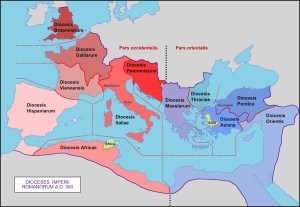

Over the last few weeks we have addressed the matter of the four kingdoms that arose out of Greece after Alexander’s death in 323 B.C.. As we described in Reduction of the Diadochi, The Bounds of their Habitation, and The Shifting Frame, Asia Minor and Thrace together comprised the Northern Kingdom; Syria, Babylon and beyond, the Eastern. Yet even though the commentaries at Daniel 8:8 and 11:4 almost universally agree that Asia Minor with Thrace comprised the Northern Kingdom in an Alexandrian Frame of Reference, the commentaries just as universally shift to a Judæan Frame at Daniel 11:5. In that shifted frame of reference the “King of the North” in 11:6 is presumed to refer to Syria, which only two verses earlier had been part of the Eastern Kingdom. No explanation is given for this change of reference except that it appears to make sense of the chapter, and further that the tradition of the shifting frame is to be received as authoritative for its antiquity. It is, after all, an ancient tradition. Continue reading …and South was South

Follow

Follow