We continue this week with our analysis of the works of Ignatius of Antioch (d. 107 AD). Last week, we assessed the methodology of a typical Roman Catholic apologist who claims to have been “red pilled” into the truth by his writings. Mr. Joshua T. Charles, former White House speech writer, former Protestant and now apologist, reminds his Twitter followers repeatedly that he has read “tens of thousands of pages” of the Early Church Fathers and was surprised to find Roman Catholicism “absolutely everywhere.” As we showed last week, however, Mr. Charles is either highly selective in his reading or highly selective in his use of data—either rejecting that which contradicts his preconceptions, or reinterpreting contrary data as if it supported his position, and in many cases naïvely receptive of data known to be spurious, redacted and fraudulent.

As we noted last week, Mr. Charles claimed that he was surprised to find “profoundly [Roman] Catholic doctrine” in Ignatius’ letters, “point by point.” Of the ten “points” he identified, we will address two today:

1. The Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist;

3. Christian worship = the sacrifice of the Eucharist;

By way of reminder, Roman Catholicism teaches that when pronouncing the words “This is My body” and “This is My blood” over the bread and wine, Jesus was literally turning them into His body, blood, soul and divinity by a process called “transubstantiation.” And because in Roman Catholicism the Lord’s Supper is a sacrifice, they believe that Jesus taught the Apostles to offer the transubstantiated bread and wine to the Father for our sins. And because the consecrated bread and wine are alleged to be Jesus’ body, blood, soul and divinity, they are worshiped. The “Jesus” that is alleged to be “really present” in them is called by them “our Eucharistic Lord.” That is the god they serve and worship.

Mr. Charles’ compilation of ancient support for the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist may be found here. His first three Patristic sources in support of the doctrine are all from Ignatius:

I have no taste for corruptible food nor for the pleasures of this life. I desire the bread of God, which is the flesh of Jesus Christ, who was of the seed of David; and for drink I desire his blood, which is love incorruptible. (To the Romans, 7)

Take note of those who hold heterodox opinions on the grace of Jesus Christ, which have come to us, and see how contrary their opinions are to the mind of God…They abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer because they do not confess that the Eucharist is the flesh of our Savior Jesus Christ, flesh that suffered for our sins and that the Father, in his goodness, raised up again. They who deny the gift of God are perishing in their disputes. (To the Smyrnæans, 6-7)

Take heed, then, to have but one Eucharist. For there is one flesh of our Lord Jesus Christ, and one cup to [show forth] the unity of His blood; one altar; as there is one bishop, along with the presbytery and deacons, my fellow-servants: that so, whatsoever you do, you may do it according to [the will of] God. (To the Philadelphians, 4)

The last citation, To the Philadelphians, is also the only quote from Ignatius that Mr. Charles provides in support of the Sacrifice of the Eucharist. As such, we will discuss both constructs at once: the Real Presence and the Sacrifice of the Mass.

Mr. Charles provides little commentary on these passages except to offer them as proof that “the Church Fathers” supported the doctrine of the Real Presence. Such language as “the bread of God … is the flesh of Jesus,” and “the Eucharist is the flesh of our Savior” and “one Eucharist … one flesh” are ostensibly so obviously Roman Catholic that we are supposed to accept them without context or explanation. And that is the problem: Mr. Charles doesn’t think these passages need to be expounded because they are so obvious. Thus, to the gullible and the ignorant the citations are convincing on their face. But the context and content of his letters tell a different story.

The Native Context of Ignatius’ Letters

What the typical Roman Catholic apologist does not understand is that Ignatius did not write these words in a high medieval liturgical context. He wrote them in the early second century when the ravages of Gnosticism were spreading throughout Asia Minor (modern day Turkey). The Roman Catholic apologist is of course aware of the Gnostic onslaught, but that is the end of his practical knowledge. Instead of understanding Ignatius in that context, the Roman Catholic apologist assumes Ignatius went to war with the second century Gnostics by wielding medieval liturgical constructs. He most certainly did not.

To understand Ignatius we must first understand the threat he was facing, observe how he reacted to it, and understand why he reacted the way he did. To that end we shall first examine the doctrinal context of his letters and second, the prevailing liturgical context at the time of his writing. What we shall find when we examine his letters in their native context is that he had no knowledge of the “Real Presence” of Christ in the Eucharist, and that none of the passages invoked by Mr. Charles so much as hint at it — no not even “the Eucharist is the flesh of our Savior.”

The Doctrinal Context

The Spread of “Peter’s” Apocalypse

In the late first century, the Gnostic Apocalypse of Peter, was making inroads into the young churches in Asia Minor. “Peter’s” Apocalypse warned against “bishops” and “deacons” who perpetrated the “false doctrine” of the incarnation, claiming “falsely” to have been established by divine institution. Against these “bishops” and “deacons” the sheep would eventually need to rebel. We shall come back to that point next week.

In addition to those derogatory comments about bishops and deacons, the Apocalypse of Peter claimed that the person upon whom people gazed at the crucifixion was not the Christ, for the “one into whose hands and feet they [drove] the nails” was not really Jesus, for the Savior cannot be “susceptible to suffering.” His incorporeal body had not undergone any real passion in the crucifixion at all:

… he whom they crucified is the first-born … But he who stands near him is the living Savior … whom they seized and released … the one susceptible to suffering … is the substitute. But what they released was my incorporeal body. But I am the intellectual Spirit filled with radiant light. (Apocalypse of Peter)

Flesh and Spirit

Ignatius was indignant on behalf of the scattered churches, insisting in his letters that Jesus Christ was truly “nailed to the cross … both in the flesh and in the spirit” (Smyrnæans, 1), and that everyone witnessed it, for He had been crucified “in the sight of beings in heaven, and on earth, and under the earth” (Trallians, 9). In Christ, the “impassible” (incapable of suffering) “became passible (capable of suffering) on our account” (Polycarp, 3). The Person on the cross was the Savior, and He had truly suffered “both in the flesh and in the spirit.”

