned that his baptism was invalid, but Dionysius was not inclined to rebaptize him. In his summary, Dionysius says “I should not dare to renew from the beginning one who had heard the giving of thanks (εὐχαριστίας) and joined in repeating the Amen; who had stood by the table and had stretched forth his hands to receive the holy food (τῆς ἁγίας τροφῆς) ; and who had received it, and partaken for a long while of the body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ” (Eusebius, Church History, Book 7, 9.4; Migne, P.G. 20, 656). Here Dionysius reflects the Biblical liturgy of a Eucharist, an “Amen,” a Consecration and a Meal. As we have noted, the language is consistent with that of his predecessor (Origen of Alexandria) and his contemporary (Cornelius of Rome) who both describe the bread being consecrated after being distributed into the hands of the communicants (Origen, Against Celcus, Book VIII, 33; Eusebius, Church History, Book 6, 43.18-19; Migne, P.G. 20, col 627, n53). Additionally, as we saw in the Didache (chapter 9), Irenæus (Against Heresies, Book IV, 18.5) Hippolytus (Anaphora 5-6), Tertullian (de Spectaculis (The Shows) 25), Firmilian (Epistle 74 to Cyprian, 9), and Cyprian (the Lapsed, 26), the food is “heavenly,” “holy,” and “sanctified” merely by being set aside as a tithe, and there is no cause for interpreting ἁγίας τροφῆς in any other way here with Dionysius. Even in view of that historical and contextual data, the translators opted to render “the holy food” in Greek as “the blessed food” in English, giving the impression that “the giving of thanks (εὐχαριστίας)” was itself the Consecration, resulting in an offering of Consecrated food.

That assumption essentially collapses Dionysius’ Eucharist offering into his Epiclesis to give the impression that the meal had been Consecrated by being Eucharisted.

Gregory Nazianzus the Elder (c. 276 – 374 A.D.)

The Elder’s eucharist was clearly a tithe offering to provide for the widow the orphan and the stranger, and his readiness to provide for the poor was, as his son reports, a greater sacrifice than “the mere offering,” indicating that the Elder’s Eucharist offering was indeed a provision for the poor, not a sacrifice of Christ’s body and blood. During his Eucharist offering, his wife’s thoughts were occupied with “the misfortunes of strangers,” indicating that the Eucharist was offered to provide food for the stranger, not as a propitiatory sacrifice of Christ’s body and blood. Thus, his “customary words of thanksgiving” would have been consistent with the customary words of thanksgiving for the first-fruits of the harvest to provide for the poor, as we have seen for the 300 years preceding Gregory of Nazianzus the Elder. Nevertheless, de Billy added a textual notation (†) to the Latin “Eucharistiæ verba” to indicate that the “customary words of thanksgiving” must have been in reference to the Consecration, and Migne followed him, leaving the impression that Nazianzus’ Eucharist was consecratory, essentially collapsing his Eucharist into his Epiclesis.

Follow

Follow

Timothy:

In your final installment on the RCC Eucharistic Rite, you conclude:

“And thus, a very simple liturgy prevailed for three hundred years: A Eucharist. An Amen. An Epiclesis. At the end of the 4th century, the order changed and the Epiclesis was moved before the Eucharist offering, which changed a simple tithe offering for the poor into a sacrifice of consecrated bread and wine. Thus was born the abominable Roman Catholic liturgical sacrifice of Christ’s body and blood.”

If you are calling the current RCC Eucharist an abomination, then you are calling the first three hundred years of the Christian eucharist an abomination as well. You say the order in the Liturgy of the Eucharist in the early church is as follows:

[Eucharist, Amen, Epiclesis}.

Here is the RCC rite in three parts with each part ending in an AMEN:

Offertory–AMEN-[Eucharist–AMEN-Epiclesis]–AMEN

This standard order of liturgy can be found online here:

https://www.universalis.com/static/mass/orderofmass.htm

As you can plainly see, the order has not changed and the Epiclesis was not moved before the Eucharist offering, and did not change a simple tithe offering for the poor into a sacrifice of Christ’s body and blood.

What did happen later was that the offertory, thanksgiving, and consecration were called, as a combination, the Eucharistic Rite or the Liturgy of the Eucharist. That does not constitute an abomination. It would be an abomination if the Body and Blood of Christ, which was already sacrificed 2000 years ago, was re-sacrificed by the RCC. But the true abomination would be if you thought we really had the power to do that. The Real Presence of Christ, put there in the consecrated bread and wine by the Holy Spirit, has already been sacrificed and is impossible for us to sacrifice again.

Nick,

In the early church, the Eucharist was the tithe offering before the consecration. In the link you provided, the Eucharist is the offering of Christ’s body and blood after the Consecration:

So, no, the rite you provided is not the same as that of the first three centuries.

You have provided several Amens as listed in the modern rite, but as I have several times pointed out to you, only one can be traced to antiquity. The Roman Catholic Encyclopedia says that the additional Amens throughout the liturgy can only be traced to the latter part of the 4th century, and only one can actually be traced earlier than that. While the encyclopedia assumes that the ancient apostolic Amen is the one spoken after the consecration, the early evidence shows that the ancient apostolic Amen is the one spoken after the Eucharist offering before the consecration.

In any case, you have repeatedly provided the modern canon of the mass and alleged that it retains the same order and substance as the liturgy of the first three centuries, but the Roman Catholic Encyclopedia shows the ignorance with which you make that claim:

If by Rome’s own confession “the Eucharistic prayer was fundamentally changed and recast at some uncertain period between the fourth and the sixth and seventh centuries” and “a great transformation was made in the Roman Canon” between 400 and 500, there is simply no way the current Roman eucharistic rite could possibly be the same as that of the first three centuries.

