Protestants who interact with Roman Catholics in any capacity are often surprised to find that they believe Mary is the Ark of the New Covenant. As Pope Pius XII explained in Munificentissiumus Deus in 1950—his “infallible” proclamation that Mary was assumed bodily into heaven—many Church Fathers have understood the Ark of the Covenant “as a type of the most pure body of the Virgin Mary” (Munificentissiumus Deus, 26). Thus, David’s exclamation, “Arise, O LORD, into thy rest; thou, and the ark of thy strength” (Psalm 132:8), is taken to prefigure Mary’s bodily assumption into Heaven (Munificentissiumus Deus, 29). Catholic Answers explains in an article by Steve Ray that the Woman of Revelation 12:1 is Mary, and because John saw the ark of the testimony in the heavenly temple in the preceding verse (Revelation 11:19), it must mean that Mary is the Ark of the New Covenant (Catholic Answers, Mary, Ark of the New Covenant). Steve Ray, former Protestant and now Roman Catholic apologist, tells us not to worry about the novelty of this Roman Catholic teaching on Mary. After all, he says, it is an apostolic teaching from the earliest days of Christianity:

“The understanding of Mary as the Ark of the New Covenant is nothing new. It was taught and celebrated early in Christian history.” (Steve Ray, Ark of the New Covenant -Quotes from the Fathers).

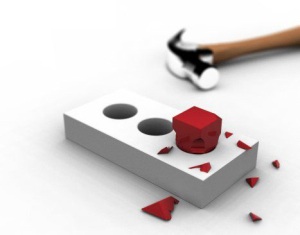

The problem with Steve Ray’s claim is a familiar one: the teaching and celebration of Mary as the Ark of the New Covenant originated in the latter part of the 4th century, and there is no evidence that it was proposed, believed or celebrated any earlier than that. “Mary as the Ark of the New Covenant” is something new indeed. Continue reading Searching for the Lost Ark

Follow

Follow