As proof, Ignatius appealed to Jesus’ own testimony after His Resurrection:

Behold my hands and my feet, that it is I myself: handle me, and see; for a spirit hath not flesh and bones, as ye see me have. (Luke 24:39)

But because the Apocalypse of Peter had claimed the resurrected Christ was an “incorporeal … spirit”, Ignatius tailored Luke 24:39 to rebut that very specific claim, substituting “I am not an incorporeal spirit” for “a spirit hath not flesh and bones”:

For I know that after His resurrection also He was still possessed of flesh, and I believe that He is so now. When, for instance, He came to those who were with Peter, He said to them, “‘Lay hold, handle Me, and see that I am not an incorporeal spirit.'” And immediately they touched Him, and believed, being convinced both by His flesh and spirit. (Smyrnæans, Chapter 3)

It is in that context that Ignatius wrote his letters to the young churches in Asia minor. Jesus’ possession of both flesh and spirit was his constant theme, and that construct manifested repeatedly in his letters to the churches — even when he was not talking about Jesus:.

There is one Physician who is possessed both of flesh and spirit; (Ephesians, 7)

I commend the Churches, in which I pray for a union both of the flesh and spirit of Jesus Christ, (Magnesians, 2)

I salute you from Smyrna, together with the Churches of God which are with me, who have refreshed me in all things, both in the flesh and in the spirit. (Trallians, 12)

to those who are united, both according to the flesh and spirit (Romans, greeting)

May the Lord Jesus Christ honour them, in whom they hope, in flesh, and soul… (Philadelphians, 7)

And immediately they touched Him, and believed, being convinced both by His flesh and spirit. (Smyrnæans, 3)

I salute the house of Tavias, and pray that it may be confirmed in faith and love, both corporeal and spiritual. (Smyrnæans, 13)

Maintain your position with all care, both in the flesh and spirit. (Polycarp, 1)

Speak to my sisters, that they love the Lord, and be satisfied with their husbands both in the flesh and spirit. (Polycarp, 5)

These are but a sampling of his many references to “flesh and spirit” — or “flesh and soul,” or “corporeal and spiritual” — in his letters. As is evident, it was a persistent theme, even when he was emphasizing matters utterly unrelated to the Incarnation and the Resurrection (e.g., his own refreshment from the Trallians, the marital and household relations of the Smyrnæans).

“Flesh” vs. “Body”

So determined was Ignatius in his refutation of the Gnostic error, that while Paul exhorted the Christians to “salute every saint in Christ Jesus” (Philippians 4:21), Ignatius could not leave it at that. He also saluted them in His flesh, blood, passion, resurrection and corporeal and spiritual unity:

“I salute … all of you … in the name of Jesus Christ, and in His flesh and blood, in His passion and resurrection, both corporeal and spiritual.” (Smyrnæans, 12)

And because the Apocalypse of Peter had claimed, paradoxically, that the resurrected Jesus possessed an “incorporeal body,” Ignatius largely avoided the use of the word “body” in his letters. To refute the Gnostics, it was not sufficient merely to claim that Jesus possessed a body, for the Gnostics conceded as much, at least in some impossible “incorporeal” sense. No, the counterargument had to be that Jesus possessed flesh.

[N.B.: Please note that Tertullian raises exactly this issue in his argument against the gnostic Marcion: “For no blood can belong to a body which is not a body of flesh. If any sort of body were presented to our view, which is not one of flesh, not being fleshly, it would not possess blood. Thus, from the evidence of the flesh, we get a proof of the body, and a proof of the flesh from the evidence of the blood.” (Against Marcion, Book 4 40)]

Remarkably, in his seven genuine letters, Ignatius used the word “body” only four times — thrice to refer to himself (Romans, 4 & 5) and once to refer to Jesus Who was “possessed of a body” (Smyrnæans, 5). And even then, he did so only after twice repeating the refrain that “He was still possessed of flesh … being possessed of flesh” (Smyrnæans, 3). He used “body” just four times but “flesh” “fleshly,” or “corporeal” 39 times.

Even when alluding to a passage of Scripture that explicitly used the word “body,” Ignatius was disinclined to repeat the term, substituting “flesh” instead, to make his point. Referring to the unity of the body, Paul said

The cup of blessing which we bless, is it not the communion of the blood of Christ? The bread which we break, is it not the communion of the body of Christ? For we being many are one bread, and one body: for we are all partakers of that one bread. (1 Corinthians 10:16-17)

How does Ignatius summarize this point? That there is “one body” and “one cup”? That there is “one bread” and “one cup”? Nay, neither. He says instead that there is one flesh and one cup:

Take heed, then, to have but one Eucharist. For there is one flesh of our Lord Jesus Christ, and one cup to [show forth ] the unity of His blood (Philadelphians, 4)

This is valuable information to us for several reasons. Ignatius’ lavish and indiscriminate use of “flesh” indicates that his focus was not on arguing for transubstantiation but against the Gnostic characterization of Christ as a spirit only. We note, for example, that he never claims that the Eucharist is “the flesh and spirit” of Christ, a combination he insists upon whenever he refers to the Lord’s passion, which, according to Roman Catholicism, the Eucharist makes present. For this reason we can hardly entertain an argument for transubstantiation based on his use of “flesh” to describe the Eucharist, especially when in another letter he says “faith … is the flesh of the Lord” and “love … is the blood of Christ” (Trallians, 8).

What is more, this knowledge of Ignatius’ disinclination to use “body” illuminates his “confession” that the Eucharist is “the flesh of Christ,” by which he means to refer to “the body of Christ.” This becomes extremely significant in our discussion of the liturgical context of his letters, to which we now turn.