All that remains is to evaluate the actual evidence of the first three centuries, as I have done. The Amen repeatedly occurs between the Eucharist and the Epiclesis. As such, the Eucharist offering of the early church was a tithe of unconsecrated food for the widow, the orphan and the stranger, and concluded with an Apostolic Amen. It was not a sacrifice of the body and blood of Christ. At the end of the 4th century, the Eucharist Offering as moved to a point after the Epiclesis, an the Amen after the Eucharist began to be understood as an affirmation of the consecration instead of an affirmation of the thanksgiving. The evidence is what it is and I have done my best to represent it fairly.

…and…

Nick argues that the RCC’s liturgy is the ancient liturgy with extra Amens, no different than, say, the way that Protestants end all prayer with Amen. And—most importantly—there is still an Amen between the eucharist offering and the epiclesis, so it doesn’t make sense to say that there is no Amen between them, because there is one, just as there was in the ancient liturgy.

At the link Nick provided, the order is as follows:

Nick gave this explanation:

I can make no sense of this claim.

The Eucharistic prayer includes both the blessing of the tithe and the Consecration. Now there are two Amens in the prayer, but these are optional and spoken only by the priest. So, despite the seven required liturgical Amens, there is no Amen separating them.

As a reminder, the Vatican declares this:

On one hand, the tithe offering is the Eucharist offering separated by an Amen from the epiclesis. On the other hand, the tithe offering is a simple act separated from the eucharist and epiclesis. These cannot both be true.

DR says: “The Eucharistic prayer includes both the blessing of the tithe and the Consecration. Now there are two Amens in the prayer, but these are optional and spoken only by the priest. So, despite the seven required liturgical Amens, there is no Amen separating them.”

And yet those AMENS are there and are in between the thanksgiving and the epiclesis. And as Tim notes “amen” is an ending. And I noted this earlier in my posts for “Collapse” Part 2 blog.

You also say: “As a reminder, the Vatican declares this:

‘The Eucharist is the very sacrifice of the Body and Blood of the Lord Jesus which he instituted to perpetuate the sacrifice of the cross throughout the ages until his return in glory.’

Absolutely right. What is wrong with utilizing Jesus’s sacrifice on the Cross to sanctify the offertory and to consecrate the bread and wine? That is why He instituted the sacrament so that we, who are in Christ and He in us, can apply His once and for all perfect sacrifice 2000 YEARS AGO (His resurrection did not “un-sacrifice” Him–he still has the scars to prove it) when we offer ourselves as a living sacrifice TODAY. We offer our tithes and our very selves through Him,(John 14:6) with Him,(Matthew 18:20) and in Him (John 14:20). This is why we stand and proclaim AMEN!

We DO NOT re-sacrifice Christ. It’s your problem if you think that is an abomination.

Tim,

One important point that you had mentioned on the Diving Board podcast is that the words of consecration were sometimes said AFTER the Eucharist was handed out. If the words of Consecration were any part of the Eucharistic Sacrifice (as Roman Catholics would conclude) wouldn’t that require that all the laity be considered Sacerdotal priests as well according to Roman Catholicism?

Maybe this has been pointed out in the previous articles / comment sections… I haven’t read through all of the articles and exchanges as of yet, but this was one of my initial thoughts from the first podcast in this series.

I truly appreciate your work Tim!

-Destin

That is a good point, Destin. The series is largely limited to the propensity of the scholars to collapse the ancient Eucharist into the ancient Epiclesis, rather than the implications of the order of the ancient liturgy to the communicant. But yes, it is an important point: the fact that the consecration could be (and in some cases was) spoken after the bread and wine had already been distributed into the hands of the communicant is inconsistent with a supposed early realization of the sacrificial nature of the Supper itself, or of a special priestly caste that handled the Lord’s body sacrificially. This is why it is so significant that origins of priestly celibacy and of different priestly vestments, also originate at the end of the 4th century‚ the same time when the priestly caste suddenly “realized” they were sacrificing Christ’s body and blood.

If God seeks only to unify, and the Devil only to divide, how then do you reconcile with there being one holy and apostolic Catholic Church, and many tens of thousands of protestant denominations, some of which split from one another over the color of the front doors?

Have you gone so deep into your theological journey that you have forgotten the basic and most simple marks of God and of the devil?

Jacob, if division is the mark of the devil, how do you explain Luke 12:51, “ “Suppose ye that I am come to give peace on earth? I tell you, Nay; but rather division:”

Are you saying Jesus is the devil?

Jacob–

Tim is asking a trick question.

In Luke 12:51, Jesus divides men–those of God from those of the devil. In John 17:11ff Jesus seeks for unity so that the believers will be as one in Him–one holy, catholic, and apostolic church.

Timothy says:

“This is why it is so significant that origins of priestly celibacy and of different priestly vestments, also originate at the end of the 4th century‚ the same time when the priestly caste suddenly “realized” they were sacrificing Christ’s body and blood.”

You seem to infer here that the RCC sacrifices Christ’s Body and Blood in the Mass. I would also assume that you believe this happens at every Mass–re-sacrificing Christ over and over again–even though you have not said it in those words. I’ll rephrase the question:

“How do you explain the procedure of sacrificing Christ’s Body and Blood that you infer we Catholics do at every Mass?”

Tim,

Your quotation from Book 7 is cited incorrectly. It is from Book 7, “9.4”, not “11.5-6.” I don’t know about the Migne quotation, whether that is right or wrong.

Peace,

DR