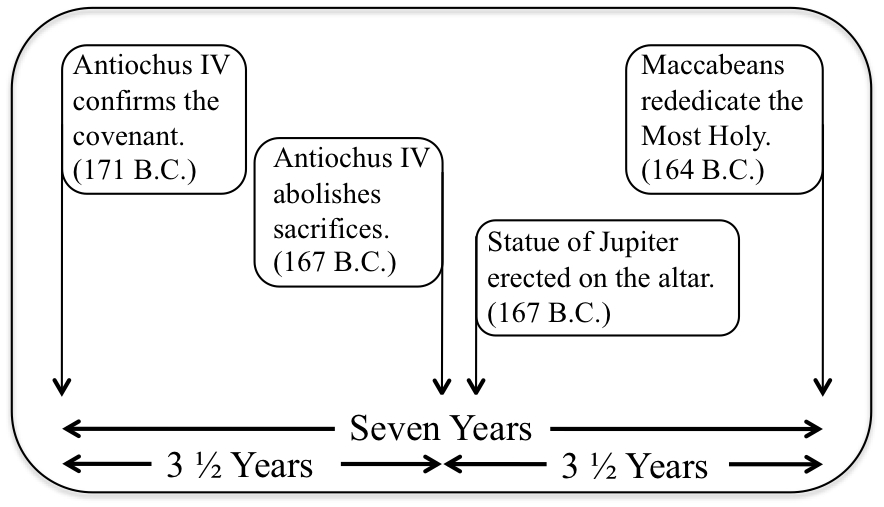

Last week, we began a discussion on the date of authorship of the book of Revelation, highlighting the angel’s discussion with John regarding the “scarlet coloured beast … having seven heads and ten horns” (Revelation 17:3). That seven-headed, ten-horned beast is a figure used repeatedly in Revelation (Revelation 12:3, 13:1, 17:3), and shows the significant symbolic unity the book shares with Daniel’s prophecies in Daniel 7. The Four Beasts of Daniel 7 together have seven heads and ten horns (1 Lion Head, 1 Bear Head, 4 Leopard Heads, 1 Beast Head with 10 horns upon it). Whatever the differences that exist between the “red dragon” (Revelation 12:3), sea beast (Revelation 13:1) and the “scarlet coloured beast” (Revelation 17:3), they are unified in their symbolic relationship to Daniel 7. Because the beasts of Daniel 7 share a strong chronological unity with Gold, Silver, Brass and Iron kingdoms of Daniel 2, we can also draw on that chronological unity to understand the date of John’s vision. Continue reading Legs of Iron, part 2

Follow

Follow