The Liturgical Context

The Liturgical Dismissal

As we observed in our post The Apostolic “Amen” and our series, Collapse of the Eucharist, because Jesus had given thanks to His Father immediately before instituting the Supper, only believers were allowed to attend the offertory. The unbeliever, the catechumen, the backslider and anyone at odds with his brother, was therefore excused from the service before the tithe offering. Jesus said gifts ought not be offered in discord (Matthew 5:23-24), and Paul warned against coming together in strife and divisions (1 Corinthians 11:17-18). The early Church took these admonitions seriously, and therefore prohibited anyone from participating in the tithe offering unless he was a professing believer and was not harboring resentment or a spirit of discord against the brethren.

“[L]et no one that is at variance with his fellow come together with you, until they be reconciled, that your sacrifice may not be profaned” (Didache, 14 (c. 100 AD)). Only he “who believes that the things which we teach are true …. and who is so living as Christ has enjoined” is allowed to participate in the thanksgiving (εὐχαριστίᾳν) offerings (Justin Martyr, First Apology 66 (150 AD)). The “offering [of] the first-fruits” must be made “in a pure mind, and in faith without hypocrisy,” which is why the Jews (who deny Jesus is the messiah) and the heretics (who deny Jesus came in the flesh) cannot offer acceptable sacrifices (Irenæus, Against Heresies IV.18.4 (189 AD)). Because new converts were finally allowed to remain for the oblations, they were instructed to bring their own Eucharist with them on the day of their baptism (Hippolytus, Anaphora 20 (215 AD)). Those recently found in sin were not allowed to stay for the offerings until their time of repentance was complete (Nicæa, Canon 11 (325 AD)). Bishop Julius of Rome wrote that Catechumens — those in training, but yet unbaptized — were dismissed from the weekly service before the offerings, “[f]or if there were catechumens present, it was not yet the time for presenting the oblations” (Athanasius, Apology Against the Arians, I.28 (341 AD)). Ambrose of Milan was careful to begin “offering the oblation” only after “the Catechumens were dismissed” (Ambrose, Epistle 20 4-5 (385 AD)).

It is not common knowledge to Roman Catholics, but their preferred term for the Supper, “Sacrifice of the Mass,” is actually a misnomer. The Latin, “Missa,” means “dismissal,” and is transliterated into English as “Mass.” The Catholic Encyclopedia concedes Rome’s institutional ignorance on its meaning, guessing that “Mass” must refer to the dismissal of believers after the Supper. That would make the Supper the “Sacrifice of the Mass” because of people being dismissed after it. However, a cursory analysis of the early liturgy reveals the meaning plainly: the Eucharist, which is to say the tithe offering, came to be called the sacrifice of the dismissal because unbelievers and backsliders were dismissed before the Eucharist offering — so important was it to our ancient brethren that the offertory be untainted by strife and unbelief. “Sacrifice of the Mass” thus became the term that was used to describe the tithe offering. The Roman etymology is incorrect and highly misleading. The Eucharist was called Sacrifice of the Dismissal because unbelievers, heretics, the backslidden and the catechumen were dismissed before the tithe, not because believers were dismissed after the Supper.

The Eucharist as a Tithe Offering

As we highlighted in The Apostolic “Amen”, the Eucharist of the Ancient church was the tithe offering to care for the poor. Through the prophet Malachi, the Lord condemned the unacceptable burnt offerings of the Jews, foretelling a day when “in every place incense shall be offered unto my name, and a pure offering … among the heathen” (Malachi 1:10-11). The apostles left instructions that sacrifices must and would continue under the New Covenant, but these new sacrifices would take the forms of “praise … the fruit of our lips giving thanks” (Hebrews 13:15), doing good works and sharing with others (Hebrews 13:16), “spiritual sacrifices” (1 Peter 2:5), providing for those in need (Philippians 4:18), and “your bodies a living sacrifice” (Romans 12:1). Such sacrifices are “holy” and “acceptable” (Romans 12:1, 1 Peter 2:5) and well-pleasing to the Lord (Philippians 4:18, Hebrews 13:16). A new temple of living stones had been constructed so that these new sacrifices would continue (1 Peter 2:5).

The early church understood these apostolic instructions as the fulfillment of Malachi’s prophecy, and included thank offerings — εὐχαριστία (eucharistia) — in the liturgy. The Sunday gathering was the venue for those offerings, as tithes of the harvest were collected and distributed to “orphans and widows and…all who are in need” (First Apology, 67 (150 AD)). According to Irenæus (189 AD), “the very oblations” of the church consisted of the tithes of the Lord’s people: Christians “set aside all their possessions for the Lord’s purposes,” just as the widow had in the Gospels (Mark 12:42, Luke 21:2), “offering the first-fruits” to care for the needy, hungry, thirsty, naked, and poor (Against Heresies, Book IV.18). Tertullian believed the sacrifices prophesied by Malachi were fulfilled in “the ascription of glory, and blessing, and praise, and hymns”and “simple prayer from a pure conscience” (Against Marcion, Book 4 1). He thought the believer “was bound to offer unto God in the temple a gift, even prayer and thanksgiving in the church through Christ Jesus” (Against Marcion, Book 4 9). The believer must be present for “both the participation of the sacrifice” and for the “reception of the Lord’s Body” (Tertullian, On Prayer 19). However, since he understood the Supper to occur only after the bread had been distributed and consecrated (Against Marcion, Book 4 40), he clearly saw the Eucharist as “a gift” along with “the sacrificial prayers” that were offered before the consecration. Athanasius understood the sacrifice of Malachi 1:11 to be fulfilled in thanksgiving, “a joyful noise,” “praise and prayer” (Athanasius, Festal Letter 11) when we “take up our sacrifices, observing distribution to the poor” (Athanasius, Festal Letter 45). For this reason, the early Eucharist offering occasionally included a banquet of unconsecrated food, a love-feast, in order for the poor and the hungry to be satisfied. Tertullian confirms that the poor and hungry were fed at the love-feast: “with the good things of the feast we benefit the needy,” (Apology, 39) and “the Eucharist [is] to be eaten at meal-times” (De Corona, 3). The early Church clearly offered the Eucharist sacrifice but it is not what Roman Catholicism imagines. The Eucharist, rather, was the predecessor to our modern offertory.

The Apostolic “Amen”

Consistent with Paul’s explanation in 1 Corinthians 14:16, the ancient church included a liturgical exclamation, saying “Amen at thy giving of thanks” (1 Corinthians 14:16), or literally, saying “Amen” at thy Eucharist. Ancient believers incorporated that liturgical admonition into the liturgy. Thus, the ancient Church concluded its Eucharistic oblation with a corporate “Amen” before the bread and wine were consecrated for the Supper. In other words, in the ancient Church, what was offered was not consecrated, and what was consecrated was not offered. As such, there was no liturgical offering of the body and blood of Christ in the ancient Church.

Of this corporate “Amen” to conclude the tithe but before the consecration, the early writers expound repeatedly: Justin Martyr (c. 150 AD) wrote that “all the people present express their assent by saying Amen” immediately after the officiant “offers prayers and thanksgivings (εὐχαριστίας, eucharistias),” the “Amen” being spoken, quite notably, before the consecration is uttered (First Apology 65, 67). Irenæus of Lyons (189 AD) described the “Amen, which we pronounce in concert” (Against Heresies 1 14.1), and had the Eucharist offering occurring prior to the consecration (Against Heresies 1 13.2), implying that the “Amen” to conclude the oblation would have been spoken prior to the consecration for the Supper — a liturgy he confirmed later in Against Heresies (Against Heresies 5 2.3), and again in Fragment 37. Tertullian of Carthage (208 AD) considered the Eucharist to be “a gift” and “the sacrificial prayers” that were offered (Against Marcion, Book 4 9). Thus, when he wrote of the “Amen” a person speaks with regard to the “sanctum protuleris” (Migne, P.L. vol I, col 657) or literally, “the holy offering” (The Shows 25), he placed the “Amen” between the offering and the consecration, indicating the completion of the Eucharistic sacrifice before the bread and wine were consecrated. Dionysius of Alexandria placed the “Amen” immediately following “the giving of thanks” but before the consecration and the supper (Eusebius, Church History VII.9.4). Athanasius of Alexandria placed the “Amen” immediately following the “pure sacrifice” of “praise and prayer” after which “all men in common send up a song of praise and say, Amen” (Festal Letter 11), identifying the sacrifices as the Church’s “distribution to the poor” (Athanasius, Festal Letter 45).

In our assessment of the ancient liturgy, it is rather significant to know that the “Amen” came after the oblation was complete, but before the consecration was spoken over the bread and wine. It utterly eliminates any possibility of an ancient offering of Christ’s body and blood for the simple reason that the Eucharist offering was ended, and the “Amen” was spoken, before anyone had consecrated any bread wine for the Supper.

The Ancient Consecration

In the Ancient Church, the bread and wine of the Supper were consecrated merely by “confessing” Jesus’ words over them. That consecration — “this is my body” (1 Corinthians 11:24) and “this is my blood” (Matthew 26:28) — is attested by Justin, (First Apology, 66), Irenæus (Against Heresies IV.18), Clement (Paedagogus, 2.2), and Tertullian (Against Marcion, 4, 40). According to Irenæus, “the cup likewise, which is part of that creation to which we belong, He confessed (confessus) to be His blood” (Against Heresies, IV.17.5 (Migne, PG 7, 1023)) and He “acknowledged (confessed (confitebatur)) the bread to be His body” (Against Heresies IV.33.2 (Migne, PG 7, 1073). The consecration was simply “to confess” Jesus’ original words of institution — “this is My body” — over the bread. Notably, that consecration did not occur until after the oblation, or thank offering, was already complete. Thus, it was impossible in the ancient liturgy to offer consecrated bread and wine.

The Ancient Liturgical Order

Once the Eucharistic offering was complete, and the people had exclaimed, “Amen,” some of that bread and wine from the Eucharistic offertory was then distributed for the Supper. As such, the Supper, too, came be called “The Eucharist.” But that Apostolic “Amen” had established a separating wall such that what was offered had not been consecrated, and what was consecrated was not then offered. And thus, it is indeed true that the Early Church offered the Eucharist (as a tithe offering), and it is also true that the early church celebrated the Eucharist as a Supper of Consecrated bread and wine — Jesus’ Body and Blood. But the Eucharist they sacrificed was not consecrated, and the consecrated Eucharist they ate was not sacrificed.

This liturgical order is attested in Justin Martyr’s First Apology (150 AD) in which, only believers are allowed to attend, the Eucharist is offered and completed with a corporate Amen, and only then is the food is distributed and consecrated for the Supper:

Dismissal: only he who “has assented to our teaching” is allowed to join the brethren “in order that we may offer hearty prayers in common for ourselves” (First Apology 65) “and thanksgiving for all things wherewith we are supplied” (First Apology, 13).

Eucharist as an Offering: “the president of the brethren … offers thanks at considerable length for our being counted worthy to receive these things at His hands.”

Amen: “And when he has concluded the prayers and thanksgivings, all the people present express their assent by saying Amen.”

Eucharist as the Supper: “And when the president has given thanks, and all the people have expressed their assent, those who are called by us deacons give to each of those present to partake of the bread and wine mixed with water over which the thanksgiving was pronounced, and to those who are absent they carry away a portion.” (Justin Martyr, First Apology 65)

Irenæus (189 AD), too, attests to this order. Note that Irenæus says the Lord “gave directions” to offer “first-fruits”, and after the offering celebrated the meal, and thus “taught the oblation of the new covenant.” But the meal was not the oblation. The offering of “first fruits” (Eucharist) before the consecration is the only “oblation” Irenæus thought Jesus taught them:

Dismissal: “it behooves us to make an oblation to God, and in all things to be found grateful to God our Maker, in a pure mind, and in faith without hypocrisy, in well-grounded hope, in fervent love, offering the first-fruits of His own created things” (Against Heresies 4.18.4)

Eucharist as an Offering: “Again, giving directions to His disciples to offer to God the first-fruits of His own, created things — not as if He stood in need of them, but that they might be themselves neither unfruitful nor ungrateful — He took that created thing, bread, and gave thanks … ” (Against Heresies 4.17.5) … “And the Church alone offers this pure oblation to the Creator, offering to Him, with giving of thanks, [the things taken] from His creation.” (Against Heresies 4.18.4)

Amen: [“Amen, which we pronounce in concert”] (see Against Heresies 1.14.1)]

Eucharist as the Supper: … and said, “This is My body.” And the cup likewise, which is part of that creation to which we belong, He confessed to be His blood, and taught the new oblation of the new covenant; (Against Heresies 4.18.4)

Tertullian (215 AD) also attests to this very same liturgical order:

Dismissal: The “pure offering” must be “simple prayer from a pure conscience” (Against Marcion, Book 4 1), implying a dismissal of the unrepentant and backslidden before the offering.

Eucharist as an Offering: We are “bound to offer unto God in the temple a gift, even prayer and thanksgiving in the church through Christ Jesus” (Against Marcion, Book 4 9).

Amen: The people say “Amen” over the “sanctum protuleris” (Migne, P.L. vol I, col 657) or literally, “the holy offering” (The Shows 25)

Eucharist as a Supper: “Then, having taken the bread and given it to His disciples, He made it His own body, by saying, “This is my body,” that is, the figure of my body.” (Against Marcion, IV, 40)

Origen (248 AD), while mentioning no “Amen,” nevertheless attests to this same order, placing the oblation prior to the consecration, and attesting to the strict requirements for participating in the Eucharist offering:

Dismissal: “We must surely live, and we must live according to the word of God, as far as we are enabled to do so. And we are thus enabled to live, when, “whether we eat or drink, we do all to the glory of God;” and we are not to refuse to enjoy those things which have been created for our use, but must receive them with thanksgiving to the Creator.”

Eucharist as an Offering: “But we give thanks to the Creator of all, and, along with thanksgiving and prayer for the blessings we have received…”

Eucharist as the Supper: “… we also eat the bread presented to us; and this bread becomes by prayer a sacred body, which sanctifies those who sincerely partake of it.” (Against Celsus, VIII.33)

Dionysius of Alexandria (256 AD), too, attested to this same liturgical order:

Dismissal: [the succeeding conversation occurs in the context of a communicant who did not know if he was validly baptized, and therefore whether he could participate in the Eucharist]

Eucharist as an Offering: “For I should not dare to renew from the beginning one who had heard the giving of thanks…

Amen: ” … and joined in repeating the Amen; …”

Eucharist as the Supper: “… who had stood by the table and had stretched forth his hands to receive the blessed food; and who had received it, and partaken for a long while of the body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ. (Eusebius, Church History VII.9.4)

Athanasius of Alexandria (d. 373 AD) held to the same liturgy:

Dismissal: “faith and godliness … such meditation and exercise in godliness, being at all times the habit of the saints, is urgent on us at the present time, when the divine word desires us to keep the feast with them if we are in this disposition.” (Festal Letter 11, 9-11)

Eucharist as the Sacrifice: “the sacrifice is not offered in one place, but ‘in every nation, incense and a pure sacrifice is offered unto God.’ So when in like manner from all in every place, praise and prayer shall ascend to the gracious and good Father …” (Festal Letter 11, 9-11) “Let us all take up our sacrifices, observing distribution to the poor” (Festal Letter 45).

Amen: “… when all men in common send up a song of praise and say, Amen” (Festal Letter 11, 11).

Eucharist as the Supper: “Therefore, because He was sacrificed, let each of us feed upon Him, and with alacrity and diligence partake of His sustenance;” (Festal Letter 11, 14)

We offer these several examples of the early liturgy because it is important to demonstrate that ancient, consistent liturgical order: Dismissal, Eucharist as an Offering, Amen, Consecration & Eucharist as the Supper. It was the standard liturgy for the first three centuries of Christianity, and it is evident from that liturgy that the Eucharist oblation, the original Sacrifice of the Mass, was offered prior to the consecration and thus did not consist of Christ’s body and blood but rather of first-fruits from the harvest to feed the poor. And therefore, when we examine Ignatius’ early second century liturgy, we should expect to find that same liturgical order. Indeed we do.

Ignatius’ Eucharistic Liturgy

There is very little evidence available to us from Ignatius, but we are nevertheless able to reconstruct this very same ancient liturgy from him. In his letter to the Smyrnæans we see the Dismissal, the Eucharist as a tithe offering, the Consecration and the Eucharist as a Supper. To do so first we must correct the disservice the Roman Catholic Apologist performs in his arguments, for he removes from Ignatius a point of profound significance: that the Eucharist he has in mind is the tithe offering.

The reader is invited to scroll back to the top to read Mr. Charles citation from Ignatius’ letter to the Smyrnæans, and observe the ellipsis in his citation. The Roman Catholic apologist always leaves out that critical piece of evidence because he does not know what it means. But that piece of evidence is Ignatius’ contextual cue that the Eucharist he has in mind is the tithe offering for the poor. Here is the full citation from Ignatius, with Mr. Charles’ omission in brackets:

Take note of those who hold heterodox opinions on the grace of Jesus Christ, which have come to us, and see how contrary their opinions are to the mind of God. [They have no regard for love; no care for the widow, or the orphan, or the oppressed; of the bond, or of the free; of the hungry, or of the thirsty.] They abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer because they do not confess that the Eucharist is the flesh of our Savior Jesus Christ, flesh that suffered for our sins and that the Father, in his goodness, raised up again. They who deny the gift of God are perishing in their disputes. (To the Smyrnæans, 6-7)

The significance of the omission is profound, for it reveals to us that “the Eucharist” Ignatius has in mind here is the tithe offering for the poor. The “Eucharist” from which the heretics abstained was the tithe offering.

[N.B.: Please note how consistently and ignorantly the Roman apologist omits this fact. The reader is invited to perform this simple demonstration: conduct an online search for the phrase, “see how contrary their opinions are to the mind of God”. Every Roman Catholic online ministry cites this letter, but none include that critical contextualizing phrase about feeding the poor.]

Now, let us reconstruct Ignatius’ liturgy from his own mouth.

As regarding the Dismissal, he says the heretics abstain from the Eucharist and Prayer. Of course they do. Unbelievers were not allowed to stay for it.

Having just mentioned the feeding of the poor, we know the Eucharist and prayer he just mentioned is the tithe offering and prayers of gratitude.

Also, we understand that the ancient consecration was performed by “confessing” the bread to be “My body.” But given Ignatius’ preference for “flesh” rather than “body,” and his propensity to expand upon a reference to Jesus, to include His passion, death and resurrection, Ignatius’ consecration would not merely have been to “confess” that “this is My body” but rather to “confess” that the bread “is the flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ, which suffered for our sins, and which the Father, of His goodness, raised up again.” (Smyrnæans, 7). That was Ignatius’ consecration.

When Ignatius is thus understood, we see the very same liturgical order in Ignatius as we do in the first three centuries of Christianity:

Dismissal: “they abstain… ” because they are not believers (To the Smyrnæans, 7)

Eucharist as an Offering: “… from the Eucharist and from prayer” which is comprised of first-fruits which are offered as an oblation “for the widow, or the orphan, or the oppressed; of the bond, or of the free; of the hungry, or of the thirsty,” to which Ignatius refers as a “love-feast” (To the Smyrnæans, 6, 7, 8)

Eucharist as the Supper: taking the unconsecrated Eucharistic bread in hand, the minister will then “confess that the Eucharist is the flesh [body] of our Savior Jesus Christ, flesh that suffered for our sins and that the Father, in his goodness, raised up again” (To the Smyrnæans, 7).

Clearly, Ignatius did not “confess” transubstantiated bread to be “the flesh of Christ.” Rather, he took unconsecrated bread from the Eucharist, and “confessed it to be Christ’s flesh” — in order to consecrate it. That was his mode of consecration. Just as no one would claim that Jesus “confessed” that the loaf and cup were consecrated, neither can we say that Ignatius “confessed” that the bread and wine had already become Jesus’ body and blood. Rather, he had simply consecrated it by “confessing” Jesus’ words over them.

Had Ignatius truly believed the Eucharist offering is where Jesus’ passion, death and resurrection was regularly exhibited, he would have directed Polycarp’s young congregation to avoid the heretics and instead seek proof of Jesus’ death and resurrection in the living flesh of Christ in the Eucharist that they worshiped. But he did not. It was to the Scriptures, not to the Supper, that the Smyrnæans were to turn for proof of Jesus’ actual flesh and spirit and passion and resurrection:

It is fitting, therefore, that you should keep aloof from such persons, and not to speak of them either in private or in public, but to give heed to the prophets, and above all, to the Gospel, in which the passion [of Christ] has been revealed to us, and the resurrection has been fully proved. But avoid all divisions, as the beginning of evils. (To the Smyrnæans, 7)

What is so remarkable about the Roman Catholic claim about the “Real Presence” in Ignatius is that we can easily prove contextually that every reference to the Eucharist in his letter was a reference to unconsecrated bread! “They abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer” referred to their failure to participate in the unconsecrated tithe offering. “They do not confess that the Eucharist is the flesh of our Savior Jesus Christ” simply means that they do not consecrate the unconsecrated bread. And Ignatius’ last reference to the Eucharist in the the letter to the Smyrnæans was simply a reference to the unconsecrated Eucharistic “love-feast” for the poor, which preceded the consecration and the Supper:

Let that be deemed a proper Eucharist, which is [administered] either by the bishop, … It is not lawful without the bishop either to baptize or to celebrate a love-feast; (To the Smyrnæans, 8)

Not once does Ignatius suggest that “the Eucharist” refers to bread that has already been consecrated.

Mr. Charles’ Anachronism

Let us now return to Mr. Charles’ two claims: that Ignatius “profoundly” taught “point by point” the Roman Catholic doctrines of the Sacrifice of the Eucharist and the Real Presence of Christ. Regarding the former, we can heartily agree that the Eucharistic sacrifice of the early church was the tithe offering “for the widow, or the orphan, or the oppressed; … the hungry, [and] the thirsty” to which Ignatius plainly attests when Mr. Charles is not redacting the evidence from his citations. But Ignatius’ Eucharistic offering was not the Roman Catholic Sacrifice of Jesus’ body and blood.

Regarding the latter, we merely point out that not one of Ignatius’ references to the Eucharist in the letter to the Smyrnæans was a reference to consecrated bread, and therefore Mr. Charles’ citations rather undermine his position than support it. The “Eucharist and prayer” from which the heretics abstained was the unconsecrated offering and love-feast for the poor. Ignatius’ “confession” that the Eucharist is “the flesh of Jesus Christ” was simply his liturgical consecration spoken over the unconsecrated Eucharist. It was not a confession that the bread had already been transubstantiated.

Of Mr. Charles’ citation from Ignatius’ letter to the Romans — “I desire the bread of God, which is the flesh of Jesus Christ … and for drink I desire his blood,” — we simply point out that Ignatius has here alluded to John 6, in which Jesus introduces the narrative (John 6:27) by appealing to Isaiah 55:1-4 in which the listener is implored to “eat” and “drink” the spoken and written words of God. Peter’s response to all this was not “Lord, to whom shall we go? thou hast the flesh and blood of eternal life” but rather, “Lord, to whom shall we go? thou hast the words of eternal life” (John 6:68). About Ignatius’ metaphorical flourish and Jesus’ appeal to Isaiah, we have expounded elsewhere, which the reader may explore further through the links provided. But Ignatius’ desire for the flesh and blood of Christ is the same desire that leads the Protestant to eat and drink of God’s word — the context in which Christ commanded us to eat of His flesh and blood (John 6).

As for Mr. Charles’ citation of Ignatius’ letter to the Philadelphians, we have herein identified the Scriptural passage to which Ignatius alluded — 1 Corinthians 10:16-17 — as well as Ignatius’ reticence to use the word “body” in reference to Christ. As such, Ignatius’ words, “have but one Eucharist. For there is one flesh of our Lord Jesus Christ” bear the same semantic weight as “have but one Eucharist. For there is one body of our Lord Jesus Christ,” an appeal to the unity of the Church exhibited in the communal meal to which Paul refers in that passage: a Eucharistic love-feast prior to the Lord’s Supper. As noted above, Tertullian relates that the “love-feast” prior to the Supper was to “benefit the needy” (Apology, 39), and “the Eucharist [is] to be eaten at meal-times” (De Corona, 3). Even the Catholic dictionary concedes that Eucharistic love-feasts “were often joined with the Eucharistic liturgy but in time were separated from the Mass because of the disorder and scandal they provoked.” Ignatius was not saying there should be “one Eucharist” because that Eucharist is Christ’s flesh. He was saying, as Paul had before him, that the unconsecrated communal Eucharistic agape meal ought to be orderly because “For we being many are one bread, and one body” (1 Corinthians 10:17). Or, adding Ignatius’ anti-Gnostic flare, “there is one flesh of our Lord Jesus Christ, and … one altar”. Of course there is. We, being one body of Christ, gather in unity to place on the altar the only sacrifice Malachi 1:11 envisioned: the ancient, and very Protestant, Eucharistic offertory.

The reason Mr. Charles believed any of his citations from Ignatius supported Roman Catholic doctrinal “points” is because he made a mistake that is endemic to all of Roman Catholic history and liturgiology — he interpreted the ancient Ignatius through the lens of the late fourth century novelty. Whereas Paul had placed the “Amen” immediately after the Eucharist as a communal affirmation of thanksgiving to God prior to the Consecration (1 Corinthians 14:16), the late 4th century saw a shift in which the Consecration was moved before the Eucharist, and the “Amen” became an affirmation of the offering of the body and blood of Christ.

Cyril of Jerusalem (350 A.D.) instructed the catechumen, on the day of his baptism, to “receive the Body of Christ, saying over it, Amen” (Catechetical Lectures 23 21). So, too, with the Apostolic Constitutions and Ambrose of Milan :

And let the bishop give the oblation, saying, The body of Christ; and let him that receives say, Amen. And let the deacon take the cup; and when he gives it, say, The blood of Christ, the cup of life; and let him that drinks say, Amen. (Apostolic Constitutions VIII 13 [c. 375 A.D.])

The Lord Jesus Himself proclaims: “This is My Body.” Before the blessing of the heavenly words [consecration] another nature is spoken of, after the consecration the Body is signified. He Himself speaks of His Blood. Before the consecration it has another name, after it is called Blood. And you say, Amen, that is, It is true. (On the Mysteries54 (c. 387 AD))

Augustine (c. 405), too, explained, “When you hear ‘The body of Christ,’ you reply ‘Amen’” (Sermon 272), for “the responsive Amen of those who believe in Him … is the voice of Christ’s blood” (Contra Faustum, XII.10). But it was not that way at the time of Ignatius, which Mr. Charles would know, if he were truly “deep in history.”

We will leave our readers with a deliciously ironic social reference to the Eucharist. In 2017, Canadian-American actor, Jim Carrey, for all of his ignorance, nevertheless came closer to the ancient meaning of the Eucharist than Roman Catholicism has in its 1600 years of existence. Speaking at a food kitchen for the poor, Mr. Carrey said,

When you make a loaf of bread in this kitchen, that is a Eucharist. You are blessing people with your work. You’re serving the world with your work, with your effort. That is a Eucharist. That is the body of Christ. (beginning at the 7:00 minute mark)

His statement, imperfect though it may be, stands closer to apostolic truth than all of Rome’s abominable liturgical sacrifices since the late fourth century. As proof, just read Hebrews 13:16 and Philippians 4:18 in which we are taught that our Eucharistic sacrifice is to “do good” and provide for those in need. Or read Paul’s Eucharistic teachings in 1 Corinthians 10, 11, 12 and 14, and what the ancient Church really thought the Eucharist was. Read Irenæus who taught that the loaf of bread becomes the Eucharist the moment it is “summoned” by the Lord as a tithe, and how Ignatius thought the purpose of the Eucharist was to care for the poor, and Athanasius’ admonition that we “take up our sacrifices, observing distribution to the poor.” We do not know what that kitchen staff believed about the Gospel, but we can affirm that the early church was willing to characterize the Eucharist in the same way Carrey did. His statement could have been more incisive, and could have more effectively drawn out the nuances of Pauline eucharistology and the carnal divisions of the Corinthian church. But it was not formally incorrect.

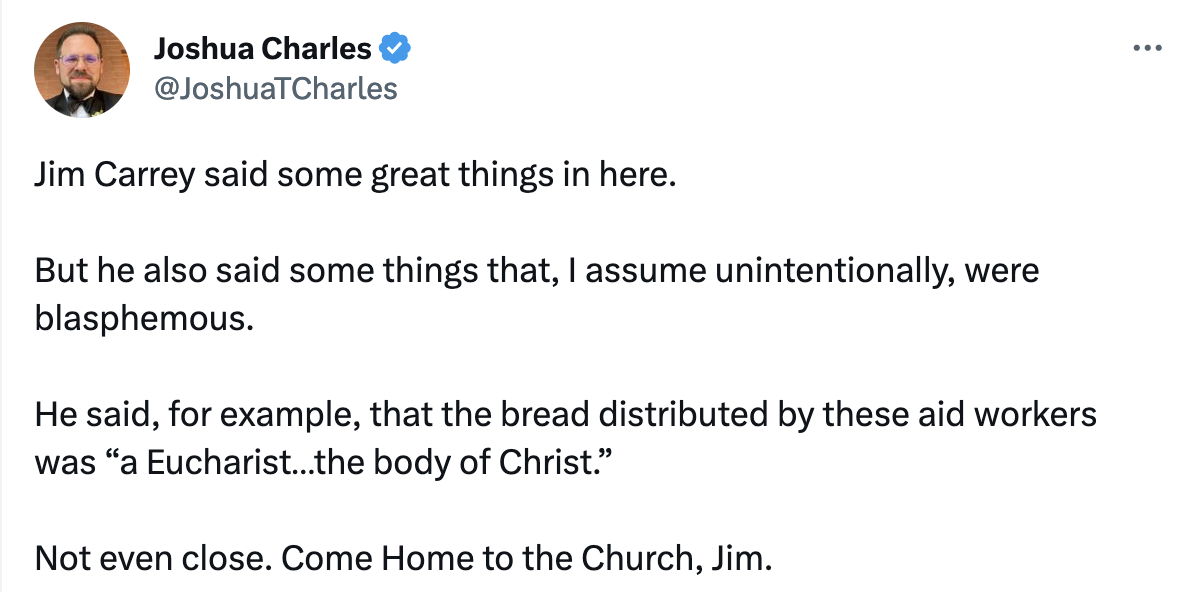

As we have noted elsewhere, the shame and scourge of Roman apologetics is to laud as “Apostolic tradition” what is not, and to scorn and abhor what is. Mr. Charles does not disappoint. He complained last week that Jim Carrey’s reference to the Eucharist was “blasphemous” and “not even close” to the true Eucharist of the ancient Church:

“He said, for example, that the bread distributed by these aid workers was ‘a Eucharist…the body of Christ.’

“He said, for example, that the bread distributed by these aid workers was ‘a Eucharist…the body of Christ.’

Not even close. Come Home to the Church, Jim.”

It is closer than you think, Joshua. Closer than you think.

We will pick up next time with another of Mr. Charles’ “points” of Roman Catholic doctrine from Ignatius.

Follow

Follow

Leave it up to antichrist to interpret sacrifice of dismissal ( missa) as sacrifice of Jesus for sins. If i understood your article correctly the dismissal of the newbies and backsliders and the sacrifice which was the tithe reffered to as the missa, Rome turned into a a sacrifice of Christ again. Im reminded of Galatians 5:1-4 Paul having to adresss those who wanted to be accepted by law in some way. He said they were severed from Christ and fallen from grace., This is so serious, as in Mat. 7 God will spit out tbose who plead their own works ( RC mass). We should all listen to Anselm who said when we stand at judgement we should only plead Christ and his righteousness. Well comstructed article. I enjoyed it k

Tim, kind of a random question, if you’re up for it: Are you aware of any Marian apparitions that played a direct role in either the Crusades or the persecution of Protestants?

None actually come to mind at the moment. The apparitions tend to focus on the need to worship the Eucharist and follow the pope. There are plenty of examples of indirect influence on the persecution, but they rarely address the protestant faith directly. Some of the most violent and dedicated counter-reformation mystics had encounters with “Mary,” but “she” seems to have just made them feel more confident in their counter-reformation.

I’m shocked by the depth of this article, I’ve never seen anything like this about Ignatius among Protestants.

Jose,

Most modern Protestants don’t read primary sources. If they did, you’d see more things like this.

That said, you should also read what Tim wrote here.

From c.450AD until 1743, only Latin copies of Irenaeus’ “Against Heresies” were known. Then, a Greek manuscript was found. This posed revolutionary, for it exposed that Irenaeus’ original Eucharist had been forged by the hand of a scribe into something else entirely. For more than a millennium, the Roman Catholic Church was in error, and it was burning people to death for it, as it did Dr. Hugh Latimer.

The thing is, the Protestants in the 1500s and 1600s knew that what the Roman Catholic church was teaching was a lie, even though it didn’t yet possess that piece of evidence to prove it.

How could they have known what the truth was even though the primary documents (at the time) explicitly contradicted the Protestant position? The answer to that question exposes Roman Catholicism for what it is.

Do not be surprised when you see something like this that you’ve never seen before. Much truth has been hidden and falsehood promoted in its place. But the truth has always been there for those who choose to see it. Men like Dr. Hugh Latimer reasoned with their minds and landed on the truth, even though they would not be vindicated until after their deaths.

Peace,

DR